The End of Devil Hawker: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 15:17, 18 January 2020

The End of Devil Hawker is a short story written by Arthur Conan Doyle first published in The Saturday Evening Post on 23 august 1930.

Editions

- in The Saturday Evening Post (23 august 1930 [US]) 3 illustrations by Orison MacPherson

- in The Strand Magazine (november 1930 [UK]) 5 ill. by F. E. Hiley

Illustrations

- Illustrations by Orison MacPherson in The Saturday Evening Post (23 august 1930)

-

There is a full-length coloured print which shows him to be tall and magnificently proportioned, with broad shoulders, slim waist, clad in a tightly-buttoned green coat, buckskin breeches and high Hessian boots.

-

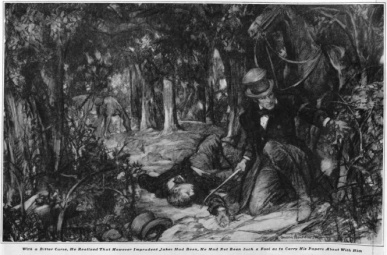

With a bitter curse, he realised that however imprudent Jakes had been, he had not been such a fool as to carry his papers about with him.

-

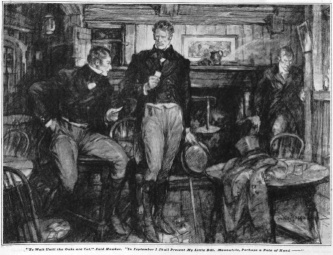

"To wait until the oaks are cut," said Hawker. "In September I shall present my little bill. Meanwhile, perhaps a note of hand—"

- Illustrations by F. E. Hiley in The Strand Magazine (november 1930)

-

With a bitter curse, he realised that however imprudent Jakes had been, he had not been such a fool as to carry his papers about with him.

-

-

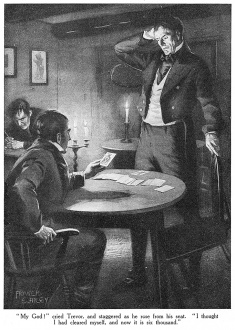

"My God!" cried Trevor, and staggered as he rose from his seat. "I thought I had cleared myself, and now it is six thousand."

-

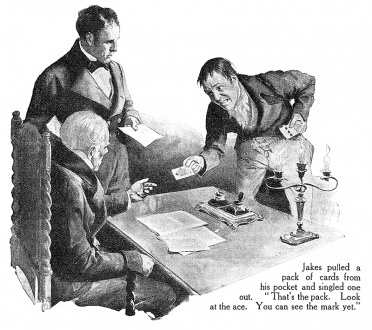

Jakes pulled a pack of cards from his pocket and singled one out. "That's the pack. Look at the ace. You can see the mark yet."

-

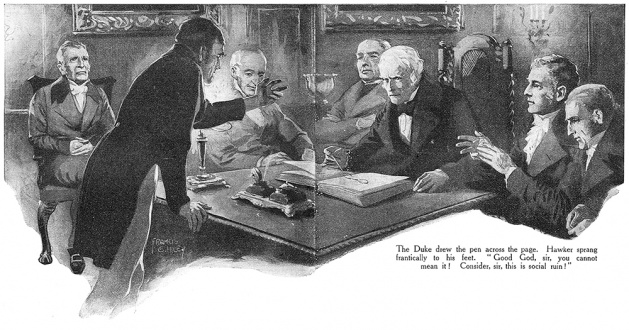

The Duke drew the pen across the page. Hawker sprang frantically to his feet. "Good Go, sir, you cannot mean it! Consider, sir, this is social ruin!"

The End of Devil Hawker

I

There is a fascinating little print shop around the comer of Drury Lane. When you pass through the old oaken doorway and into the dim dusty interior, you seem to have wandered into some corridor leading back through time, for on every side of you are the pictures of the past. But very specially I value that table on the left where lies the great pile of portrait prints heaped up in some sort of order of date: There you see the pictures of the men who stood round the throne of the young Victoria, of Melbourne, of Peel, of Wellington, and then you come on the D'Orsay and Lady Blessington period, and the long and wonderful series of H.B., the great, unknown John Doyle, who, in his day, was a real power in the land. Farther back still you come on the bucks and prize fighters of the Regency — the pompous Jackson, the sturdy Cribb, the empty Brummel, the chubby Alvanley. And then you may chance upon a face which you cannot pass without a second and a longer look. It is a face which Mephistopheles might have owned; thin, dark, keen, with bushy brows and fierce, alert eyes which glare out from beneath them. There is a full-length coloured print which shows him to be tall and magnificently proportioned, with broad shoulders, slim waist, clad in a tightly-buttoned green coat, buckskin breeches and high Hessian boots. Below is the inscription: "Sir John Hawker" — and that is the Devil Hawker of the legends.

In his short but vivid career, the end cf which is here outlined, Hawker was the bully of the town. The bravest shrank away from the angry, insolent glare of those baleful eyes. He was a famous swordsman and a remarkable pistol shot — so remarkable that three times he starred the kneecap of his man; the most painful injury which he could inflict. But above all, he was the best amateur boxer of his day, and had he taken to the ring it is likely that be would have made a name. His hitting is said to have been the most ferocious ever seen, and it was his amusement to try out novices at Cribb's rooms, which were his favorite haunt, and to teach them how to stand punishment. It gratified his pride to show his skill, and his cruel nature to administer pain to others. It was in these very rooms of Cribb that this little sketch of those days opens, where, as on a marionette stage, I would try to show you what manner of place it was and what manner of people walked London in those full·blooded, brutal and virile old days.

First as to the place. It is at the corner of Panton Street, and you see over a broad, red-curtained door the sign, "Thomas Cribb. Dealer in Liquor and Tobacco," with "The Union Arms" printed above. The door leads into a tiled passage which opens on the left into a common bar behind which save on special evenings, a big, bull·faced, honest John Bull of a man may be seen with two assistants of the sparring-partner type, handing out refreshment and imbibing gratis a great deal more than was good for their athletic figures. Already Tom is getting a waistline which will cause his trainer and himself many a weary day at his next battle: if , indeed, the brave old fellow has not already come to the last or his fights, when he defended the honor or England by breaking the cast-iron jaw of Molyneaux, the black.

