Dr. Conan Doyle and His Stories

Dr. Conan Doyle and His Stories is two articles written by Archibald Cromwell and Hugh S. M. A. Clauchlan, first published in The Windsor Magazine in october 1896. They were used as an introduction of The Three Correspondents published in the same issue.

Editions

- in The Windsor Magazine (october 1896 [UK]) 1 photo, 1 ill. by H. C. Seppings-Wright, 1 ill. by Arthur Cooke

Illustrations

- Illustrations in The Windsor Magazine (october 1896)

-

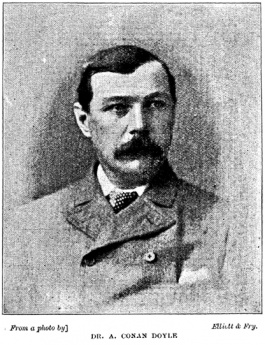

DR. A. CONAN DOYLE, From a photo by Elliott & Fry

-

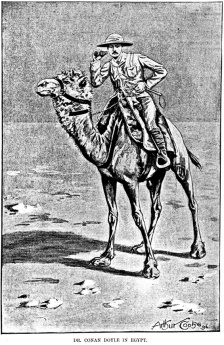

DR. CONAN DOYLE PARTS COMPANY WITH HIS CAMEL.

(Reproduced from the "Illustrated London News" by kind permission.) -

DR. CONAN DOYLE IN EGYPT.

Dr. Conan Doyle and His Stories

(october 1896, p. 367)

(october 1896, p. 368)

(october 1896, p. 369)

(october 1896, p. 370)

(october 1896, p. 371)

(october 1896, p. 372)

Special attention is directed to the story by Dr. Conan Doyle, entitled "THE THREE CORRESPONDENTS," which, appearing in this issue, gives additional interest to the following article.

I. A PEN PORTRAIT OF THE AUTHOR.

by ARCHIBALD CROMWELL.

Illustrated by H. C. SEPPINGS-WRIGHT.

The creator of "Sherlock Holmes" was born in Edinburgh thirty-seven years ago. His grandfather was John Doyle, whose celebrated caricatures were signed HP, a signature chosen because it contains the artist's initials, I. D., superscribed. Conan Doyle was educated at Stonyhurst, in Lancashire, and subsequently in Germany. In 1876 he began the study of medicine in the University of Edinburgh. He came to Southsea, and had a considerable practice. When the supposed cure for consumption was being exploited on the Continent, Dr. Doyle made a careful and exhaustive inquiry into it, writing an exceedingly able treatise as a result. Ever since he was a schoolboy his pen had been busy, and at the age of nineteen his story "The Mystery of the Sassassa Valley" was printed in Chambers's Journal. As a relief to his more serious work, Dr. Doyle wrote various short stories at Southsea, some of which have been republished under the title of "The Captain of the Polestar." The thrilling story "A Study in Scarlet" is specially familiar to our readers as it was presented with the Christmas number of the WINDSOR MAGAZINE in 1895. Next the volume " Micah Clarke " attracted extraordinary attention, and lifted its author into the front rank at once. Following this "The Sign of Four" was published, and then "The White Company."

The success which came so swiftly caused Dr. Doyle to devote himself solely to literature, a decision at which he arrived only after serious consideration. His medical experience has been of the utmost value to him, and perhaps his skill as an oculist served to intensify that extraordinary perception which is the characteristic of Sherlock Holines. At all events there has been a good deal of doctor's life portrayed by Dr. Doyle in his books. "The Stark-Munro Letters," which first appeared serially in the Idler, strike one as an excuse for airing many whimsical ideas which had occurred to the author in his own career. Another volume, "Round the Red Lamp," deals with a doctor's experiences.

Of "The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes," and "The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes," one needs to say little, for the fame which the great detective has attained is world wide. Dr. Doyle published in 1893 "The Refugees," a story which easily succeeds in thrilling all readers.

Sir Henry Irving produced Dr. Doyle's one-act play, "A Story of Waterloo," first at Bristol, where it was received with extreme favour, and subsequently in London. Dr. Doyle's realisation of the octogenarian Corporal Gregory Brewster is a masterpiece which might well satisfy the British public, especially when Irving sustained the rôle of the garrulous corporal. It is very possible that Dr. Doyle will enhance his reputation as a dramatist by some other plays, for his work lends itself well to stage representation.

