Shakespeare's Expostulation

Shakespeare's Expostulation is a poem written by Arthur Conan Doyle first published in The Cornhill Magazine in march 1909, and collected in Songs of the Road on 16 march 1911.

Arthur Conan Doyle's contribution to the Shakespeare authorship debate. The poem speaks in the plaintive voice of Shakespeare himself, complaining at the attribution of authorship of his works to Francis Bacon.

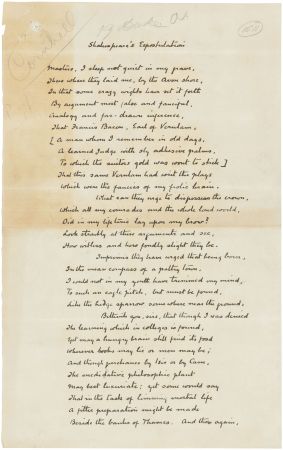

Manuscript

The manuscript has 3 pages.

-

p. 1

Auctions

- Christie's London, 10 july 2019, lot 580. GBP 2,125.

Editions

- in The Cornhill Magazine (march 1909 [UK])

- in Songs of the Road (16 march 1911, Smith, Elder & Co. [UK])

- in Songs of the Road (october 1911, Doubleday, Page & Co. [US])

- in Songs of the Road (27 january 1920, John Murray [UK])

- in Songs of the Road (february 1920, John Murray [UK])

- in The Poems of Arthur Conan Doyle (21 september 1922, John Murray [UK])

- in The Poems of Arthur Conan Doyle (14 september 1928, John Murray's Fiction Library [UK])

Shakespeare's Expostulation

Masters, I sleep not quiet in my grave,

There where they laid me, by the Avon shore,

In that some crazy wights have set it forth

By arguments most false and fanciful,

Analogy and far-drawn inference,

That Francis Bacon, Earl of Verulam

(A man whom I remember in old days,

A learned judge with sly adhesive palms,

To which the suitor's gold was wont to stick) —

That this same Verulam had writ the plays

Which were the fancies of my frolic brain.

What can they urge to dispossess the crown

Which all my comrades and the whole loud world

Did in my lifetime lay upon my brow?

Look straitly at these arguments and see

How witless and how fondly slight they be.

Imprimis, they have urged that, being born

In the mean compass of a paltry town,

I could not in my youth have trimmed my mind

To such an eagle pitch, but must be found,

Like the hedge sparrow, somewhere near the ground.

Bethink you, sirs, that though I was denied

The learning which in colleges is found,

Yet may a hungry brain still find its food

Wherever books may lie or men may be;

And though perchance by Isis or by Cam

The meditative, philosophic plant

May best luxuriate; yet some would say

That in the task of limning mortal life

A fitter preparation might be made

Beside the banks of Thames. And then again,

If I be suspect, in that I was not

A fellow of a college, how, I pray,

Will Jonson pass, or Marlowe, or the rest,

Whose measured verse treads with as proud a gait

As that which was my own? Whence did they suck

This honey that they stored? Can you recite

The vantages which each of these has had

And I had not? Or is the argument

That my Lord Verulam hath written all,

And covers in his wide-embracing self

The stolen fame of twenty smaller men?

You prate about my learning. I would urge

My want of learning rather as a proof

That I am still myself. Have I not traced

A seaboard to Bohemia, and made

The cannons roar a whole wide century

Before the first was forged? Think you, then,

That he, the ever-learned Verulam,

Would have erred thus? So may my very faults

In their gross falseness prove that I am true,

And by that falseness gender truth in you.

And what is left? They say that they have found

A script, wherein the writer tells my Lord

He is a secret poet. True enough!

But surely now that secret is o'er past.

Have you not read his poems? Know you not

That in our day a learned chancellor

Might better far dispense unjustest law

Than be suspect of such frivolity

As lies in verse? Therefore his poetry

Was secret. Now that he is gone

'Tis so no longer. You may read his verse,

And judge if mine be better or be worse:

Read and pronounce! The meed of praise is thine;

But still let his be his and mine be mine.

I say no more; but how can you for-swear

Outspoken Jonson, he who knew me well;

So, too, the epitaph which still you read?

Think you they faced my sepulchre with lies —

Gross lies, so evident and palpable

That every townsman must have wot of it,

And not a worshipper within the church

But must have smiled to see the marbled fraud?

Surely this touches you? But if by chance

My reasoning still leaves you obdurate,

I'll lay one final plea. I pray you look

On my presentment, as it reaches you.

My features shall be sponsors for my fame;

My brow shall speak when Shakespeare's voice is dumb,

And be his warrant in an age to come.