If, instead of turning into the common bar, you continue down the passage, you find a green-baize door with the word "Parlour" printed across one upper panel of glass. Push it open and you are in a room which is spacious and comfortable. There is sawdust on the floor, numerous wooden armchairs, round tables for the card players, a small bar presided over by Miss Lucy Stagg, a lady who had been accused of many things, but never of shyness, in the corner, and a fine collection of sporting pictures round the walls. At the back were swing doors with the words "Boxing Saloon" printed across them, leading into a large bare apartment, with a roped ring in the centre, and many pairs of gloves hanging upon the wall, belonging, for the most part, to the Corinthians who came up to have lessons from the champion, whose classes were only exceeded by those of Gentleman Jackson in Bond Street.

It was early in the particular evening of which I speak, and there was no one in the parlour save Cribb himself, who expected the quality that night, and was cleaning up in anticipation. Lucy wiped glasses languidly in her little bar. Beside the entrance door was a small, shriveled weasel of a man, Billy Jakes by name, who sat behind a green-baize table, in receipt of custom as a bookmaker, dog-fancier or cock supplier — a privilege for which he paid Tom a good round sum every year. As no customers had appeared, he wandered over to the little bar.

"Well, things are quiet tonight, Lucy."

She looked up from polishing her glasses.

"I expect they will be more lively soon, Mr. Jakes. It is full early."

"Well, Lucy, you look very pretty tonight. I expect I shall have to marry you yet."

"La, Mr. Jakes, how you do carry on!"

"Tell me, Lucy; do you want to make some money?"

"Everyone wants that, Mr. Jakes."

"How much can you lay your hands on?"

"I dare say I could find fifty pounds at a pinch."

"Wouldn't you like to turn it into a hundred?"

"Why, of course I would."

"It's Saracesca for the Oaks. I'd give you two to one, which is better than I give the others. She's a cert it ever there is one."

"Well, if you say so, Mr. Jakes. The money is upstairs in my box. But if you can really turn it into—"

Fortunately, honest Tom Cribb had been within earshot of this little debate, and he now caught the man roughly by the sleeve and twirled him in the direction of his table.

"You dirty dog; doing the poor girl out of her hard-earned savings!"

"All right, Tom. Only a joke! Only Billy Jakes' little joke!... I wouldn't have let you lose. Lucy!"

"That's enough," said Tom. "Don't you heed him, Lucy. Keep your money in your box."

The green swing-door opened and a number of bucks, in black coats, brown coats, green coats and purple, came filing into the room. The shrill voice of Jakes was at once uplifted and his clamour filled the air.

"Now, my noble sportsmen," he cried, "back your opinions! There is a bag of gold waiting, and you have only to put your hands in. How about Woodstock for the Derby? How about Saracesca for the Oaks? Four to one! Four to one! Two to one, bar one!"

The Corinthians gathered for a moment round the bookie's table, for his patter amused them.

"Lots of time for that, Jakes," said Lord Rulton, a big bluff county magnate and landowner.

"But the odds are shorter every day. Now's your time, my noble gamesters! Now's the time to sow the seed! Gold to be had for the asking, waitin' there for you to pick up. I like to pay it. It pleases me to see happy faces round me. I like to see them smiling Now's your time."

"Why, half the field may scratch before the race," said Sir Charles Trevor — the imperturbable Charles, whose estate has been sucked dry by its owner's wild excesses.

"No race, no pay. The old firm gives every gamester a run for his money. The knowing ones are all on to it. Sir John Hawker has five hundred on Woodstock."

"Well, Devil Hawker knows what he is about," said Lord Annerley, a dashing young Corinthian.

"Have fifty on the filly for the Oaks, Lord Ruffton. Four to one?"

"Very good, Jakes," said the nobleman handing out a note. "I suppose I shall find you after the race."

"Sitting here at this table, my lord. Old established place of business. You've got a certainty, my lord."

"Well," said a young Corinthian, "if it is as certain as that, I'll have fifty too."

"Right, my noble sportsman I book it at three to one."

"I thought it was four."

"It was four. Now it is three. You't lucky to get before it is two. Will you take your winnings in paper or gold?"

"Well, in gold."

"Very good, sir. You'll find me waiting at this table with a bag of gold at ten by the clock on the day after the race. It will be in a green-baize bag with a grip, so you can easily carry it. By the way, I've got a fighting cock that's never been beat. Would any of you gentlemen—"

But the door ad swung open and Sir John Hawker's handsome figure and sinister face filled the gap. The others moved towards the small bar Hawker paused a moment at the bookie's table.

"Hullo, Jakes; doing some fool out of their money as usual?"

"Tut, tut, Sir John, you should know me by now."

"Know you, you rascal! You have had a cool two thousand out of me from first to last I know you too well."

"All you want is to persevere. You'll soon have it all back, Sir John."

"Hold your tongue, I say. I have had enough."

"No offense, my noble sportsman. But I have a brindled terrier down at the stable that's the best of rats in London."

"I wonder he hasn't had a nip at you then. Hullo, Tom."

Cribb had come forward as usual to greet his Corinthian guests.

"Good evening, Sir John. Going to put them on to-night?"

"Well, I'll see. What have you got?"

"Half a dozen up from old Bristol. That place is as full of milling coves as a bin is of bottles."

"I may try one of them over."

"Then play light. Sir John. You cracked the ribs of that lad from Lincoln. You broke his heart for fighting."

"It may as well be broke early as late. What's the use of him if he can't take punishment?"

Several more men had come into the room; one of them exceedingly drunk, another just a little less so. They were two of the Tom-and-Jerry clique who wandered day and night on the old round from the Haymarket to Panton Street and St. James, imagining that they were seeing life. The drunken one — a young hawbuck from the shires — was noisy and combative. His friend was trying to put some term to their adventures.

"Come, George," he coaxed, "we'll just have one drink here. Then one at the Dive and one at the Cellars, and wind up with broiled bones at Mother Simpson's."

The name of the dish started ideas in the drunken man's head. He staggered in the direction of the landlord. "Broiled bones!" he cried. "D'you hear? I want broiled bones! Fetch me dish — large dish — of broiled bones this instant — under pain — displeasure."

Cribb, who was well accustomed to such visitors, continued his conversation with Hawker without taking the slightest notice. They were discussing a possible opponent for old Tom Shelton, the navvy, when George broke in again.