After being successively a doctor, a novelist, and a playwright, Dr. Doyle must needs yearn for yet another experience, that of a special correspondent. Accordingly he went out to Egypt to act as a "Scene-painter of history" for the Westminster Gazette. The story which is printed in this issue is one result of his adventures in the desert. The illustrations of Dr. Doyle on and off a camel are also reminiscent of his Egyptian campaign. His letters from the land of the sphinx were pleasantly informative, and suggest that were he to follow in the foot-steps of William Howard Russell and Archibald Forbes the world would gain a brilliant "special." After the burning heat of the desert, which bronzed Dr. Doyle till his countenance resembled the hue of a fashionable brown shoe, came a chance of enjoying the cool breezes of the heights of Hindhead, where a fine house is rapidly rising as a residence for Dr. Doyle. It is to be hoped that this Alpine air, which did so much good to the late Professor Tyndall and has enabled Mr. Grant Allen to endure an English winter, may prove beneficial to the health of Mrs. Conan Doyle. And if this be the case the Engadine will lose what Haslemere gains, the presence of Dr. Doyle and his charming wife.

II. AN APPRECIATION OF DR. DOYLE'S WORK.

By HUGH S. M. A. CLAUCHLAN.

Illustrated by ARTHUR COOKE.

The permanent place of Dr. A. Conan Doyle in British fiction is as yet an undetermined quantity. The best of his years, that are still to come, must settle the point. A critical foot-rule may be applied to declining forces in letters with something like finality, but not to forces that are in process of expansion. That is the happy state of the author of " The White Company." He is an expanding force in the region of romances.

The way was not clear to him from the first. Destiny played its usual tricks, leading him on through medical class-rooms and hospitals, then by the way of a doctor's work afloat in a whaler and on a steamship on the West African Coast, to private practice as a physician in Southsea.

It seems but yesterday that his big manly form was as familiar in Southsea streets as that of any naval officer from the dockyard. He was a story-teller then, and for years before it. A story of his had been published in Chambers's Journal when he was a youth of nineteen, and six years later he had scaled the pages of the Cornhill with his weird Habakkuk Jephson's Statement, a tale that formed the foundation of his steadfast friendship with Mr. James Payn. All the same; he was an amateur then, and for some years after, and he would merrily dismiss the notion that he could ever abandon his profession for the chances of literature.

Perhaps he was not so convinced of it as he seemed. The manuscript of "Micah Clarke" was growing in the small hours, and Decimus Saxon and Sir Gervas Jerome were waiting to take their places beside Dugald Dalgety among immortal soldiers of fortune, as void of conscience as of fear.

The reception of Micah commenced the work of undermining his author's resolve to stick to his profession. The sudden, unprecedented delight of readers in the creation of Sherlock Holmes completed it. Continued practice as a physician was impossible for a writer so convincing and so versatile. He threw physic to the dogs — the prescription of it at least ; he kept the training. The risk, if there was any risk, soon vanished. Publishers, who in the early days dallied with his manuscripts, now pleaded for them. The few years that have passed since then have seen great achievements, and one of the greatest of them is in process of disclosure. There should be others before the sum is made of his place in letters, and his influence on character and taste. He had to pick his steps across a profession to his real life-work, but the adventure and research of his early years were an equipment of experience which, with his keen eye, memory, and marvellous gift of fusing facts, helped him to firm footing with almost dangerous rapidity.

Well under middle age, and a man of magnificent constitution and wholesome habits, he should have the best of his life and work before him. What Dr. Conan Doyle has done may have to be told in after years. The present-day critic must be content to examine what he aims at doing.

A big company of readers who were captivated by the first of the historical romances live in a state of perpetual revolt against one popular estimate of Dr. Conan Doyle as a writer of detective stories. They grudge him an even momentary descent to a lower plane. There may be a little injustice in this view. Conclusions are oddly reached, and out of one's very loyalty to an author's reputation may spring an unfair disparagement of a portion of his work. This curious state of mind is illustrated in those who have taken Sir Nigil Loring to their hearts and wander through the centuries that have been called back for their benefit in "The White Company" and "The Refugees." They don't do justice to Sherlock Holmes. The man whose creative work is best in any department of fiction has done a great thing, and this is, the case with Dr. Conan Doyle and his detective. Even in his retirement from that class of story Dr. Doyle remains supreme. Surely it is no slight matter to have given birth to a character of such world-wide celebrity as the quick-witted master of the art of deduction, who seems to have permanently enriched the vocabulary of simile in half a dozen languages. This is a scientific age, and it may be that Sherlock Holmes will take his place beside Sam Weller as a standard illustration, to be drawn upon unrestrained by writers of leading articles and comic opera librettists, and within narrower limits by preachers and after-dinner speakers.