"Where the devil's those broiled bones? Here, landlord! Ole Tom Cribb! Tom, give me large dish broiled bones this instant , or I punch your old head." As Cribb still took not the faintest heed, George became more bellicose.

"No broiled bones!" he cried. "Very good! Prepare defend yourself!"

"Don't hit him, George!" cried his more sober companion in alarm. "It's the champion."

"It's a lie. I am the champion. I'll give him smack in the chops. See if I don't."

For the first time Cribb turned a slow eye in his direction.

"No dancin' allowed here, sir," he said.

"I'm not dancing. I'm sparring."

"Well , don't do it, whatever it is."

"I'm going to fight you. Going to give old Tom a smack in the chops."

"Some other time, sir, I'm busy."

"Where're those bones? Last time of asking."

"What bones? What is he talkin' of?"

"Sorry, Tom, but have to give you good thrashing. Yes, Tom, very sorry, but must have lesson."

He made several wild strokcs in the air, quite out of distance, and finally fell upon his knees. His friend picked him up.

"What d'you want to be so foolish for, George?"

"I had him nearly beat."

Tom looked reproachfully at the soberer friend. "I am surprised at you, Mr. Trelawney."

"Couldn't help it, Tom. He would mix port and brandy."

"You must take him out."

"Come on, George; you've got to go out."

"Got to go! No, sir; round two, Come up smilin'. Time!"

Tom Cribb gave a sign and a stalwart potman threw the pugnacious George over his shoulder and carried him out of the room, kicking violently, while his friend walked behind. Cribb laughed.

"There's seldom an evening that I don't have that sort of nuisance."

"They would not do it twice to me," said Hawker. "I'd send him home, and his wench wouldn't know him."

"I haven't the heart to touch them. It pleases the poor things to say they have punched the champion of England."

The room had now begun to fill up. At one end a circle had formed round the bookie's table, On the other side there was a group at the small private bar where very broad chaff was being exchanged between some of the younger bucks and Lucy, who was well able to take care of herself. Cribb had gone inside the swing doors to prepare for the boxing, while Hawker wandered from group to group, leaving among these fearless men, hard-riding horsemen of the shires and dare-devils at every sport, a vague feeling of repulsion which showed itself in a somewhat formal response to his brief greetings. He paused at one chattering group and looked sardonically at a youth who stood somewhat apart listening to, but not joining in, the gay exchange of repartee. He was a well-built young man with a singularly beautiful head, crowned by a mass of auburn curls. His figure might have stood for Adonis, were it not that one foot was slightly drawn up, which caused him to wear a rather unsightly boot.

"Good evening, Hawker," said he.

"Good evening, Byron. Is this one of your hours of idleness?"

The allusion was to a book of verse which the young nobleman had just brought out, and which had been severely handled by the critics.

The poet seemed annoyed, for he was sensitive on the point.

"At least I cannot be accused of idleness today," said he. "I swam three miles downstream from Lambeth, and perhaps you have not done so much."

"Well done!" said Hawker. "I hear of you at Angelo's, and Jackson's, too. But fencing needs a quick foot. I 'd stick to the water if I were you." He glanced down at the malformed limb.

Byron's blue-gray eyes blazed with indignation.

"When I wish your advice as to my personal habits, Sir John Hawker, I will ask for it."

"No harm meant," said Hawker carelessly. "I am a blunt fellow and always say what I think."

Lord Rufton plucked at Byron's sleeve. "That's enough said," he whispered.

"Of course," added Hawker, "if anyone does not like my ways, they can always find me at White's Club or my lodgings in Charles Street."

Byron, who was utterly fearless, and ready, though he was still only a Cambridge undergraduate, to face any man in the world, was about to make some angry reply in spite of the well-meant warnings of Lord Rufton, when Tom Cribb came bustling in and interrupted the scene.

"All ready, my lords and gentlemen. The fighting men are in their place. Jack Scroggins and Ben Burn will begin."

The company began to move towards the door of the sparring saloon. As they filed in, Hawker advanced quietly and touched the reckless baronet, Sir Charles Trevor, upon the shoulder.

"I must have a word with you, Charles."

"I want to get a ringside seat, John."

"Never mind that. I must have a word."

The others passed in. Devil Hawker and Sir Charles had the room to themselves, save for Jakes, counting his money at his distant table, and the girl, Lucy, coming and going in her little alcove. Hawker led Sir Charles to a central seat.

"I have to speak to you, Charles, of that three thousand you owe me. It pains me vastly, but what am I to do? I have my own debts to settle, and it is no easy matter."

"I have the matter in hand, John."

"But it presses"

"I'll pay it all right. Give me time."

"What time?"

"We are cutting the oaks at Selincourt. They should all be down by the autumn. I can get an advance then that will clear all that I owe you."

"I don't want to press you, Charles. If you would like a sporting flutter to clear your debt, I'm ready to give It to you at once."

"What do you mean?"

"Well, double or quits. Six thousand or nothing. If you're not afraid to take a chance, I'll let you have one."

"Afraid, John. I don't like that word."

"You were always a brave gamester, Charles. Just as you like in the matter. But you might clear yourself with a turn of the card, while, on the other hand, if all the Selincourt timber is going, six thousand will be no more to you than three."

"Well, it's a sporting offer, John. You say the turn of a card. Do you mean one simple draw?"

"Why not? Sudden death. Win or lose. What say you?"

"I agree."

A pack of cards was lying on a near-by table. Hawker stretched out a long arm and picked them up.

"Will thee do?"

"By all means."

He spread them out with a sweep of his hand.

"Do you care to shuffle?"

"No, John. Take them as they are."

"Shall it be a single draw?"

"By all means."

"Will you lead?"

Sir Charles Trevor was a seasoned gambler, but never before had three thousand pounds hung upon the turn of a single card. But he was a reckless plunger, and roared with laughter as he turned up the queen of clubs.

"That should do you, John."

"Possibly," said Hawker, and turned the ace of spades.

"I thought I had cleared myself, and now it is six thousand," cried Trevor, and staggered as he rose from his seat.

"To wait until the oaks are cut," said Hawker. "In September I shall present my little bill. Meanwhile, perhaps a note of hand—"

"Do you doubt my word, John!"

"No, no, Charles, but business is business. Who knows what may happen? I'll have a note of hand."

"Very good. You'll have it by the post tomorrow. Well, I bear no grudge. The luck was yours. Shall we have a glass upon it?"

"You were always a brave loser, Charles." The two men walked together to the little bar in the corner.

Had either looked back he would have seen a sight which would have surprised him. During the whole incident the little bookmaker had sat absorbed over his accounts, but with a pair of piercing eyes glancing up every now and then at the two gamblers. Little of their talk had been audible from where he sat, but their actions had spoken for themselves. Now, with amazing, but furtive, speed he stole across, picked up one card from the table and hurried back to his perch, concealing it inside his coat. The two gentlemen, having taken their refreshment, turned toward the boxing saloon; Sir Charles disappearing through the swing-door, from behind which came the thud of heavy blows, the breathing of hard-spent men, and every now and then a murmur of admiration or of criticism.

Hawker was about to follow his companion when a thought struck him and he returned to the card table, gathering up the scattered cards. Suddenly he was aware that Jakes was at his elbow and that two very shrewd and malignant eyes were looking up into his own.

"Hadn't you best count them, my noble sportsman?"

"What d'you mean?" The Devil's great black brows were drawn down and his glance was like a rapier-thrust.

"If you count them you'll find one missing."

"Why are you grinning at me, you rascal?"

"One card missing, my noble sportsman. A good winning card, too — the ace of spades. A useful card, Sir John."

"Where is it, then?"

"Little Billy Jakes has It. It's here" — and he slapped his breast pocket. "A little playing card with the mark of a thumbnail on one corner of the back."

"You Infernal blackguard!"

Jakes was no coward , but he shrank away from that terrible face. "Hands off, my noble sportsman! Hands off, for your own sake! You can knock me about. That's easily done. But it won't end there. I've got the card. I could call back Sir Charles and fill this room in a jiffy. There would be an end of you, my beauty."

"It's all a lie — a lie."

"Right you are. Say so, if you like. Shall I call in the others, and you can prove it a lie? Shall I show the cards to Lord Rufton and the rest?"

Hawker's dark face was moving convulsively. His hands were twitching with his desire to break the back of this little weasel across his knee. With an effort, he mastered himself.

"Hold on, Jakes. We have always been great friends. What do you want? Speak low or the girl will hear."

"Now, that's talking. You got six thousand just now. I want half."

"You want three thousand pounds. What for?"

"You're a man of sense. You know what for. I've a tongue, and I can hold it if it's worth my while."

Hawker considered for a moment. "Well, suppose I agree."

"Then we can fix it so."

"Say no more. We will consider it as agreed."

He turned away, his mind full of plans by which he could gain time and disavow the whole business. But Jakes was not a man so easily fooled. Many people had found that to their cost.

"Hold on, my noble sportsman. Hold on an instant. Just a word of writing to settle it."

"You dog, is my word not enough?"

"No, Sir John, not by a long way... No, if you hit me I'll yell. Keep your hands off. I tell you I want your signature to it."

"Not a word."

"Very good then. It's finished." Jakes started for the door of the saloon.

"Hold hard! What am I to write?"

"I'll do the writing." He turned to the little alcove where Lucy, who was accustomed to every sort of wrangling and argument, was dozing among her bottles.

"Here, my dear; wake up! I want pen and ink."

"Yes, sir."

"And paper?"

"There is a billhead. Will that do? Dearie me, it's marked with wine!"

"Never mind; that will do."

Jakes seated himself at a table and scribbled while Hawker watched him with eyes of death. Jakes walked over to him with the scrawl completed. Hawker read it over in a low mutter:

"'In consideration of your silence—'" He paused and glared.

"Well, that's true, ain't it? You don't give me half for the love of William J akes, Esquire, do you now?"

"Curse you, Jakes! Curse you to hell!"

" Let it out my noble sportsman. Let it out or you'll bust. Curse me again. Then sign that paper."

"'The sum of three thousand pounds, to be paid on the date when there is a settlement between me and Sir Charles Trevor.' Well, give me the pen and have done. There! Now give me that card."

Jakes had thrust the signed paper into his inner pocket.

"Give me the card, I say!"

"When the money is paid, Sir John. That's only fair."

"You devil!"

"Can't find the right word, can you? It'll not been invented yet, I expect."

Jakes may have been very near his death at that moment. The furious passions of the bully had reached a point when even his fears of exposure could hardly hold him in check. But the saloon door had swung open and Cribb entered the room. He looked with surprise at the ill-assorted couple.

"Now, Mr. Jakes, time is up, you know. You've passed your hours."

"I know, Tom, but I had an important settling-up with Sir John Hawker. Had I not, Sir John?"

"You've missed the first bout, Sir John. Come and see Jack Randall take a novice."

Hawker took a last scowl at the book-maker and followed the champion into the saloon. Jakes gathered up his papers into his professional bag and went across to the little bar.

"A double brandy, my dear," said he to Lucy. "I've had a good evening, but it's been a bit of a strain upon my nerves."

II

IT WAS late in September that the grand old ancestral oaks of Selincourt were given over to the contractor, and that their owner, having at last a large balance at his bankers', was able to redeem the more pressing of his debts. It was only a day later that Sir John Hawker, with Sir Charles' note of hand for six thousand pounds in his pocket, found himself riding down the highroad at Six-Mile Bottom near Newmarket. His mount was a great black stallion as powerful and sinister as himself. He was brooding over his own rather precarious affairs, which involved every shilling which he could raise, when there was the click of hoofs beside him and there was Billy Jakes upon his well- known chestnut cob.

"Good evening, my noble sportsman," said he. "I was looking out for you at the stables, and when I saw you ride away, I thought it was time to come after you. I want my settlement, Sir John."

"What settlement? What are you talking of?"

"Your written promise to pay three thousand. I know you have had your money."

"I don' t know what you are talking about. Keep clear of me or you will get a cut or two from this hunting crop."

"Oh, that's the game, is it? We will see about that. Do you deny your signature upon this paper?"

"Have you the paper on you?"

"What's that to you?"

"It was not wise, Billy Jakes, to trust yourself alone upon a country road with one of the most dangerous men in England. For once your cupidity has been greater than your shrewdness."