Dr. Doyle was at the Pyramids a few months ago, and a strange story has been whispered in this country of an announcement that was made to him by his hotel keeper. He was informed — so the story goes — that Sherlock Holmes had been translated into Arabic and issued to the local police as a text-book. The Nile valley has its humorists, unconscious or otherwise. The ingenious construction of these detective stories, their surprises, so logical even in their wildest forms, the never-failing scientific touch, the countless evidences that they are tapping an almost unique store of curious knowledge, the survey of motive they disclose, at once wide and minute — all these things contribute to place the Sherlock Holmes series on a distinct level of art without sacrificing one atom of the brisk movement and appetising sensation that gripped the million. This may consistently be urged without holding that Dr. Doyle was guilty of culpable homicide in tumbling his detective over the cliff, and steadfastly rejecting every inducement to reanimate him.

Much of Dr. Doyle's success in the detective story may be traced to his medical training. Constructive skill is his by nature, and a rare gift of narrative, but the scientific aspect is the most fascinating aspect of crime, and the hardest to be disclosed by investigators. It is here that the years in the medical school of Edinburgh have told their tale. This scientific touch must in some degree colour all his work. The grim and powerful pictures of what falls into a doctor's life, told "Round the Red Lamp," are the direct outcome of it, and it shows itself in some of his earlier minor efforts, among them "The Physiologist's Wife," one of the most perfect of his short stories.

The much-debated "Stark Munro Letters," which probably contain more of the actual man who wrote them than anything he has done, are as much the outpourings of a scientific observer as of an eager prober into the faiths that inspire human action and the forms that limit it. The transitory stage in the author's progress is the one in which the profession was paramount. There was a wider field for him to cover, a greater range of centuries and peoples, and conditions of life and battle. "Micah Clarke" had given brilliant proof of his capacity to paint history in strong and true colours on large canvases. The conviction that historical romance was his destiny was superbly confirmed by "The White Company," and with "The Refugees" and "The Great Shadow" became an acknowledged fact. Garrulous Brigadier Gerard has helped to strengthen the base of this grateful expectation, and although "Rodney Stone" is only midway in his career at the time of writing, the romance, with its dashing, boisterous movement and masterful grasp, vies in fascination with any one of its predecessors. The champing of steeds, the clang of armour, the hum of arrows, the clash of cutlasses, the roll of drums, the rattle of musketry alternately assail the ears of readers in these moving tales. There is little time in them for repose or reflection once the author's narrative is fairly under way. His is the direct method. Broad effects splash his books as if he had seized his ill-armed sectaries in the Monmouth rising, or his incomparably drawn archers in the Spanish war, and spurred them headlong through his pages. They must be poor pulses that do not beat more quickly under the excitement of these breathless, life and death passages. Parry and thrust, rough jests to lighten peril, the broken bivouac, cut-throat courtesies that would force smiles in a torture-chamber, polished rapiers, wits and manners — these things dazzle us like a winter sun on ice. So strong are the effects that a reader may fail to detect how much they owe to the careful treatment of detail.

Dr. Conan Doyle is not one of those writers who grudge labour on their work ; lie leaves nothing to chance. A hundred and fifty volumes dealing with the period he had chosen was the sum of his reading before he wrote a line of "The White Company." No imagination, no creative power, however brilliant, if unaided by patient research, could have pictured the English archer as Dr. Doyle has given him to literature. The delineation of the abbey life at Beaulieu is not only picturesque but accurate. Instances might be multiplied of the author's high sense of duty as a teacher as well as an entertainer. A score of vivid, truthful touches declare it in the drawing of that early English day in the New Forest when the young priest of "The White Company" broke through monastic restraints at the call of a fuller life. The fresh presentment of the French Court in the early chapters of "The Refugees" tells the same story, and so do the Georgian echoes in "Rodney Stone" of Corinthian England during the wars' with France. Nothing slipshod mars the movement or the scene. These are romances of action with the distinction of honesty and thoroughness in every line.