A quick glance of those deadly, dark eyes to right and to left, and then the heavy hunting crop came down with a crash upon the bookmaker's head. With a cry, he dropped from the cob, and he had hardly reached the ground before the Devil had sprung from the saddle, and, with his left arm through his bridle rein to hold down his plunging horse, he was rapidly running his right hand through the pockets of the protrate man. With a bitter curse, he realised that however imprudent Jakes had been, he had not been such a fool as to carry his papers about with him.

Hawker rose, looked down at his half-conscious enemy, and then slowly drew his spur across his face. A moment later he had sprung into his saddle and was on his way London-wards, leaving the sprawling and bleeding figure in the dust of the highway. He laughed with exultation as he rode, for vengeance was sweet to him, and he seldom missed it. What could Jakes do? If he took him into the criminal courts, it was only such an assault as was common enough in those days of violence. If, on the other hand, he pursued the matter of the card and the agreement, it was an old story now, and who would take the word of the notorious bookmaker against that of one of the best-known men in London! Of course, it was a case of forgery and blackmail. Hawker looked down at his bloody spur and felt well content with his morning's work.

Jakes was raised to his feet by some kindly traveler and was brought back, half-conscious, to Newmarket. There, for three days, he kept his room and nursed both his injuries and his grievance. Upon the fourth day he reached London, and that night he made his way to the Albany and knocked at a door which bore upon a shining brass plate the name or Sir Charles Trevor.

It was the first Tuesday of the month, the day on which the committee of Watier's Club was wont to assemble. Half a dozen of them had sauntered into the great board-room, decorated with heavy canvases on the walla, and with highly polished dark mahogany furniture, which showed up richly against the huge expanse of red Kidderminster carpet. The Duke of Bridgewater, a splendid, rubicund old gentleman, grey-haired but virile, leaning heavily upon an amber-headed cane, came hobbling in and bowed affably to the waiting committee-men.

"How Is the gout, Your Grace?"

"A little sharp at times. But I can still get my foot into the stirrup. Well, well , I suppose we had better get to work." He took his seat in the centre of a half-moon table at one end of the room. Raising his quizzing-glass he looked round him.

"Where is Lord Foley?"

"He is racng, Sir. He will not he here."

"The dog! He takes his duties too lightly. I would rather be on the heath myself."

"I expect we all would."

"Ah, is that you, Lord Rufton?... How are you, Colonel D'Acre!... Bunbury, Scott, Poyntz, Vandeleur, good-day to you! Where is Sir Charles Trevor?"

"He is in the members' room," said Lord Rufton. "He said he would wait Your Grace's pleasure. The fact is that he has a personal interest in a case which comes before us, and he thought he should not have a hand in judging it."

"Ah, very delicate! Very delicate indeed!" The Duke had taken up the agenda paper and stared at it through his glass. "Dear me, dear me! A member accused of cheating at cards! And Sir John Hawker too! One of the best-known men in the club. Too bad! Too bad! Who is the accuser?"

"A bookmaker named Jakes, Your Grace!"

"I know him. Has a stand at Tom Cribb's. A rascal if ever I saw one. However, we must look into it. Who has the matter in hand?"

"I have been asked to attend to it," said Lord Rufton.

"I am not lure," said the Duke, "that we are right in taking notice of what such a fellow says about a member of this club. Surely, the law courts are open."

"I entirely agree with Your Grace," said a solemn man upon the Duke's left. He was General Scott, who was said to live on toast and water, and win ten thousand a year from his more sober companions.

"I would point out to you, sir, that the alleged cheating was at the expense of Sir Charles Trevor, a member of the club. It was not Sir Charles, however, who moved in the matter. There was a violent quarrel between the man Jakes and Sir John Hawker, and this is the result."

"Then the bookmaker has brought the case before us for revenge," said the Duke. "We must move carefully in this matter. I think we had best see Sir Charles first. Call Sir Charles."

The tall red-plushed footman at the door disappeared. A moment later, Sir Charles, debonair and smiling, stood before the committee.

"Good day, Sir Charles," said the Duke. "This is a very painful business."

"Very, Your Grace."

"I understand from what is on the agenda paper that on May third, of this year, you met Sir John at Cribb's Parlour and you cut cards with him at three thousand pounds a cut."

"A single cut, Your Grace."

"And you lost?"

"Unfortunately."

"Well, now, did you in any way suspect foul play at the time?"

"Not in the least."

"Then you have no charge against Sir John!"

"None on my own behalf. Other people have something to say."

"Well, we can listen to them in their turn. Won' t you take a chair, Sir Charles? Even if you do not vote, there can be no objection to your presence. Is Sir John in attendance?"

"Yes, Sir."

"And the witness?"

"Yes, Sir."

"Well, gentlemen, it is clearly a very serious matter, and I understand that Sir John is a difficult person to deal with. However, we can make no exceptions, and we are numerous enough and have, I trust, sufficient social weight to carry this affair to a conclusion." He rang for the footman.

"Place a chair in the centre, please! Now tell Sir John Hawker the committee would be honoured if he would step this way."

A moment later the formidable face and figure of the Devil had appeared at the door. With a scowl at the members present, he strode forward, bowed to the Duke, and seated himself opposite the semicircle formed by the committee.

"In the first place, Sir John," said the Duke, "you will allow me to express my regret and that of your fellow members that it should be our unpleasant duty to ask you to appear before us. No doubt the matter will prove to be a mere misunderstanding, but we felt that it was due to your own reputation as well as to that of the club that no time should be lost In setting the matter right."

"Your Grace," said Hawker, leaning forward and emphasising his remarks with his clenched hand, "I protest strongly against these proceedings. I have come here because it shall never be said that I was shy of meeting any charge, however preposterous. But I would put it to you, gentlemen, that no man's reputation is safe if the committee of his club is prepared to take up any vague slander that may circulate against him."

"Kindly read the terms of the charge, Lord Rufton."

"The assertion is," he read, "that at ten o'clock on the night of Thursday, May third, in the parlour of Tom Cribb's house, the Union Arms, Sir John Hawker did, by means of marked cards, win money from Sir Charles Trevor, both being members of Watier's Club."

Hawker sprang from his chair. "It is a lie — a damned lie!" he cried.

The Duke held up a deprecating hand. "No doubt — no doubt. I think, however, Sir John, that you can hardly describe it as a vague slander."

"It is monstrous! What is to prevent such a charge being leveled at Your Grace? How would you like, sir, to be dragged up before your fellow members?"

"Excuse me, Sir John," said the Duke urbanely. "The question at present is not what might be preferred against me, but what actually is preferred against you. You will, I am sure, appreciate the distinction. What do you propose, Lord Rufton?"

"It is my unpleasant duty, Sir John," said Lord Rufton, "to array the evidence before the committee. You will , I am sure, acquit me of any personal feeling in the matter."

"I look on you, sir, as a damned mischievous busybody."

The Duke put up his pudgy many-ringed hand in protest.

"I am afraid, Sir John, that I must ask you to be more guarded in your language. To me, it is immaterial, but I happen to know that General Scott has an objection to swearing. Lord Rufton is merely doing his duty in presenting the case."

Hawker shrugged his broad shoulders.

"I protest against the whole proceedings," he said.

"Your protest will be duly entered in the minutes. We have heard, before you entered, the evidence of Sir Charles Trevor. He has no personal complaint. So far as I can see, there is no case."

"Ha! Your Grace is a man of sense. Was ever an indignity put upon a man or honor on so small a pretext?"

"There is further evidence, Your Grace," said Lord Rufton. "I will call Mr. William Jakes."

At a summons the gorgeous footman swung open the massive door and Jakes was ushered in. It was a month or more since the assault, but the spur mark still shone red across his sallow cheek. He held hie cloth cap in his hand, and rounded his back as a tribute to the oompany, but his cunning little eyes, from under their ginger lashes, twinkled knowingly, not to say impudently, as ever.

"You are William Jakes, the bookmaker? " said the Duke.

"The greatest rascal in London," interpolated Hawker.

"There is one greater within three yards of me," the little man snarled. Then, turning to the Duke: "I'm William Jakes, Your Worship, known as Billy Jakes at Tattersall's. If you want to back a horse, Your Worship, or care to buy a game-cock or a ratter, you'll get the best price—"

"Silence, sir," said Lord Rufton. "Advance to this chair."

"Certainly, my noble sportsman."

"Don't sit. Stand beside it."

"At your service, gentlemen."

"Shall I cross-examine, Your Grace?"

"I understand, Jakes, that you were In Cribb's back parlour on the night of May third of this year?"

"Lord bless you, Sir, I 'm there every night. It's where I meet my noble Corinthians."

"It is a sporting house, I understand."

"Well, my lord, I can't teach you much about it." There was a titter from the committee, and the Duke broke in.

"I dare say we have all enjoyed Tom's hospitality at one time or another," he said.

"Yes, indeed, Your Grace. Well I remember the night when you danced on the crossed 'baccy pipes."

"Keep your witness to the point," said the smiling Duke.

"Tell us now what you saw pass between Sir John Hawker and Sir Charles Trevor."

"I saw all there was to see. You can trust little Billy Jakes for that. There was to be a cutting game. Sir John reached out for the cards, which lay on another table. I had seen him look over those cards in advance and turn the end of one or two with his thumb nail."

"You liar!" cried Sir John.

"It's an easy trick to mark them so that none can see. I've done — I know another man that can do it. You must keep your right thumb nail long and sharp. Well, look at Sir John's now."

Hawker sprang from his chair. "Your Grace, am I to be exposed to these insults?"

"Sit down, Sir John. Your indignation is most natural. I suppose it is not a fact that your right thumbnail—"

"Certainly not!"

"Ask to see!" cried Jakes.

"Perhaps you would not mind showing your nail?"

"I will do nothing of the kind."

"Of course you are quite within your rights in refusing — quite," said the Duke. "Whether your refusal might in any way prejudice your case is a point which you have no doubt considered... Pray continue, Jakes."

"Well, they cut and Sir John won. When be turned his back, I got the winning card, and saw that it was marked. I showed it to Sir John when we were alone."

"What did he say?"

"Well, my lord, I wouldn't like to repeat before such select company as this some of the things he laid. He carried on shocking. But after a bit he saw the game was up and he consented to my having half shares."

"Then," said the Duke, "you became, by your own admission, the compounder of a felony."

Jakes gave a comical grimace.

"No breaks here! This ain't a court, is it? Just a private house, as one might say, with one gentleman chatting easy like with other ones. Well, then, that's just what I did do."

The Duke shrugged hie shoulders. "Really, Lord Rufton, I do not see how we can attach any importance to the word of such a witness. On his own confession he is a perfect rascal."

"Your Grace, I'm surprised at you!"

"I would not condemn any man — far less the member of an honorable club — on this man's word."

"I quite agree. Your Grace," said Rufton. "There are, however, some corroborative documents."

"Yes, my noble sportsmen," cried Jake in a sort of ecstasy, "there's lots more to come. Billy's got a bit up his sleeve for a finish. How's that?" He pulled a pack of cards from his pocket and singled one out. "That's the pack. Look at the ace. You can see the mark yet."

The Duke examined the card. "There is certainly a mark," he said, "which might well be made by a sharpened nail."

Sir John was up once more, his face dark with wrath.

" Really, gentlemen, there should be some limit to this foolery. Of course these are the cards. Is it not obvious that after Sir Charles and I had left, this fellow gathered them up and marked them so as to put forward a blackmailing demand? I only — I only wonder that he has not forged some document to prove that I admitted this monstrous charge."

Jakes threw up his hands in admiration.

"By George, you have a nerve! I always said it. Give me Devil Hawker for nerve. Grasp the nettle, eh? Here's the document he talks about." He handed a paper to Lord Rufton.

"Would you be pleased to read it?" said the Duke.

Rufton read: "'In consideration of services rendered, I promise William Jakes three thousand pounds when I settle with Sir Charles Trevor. Signed, John Hawke.'"

"A palpable forgery! I guessed as much, cried Sir John.

"Who knows Sir John's signature?"

"I do," said Sir Charles Sunbury,

"Is that it?"

"Well, I should say so."

"Tut, the fellow is a born forger!" cried Hawker.

The Duke looked at the back of the paper, and read: "'To Thomas Cribb, Licensed Dealer in Beer, Wine, Spirits and Tobacco.' It is certainly paper from the room alluded to."

"He could help himself to that."