A similar thoroughness marks the characterisation. Passing personages who appear and go in a chapter are shaped with infinite care, as if their presence in the tale were more than migratory. No better example of this could be found than the Canadian priest in "The Refugees," who lives his life of brave suffering in two pages and goes out of sight, but never out of memory. Throughout the Doyle romances there is evidenced a passionate fondness for the sturdy qualities that make the successful man of action. Manliness and big-hearted vision are the distinctions of the author himself ; he looks behind creeds and over the heads of parties to the back of things. Affectations and insincerities are as foreign to him as they were to Reuben Clarke of Havant or to his son Micah, who was eminently a man of his own making. He is not impatient with weakness, like men of less sympathetic sight, but he revels in honest, outspoken strength. This catholicity of admiration leads him to form a juster estimate of the conventicle spirit than Sir Walter Scott could do, although by nature inclining to the king's men.

Above all things, he is at heart a soldier, with a preference for a good cause, but in any case he must have the shock of arms. His soldiers of fortune are among the choicest possessions of modern fiction. Who is there who would not revel in the delicate savagery of Sir Nigil Loring, that most docile of husbands and keenest of jousters, whose invitations to slaughter were clothed in such quaint courtesies ? Never was bloodthirstiness so affable as his. What grotesque is there in battle books to surpass Decimus Saxon ? From the moment of his appearance on the scene, fished out of the Solent with his letters to the faithful, this lean, hardy, fighting man, who has not a scrap of character to his scraggy back, but who can give points in generalship to all the king's officers, not to speak of Monmouth's rabble, keeps eyes focused on him as if lie would not have slit a throat for a new pair of jackboots.

Dr. Doyle peoples his pages with these delicious creations, so humorously developed and so original in design. It does not follow that the man who can picture soldiers can draw battles, but the gifts are concurrent in the author of "The White Company." Perhaps his finest battle-piece is the description of Waterloo in "The Great Shadow," but Sedgemoor also is presented with splendid power in "Micah Clarke," and there is never a bit of fighting on sca or land that does not call out his clearest and most forcible quality of descriptive writing. The emotions he most effectively deals with are those that are expressed in violent dramatic action. What a war correspondent he may make, sonic day when there is real war ! Just at this time it is useful to reflect on one debt of gratitude the reader of fiction owes to Dr. Conan Doyle — that for his wholesomeness. Everything about him is. healthy and good-tempered. There are no distortions in his mind to make us shudder, not an atom of cynicism or disbelief in ultimate good. His bloodshed is the result, of honest, downright fighting, with no unhealthy horrors to make the sacrifice of life in adventure hideous. His men die so gamely that even their corpses seem companionable. Courage and honour are allied in Sir Nigel Loring, and his best enthusiasms are always for the right. This inclination to enthusiasm has kept Dr. Doyle a boy in heart. Whatever he has done in life has been done enthusiastically No cricketer ever centred his energies more completely than he on the winning of a match. In practice, he decided to become an eye specialist, and even when his reputation in letters was growing fast he would not listen to suggestions that would divorce him from an oculist's work. There was no object so wonderful, so fascinating as the human eye. He was drawn by it to Vienna as a student, and to London as a practitioner, holding at arm's length, while he could, the temptations to lure him into fiction as a settled thing. And now it is only the object, that has changed ; the enthusiasm is still there, the joy in action and honest motive that tells of a sound soul.

No suspicion of decadence taints his estimate of the world. Crime and vice, when he treats of them, are hunian nature's excrescences, not its component parts. There is no dwarfing of manliness to make the juice of his romances bitter to the taste. His influence is above all things a healthy one, a stimulant to action, an antidote to lethargy and despair. Nor is there any leaven of careless thinking to reduce the value of this fine influence. Dr. Conan Doyle is a student and a scholar as well as a creative writer, with a high sense of responsibility to guard him against any pitfall of unconscientious work. He is master of the periods he recreates, and fills in his inimitable backgrounds with the touch of intimate knowledge. An intense national pride in the past he pictures, and a firm belief that his country is worthy of its traditions, inspires and colours all he does. Novelist, teacher, and patriotic Briton, Dr. Conan Doyle is a name of whom English letters may well be proud.