"Exactly. The evidence is by no means convincing. At the same time, Sir John, I am compelled to tell you that the way in which you anticipated the evidence has produced a very unpleasant impression in my mind."

"I knew what the fellow was capable of."

"Do you admit being intimate with him?"

"Certainly not."

"You had nothing to do with him?"

"I had occasion recently to horsewhip him for insolence. Hence this charge against me."

"You knew him very slightly?"

"Hardly at all."

"You did not correspond!"

"Certainly not."

"Strange, then, that he should have been able to copy your signature if he had no letter of yours."

"I know nothing of that."

"You quarreled with him recently?"

"Yes, sir. He was impertinent and I beat him."

"Had you any reason to think you would quarrel?"

"No, sir."

"Does it not seem strange to you then that he should have been keeping the cards all these weeks to buttress up a false charge againt you, if he had no idea that an occasion for such a charge would ever arise?"

"I cannot answer for his actions," said Hawker in a sullen voice.

"Of course not. At the same time I am forced to repeat, Sir John, that your anticipatilon of this document has seemed to me exactly what might be expected from a man of strong character who knew that such a document existed."

"I am not responsible for this man's assertions, nor can I control Your Grace's speculations, save to say that so far as they threaten my honour, they are contemptible and absurd. I place my case in the bands of the committee. You know, or can easily learn, the character of this man Jakes. Is it possible that you can hesitate between the words of such a man and the character of one who has for years been a fellow member of this club?"

"I am bound to say, Your Grace," said Sir Charles Dunbury, "that, while I associate myself with every remark which has fallen from you, I am still of the opinion that the evidence is of so corrupt a character that it would be impossible for us to take action upon it."

"That is also my opinion," came from several of the committee, and there was a general murmur of acquiescence.

"I thank you, gentlemen," said Hawker, rising. "With your permission, I shall bring this sitting to an end."

"Excuse me, sir; there are two more witnesses," said Lord Rufton.

"Jakes, you can withdraw. Leave the documents with me."

"Thank you, my lord. Good-day, my noble sportsmen. Should any of you want a cock or a terrier—"

"That will do. Leave the room." With many bows and backward glances, William Jakes vanished from the scene.

"I should like to ask Tom Cribb one or two questions," said Lord Rufton. "Call Tom Cribb."

A moment later the burly figure of the champion came heavily into the room. He was dressed exactly like the pictures of John Bull, with blue coat with shining brass buttons, drab trousers and top-boots, while his face, in its broad, bovine serenity, was also the very image of the national prototype. On his head he wore a low-crowned, curly-brimmed hat, which he now whipped off and stuffed under his arm. The worthy Tom was much more alarmed than ever he had been in the ring, and looked helplessly about him like a bull who finds himself in a strange enclosure.

"My respects, gentlemen all!" he repeated several times, touching his forelock.

"Good morning, Tom," said the Duke affably. "Take that chair. How are you?"

"Damned hot, Your Grace. That is to say, very warm. You see, sir, I do my own marketing these days, and when you've been down to Covent Garden and then on to Smithfield, and then trudge back here, and you two stone above your fighting weight—"

"We quite understand. The chief steward will see to you presently."

"I want to ask you, Tom," said Lord Rufton, "do you remember the evening of May third last in your parlour?"

"I heard there was some barney about it, and I've been lookin' it up," said Tom. "Yes, I remember it well, for it was the night when a novice had the better of old Ben Burn. Lor', I couldn't but laugh. Old Ben got one on the mark in the first round, and before he could get his wind—"

"Never mind, Tom. We'll have that later. Do you recognise these cards?"

"Why, those cards are out of my parlour. I get them a dozen at a time, a shilling each, from Ned Summers of Oxford Street; the same what—"

"Well, that's settled then. Now, do you remember seeing Sir John here and Sir Charles Trevor that evening!"

"Yes, I do. I remember saying to Sir John that he must play light with my novices, for there was one cove, Bill Summers my name, out of Norwich, and when Sir John—"

"Never mind that, Tom, Tell us, now, did you see Sir John and the bookmaker, Jakes, together that night? "

"Jakes was there, for he says to the girl in the bar, 'How much money have you, my lass?' And I said, 'You dirty dog—'"

"Enough, Tom. Did you see the man Jakes and Sir John together?"

"Yes, sir; when I came into the parlour after the bout between Shelton and Scroggins. I saw the two of them alone, and Jakes, he said that they had done business together. "

"Did they seem friendly?"

"Well, now you ask it, Sir John didn't seem too pleased. But, Lord love you, I'm that busy those evenings that if you dropped a shot on my head I'd hardly notice it."

"Nothing more to tell us?"

"I don't know as I have. I'd be glad to get back to my bar."

"Very good, Tom. You can go."

"I'd just remind you gentlemen that it's my benefit at the Five Court, St. Martin's Lane, come Tuesday week." Tom bobbed hill bullet-head many times and departed.

"Not much in all that," remarked the Duke. "Does that finish the case?"

"There is one more, Your Grace. Call the girl Lucy. She is the girl of the private bar."

"Yes, yes, I remember," cried the Duke. "That is to say, by any means. What does this young person know about it?"

"I believe that she was present." As Lord Rufton spoke, Lucy, very nervous, but cheered by the knowledge that she was in her best Sunday clothes, appeared at the door.

"Don't be nervous, my girl. Take this chair," laid Lord Rufton kindly. "Don't keep on curtsying. St down."

The girl sat timidly on the edge of the chair. Suddenly her eyes caught those of the august chairman.

"Why, Lord bless me!" she said. "It's the little Duke!"

"Hush, my girl, hush"" His Grace held up a warning hand.

"Well, I never!" cried Lucy, and began to giggle and hide her blushing face In her handkerchief.

"Now, now!" said the Duke. "This is a grave business! What are you laughing at?"

"I couldn't help it, sir. I was thinking of that evening down in the private bar when you bet you could walk a chalk line with a bottle of champagne on your head."

There was a general laugh, in which the Duke joined.

"I fear, gentlemen , I must have had a couple in my head before I ventured such a feat. Now, my good girl, we did not ask you here for the sake of your reminiscences. You may have seen some of us unbending: but we will let that pass... You were in the bar on May the third?"

"I'm always there."

"Cast your mind back and recall the evening when Sir Charles Trevor and Sir John Hawker proposed to cut cards for money."

"I remember it well, sir."

"After the others had left the bar, Sir John and a man named Jakes are said to have remained behind."

"I saw them."

"It's a lie! It's a plot!" cried Hawker.

"Now, Sir John, I must really beg you!" It was the Duke who was cross- questioning now. "Describe to us what you saw."

"Well, sir, they began talking over a pack of cards. Sir John up with his hand, and I was about to call for West Country Dick — he's the chucker-out you know, sir, at the Union Arms — but no blow passed and they talked very earnest-like for a time. Then Mr. Jakes called for paper and wrote something, and that's all I know except that Sir John seemed very upset."

"Did you ever see that piece of paper before?" The Duke held it up.

"Why, sir, it looks like Mr. Cribb's bill-head."

"Exactly. Was it a piece like that which you gave to these gentlemen that night!"

"Yes, sir."

"Could you distinguish it?"

"Why, sir, now that I come to think of it, I could."

Hawker sprang up with a convulsed face. "I've had enough of this nonsense. I'm going."

"No, no; Sir John. Sit down again. Your honour demands Your presence... Well, my good girl, you say you could recognise it?"

"Yes, sir, I could. There was a mark, sir. I drew some burgundy for Sir Charles, sir, and some slopped on the counter. The paper Wall marked with It on the aide. I was in doubt if I should give them so soiled a piece."

The Duke looked very grave. "Gentlemen, this is a serious matter. There is, as you see, a red stain upon the side of the paper. Have you any remark to make, Sir John?"

"A conspiracy, Your Grace! An infernal, devilish plot against a gentleman's honour."

"You may go, Lucy." said Lord Rufton, and with curtsies and giggles, the barmaid disappeared.

"You have heard the evidence, gentlemen," said the Duke. "Some of you may know the character of this girl, which is by all accounts excellent."

"A drab out of the gutter!"

"I think not, Sir John; nor do you improve your position by such assertions. You will each have your own impression as to how far the girl's account seemed honest and carried conviction with it. You will observe that had she merely intended to injure Sir John, her obvious method would have been to have said she overheard the conversation detailed by the witness, Jakes. This she has not done. Her account, however, tends to corroborate—"

"Your Grace," cried Hawker, "I have had enough of this!"

"We shall not detain you much longer, Sir John Hawker," said the chairman, "but for that limited time we must insist upon your presence."

"Insist, sir!"

"Yes, sir, insist."

"This is strange talk."

"Be seated, sir. This matter must go to a finish."

"Well!" Hawker fell back into his chair.

"Gentlemen," said the Duke, "Slips of paper are before you. After the custom of the club, you will kindly record your opinion and hand to me. Mr. Poyntz? I thank you. Vandeleur! Bunbury! Hurton! General Scott! Colonel Turton! I thank you."

He examinded the papers. "Exactly. You are unanimous! I may say that I entirely agree with your opinion." The Duke's rosy kindly face had set as hard as flint.

"What am I to understand by this, sir" cried Hawker.

"Bring the club book," said the Duke. Lord Rufton carried across a large brown volume from the side-table and opened it before the chairman.

"C, D, E, F, G — Ah, here we are — H. Let us see! Houston, Harcourt, Hume, Duke of Hamilton I have it — Hawker. Sir John Hawker, your name is forever erased from the book of Watier's Club."

He drew the pen across the page as he spoke. Hawker sprang frantically to his feet.

"You cannot mean it! Consider, sir; this is social ruin! Where shall I show my face if I am cast from my club? I could not walk the streets of London. Take it back, sir! Reconsider it!"

"Sir John Hawker, "we can only refer you to Rule 19. It says: 'If any member shall be guilty of conduct unworthy of an honourable man, and the said offense be established to the unanimous satisfaction of the committee, then the aforesaid member shall be expelled the club without appeal.'"

"Gentlemen," cried Hawker, "I beg you not to be precipitate! You have had the evidence of a rascal bookmaker and of a serving wench. Is that enough to ruin a gentleman's life? I am undone if this goes through."

"The matter has been considered and is now in order. We can only refer you to Rule 19."

"Your Grace, you cannot know what this will mean. How can I live? Where can I go? I never asked mercy of man before. But I ask it now. I implore it, gentlemen. Reconsider your decision!"

"Rule 19."

"It is ruin, I tell you — disgrace and ruin!"

"Rule 19."

"Let me resign. Do not expel me."

"Rule 19."

It was hopeless, and Hawker knew it. He strode in front of the table.

"Curse your rules! Curse you, too, you silly, babbling jackanapes. Curse you all — you, Vandeleur, and you, Poyntz, and you, Scott, you doddering toast-and-water gamester. You will live to mourn the day you put this indignity upon me. You will answer it — every man of you! I'll set my mark on you. By the Lord I will! You first, Rufton. One by one, I'll weed you out! I've a bullet for each. I'll number 'em!"

"Sir John Hawker," said the Duke, "this club is for the use of members only. May I ask you to take yourself out of it?"

"And if I don't — what then?"

The Duke turned to General Scott. "Will you ask the hall porters to step up?"

"There! I'll go!" yelled Hawker. "I will not be thrown out — the laughing stock of Jermyn Street. But you will hear more, gentlemen. You will remember me yet. Rascals! Rascals everyone!"

And so it was, raving and stamping, with his clenched hands waving above his head, that Devil Hawker passed out from Watier's Club and from the social life of London.

For it was his end. In vain he sent furious challenges to the members of the committee. He was outside the pale, and no one would condescend to meet him. In vain he thrashed Sir Charles Bunbury in front of Limmer's Hotel. Hired ruffians were put upon his track and he was terribly thrashed in return. Even the bookmakers would have no more to do with him, and he was warned off the turf. Down he sank, and down, drinking to uphold his spirits until he was but a bloated wreck of the man that he had been.

And so, at last, one morning in his rooms in Charles Street, that dueling pistol which had so often been the instrument of his vengeance was turned upon himself, and that dark face, terrible even in death, was found outlined against a blood-sodden pillow in the morning.

So put the print back among the pile. You may be the better for having honest Tom Cribb upon your wall, or even the effeminate Brummell. But Devil Hawker never, in life or death, brought luck to anyone. Leave him there where you found him, In the dusty old shop of Drury Lane.