The British Campaign in France (april 1916)

| The British Campaign in France 2/21 >> |

(The Strand Magazine, april 1916, p. 339)

The British Campaign in France. I. The Battle of Mons is the first article, published in april 1916, in a series of 21 articles written by Arthur Conan Doyle serialized in The Strand Magazine.

Editions

- in The Strand Magazine (april 1916 [UK]) (2 maps, 3 photos, 4 ill. by Richard Caton Woodville and others)

- in Everybody's Magazine (june 1916 [UK])

- in The British Campaign in France and Flanders (1916-1920, Hodder & Stoughton Ltd. [UK])

- in The British Campaign in France and Flanders (1916, George H. Doran Co. [US])

- in The British Campaign in Europe (1914-1918) (november 1928, Geoffrey Bles [UK])

Illustrations

The British Campaign in France (april 1916)

(The Strand Magazine, april 1916, p. 338)

(The Strand Magazine, april 1916, p. 339)

(The Strand Magazine, april 1916, p. 340)

(The Strand Magazine, april 1916, p. 341)

(The Strand Magazine, april 1916, p. 342)

(The Strand Magazine, april 1916, p. 343)

(The Strand Magazine, april 1916, p. 344)

(The Strand Magazine, april 1916, p. 345)

(The Strand Magazine, april 1916, p. 346)

(The Strand Magazine, april 1916, p. 347)

(The Strand Magazine, april 1916, p. 348)

(The Strand Magazine, april 1916, p. 349)

(The Strand Magazine, april 1916, p. 350)

(The Strand Magazine, april 1916, p. 351)

(The Strand Magazine, april 1916, p. 352)

(The Strand Magazine, april 1916, p. 353)

Foreword

The time has now come when, owing to the long period which has elapsed, and the changes which have been made in the Army units, the particulars of the doings of the regiments of the British Army in France and in Flanders can be given with some approach to accurate detail. From the first days of the war the author has devoted his time to the accumulation of evidence from first-hand sources as to the various happenings of these great days. He has built up his narrative from letters, diaries, and interviews, from the hand or lips of men who have been leaders in our glorious armies, whose deeds it was his ambition to understand and to chronicle. In many cases he has been privileged to submit his descriptions of the principal incidents to prominent actors in them and to receive their corrections or endorsement. It is not to be supposed that all is here set down, for it will be many years before so great a story is unfolded, but the chronicler would wish to impress one fact upon the public, which is that he has nowhere found need of suppression, that there are no facts to conceal, and that the record of heroic endeavours has never, so far as his researches go, sunk below the very highest which the nation could demand. In this record our temporary set - backs have been treated as frankly as our successes, and there has been no attempt to flinch from the truth.

How great the scope is for such a history may readily be judged by the reader who asks himself what does the public really know of the Battle of Mons, the first occasion in history in which the German and the Briton stood face to face as enemies? What does it know of the tragic but glorious Battle of Le Cateau, where three divisions of the British Army stood during the greater part of a long August day against seven divisions of Germans, and withdrew unbroken? What does it know of the details of the famous retreat, one of the most remarkable withdrawals, in the face of a valiant and energetic enemy, that has ever been known in military history? What does it know of the first Battle of Ypres, when the immortal Regular Army was so worn that some famous regiments were no greater than platoons, though they still barred the German passage to the coast? The true record of these and of every subsequent event will be found in the succeeding pages, so far as it is now possible to collect and arrange them.

The first chapters, dealing with the events which led up to the war, are here omitted, and the narrative begins with the actual campaign.

Chapter I. The Battle of Mons

The Landing of the British in France — The British Leaders — The Advance to Mons — The Defence of the Bridges of Nimy — The Holding of the Canal — The Fateful Telegram.

The Landing of the British in France

The bulk of the British Expeditionary Force passed over to France under the cover of darkness on the nights of August 12th and 13th. The movement, which included the greater part of three army corps and a cavalry division, necessitated the transportation of approximately one hundred thousand men, fifteen thousand horses, and four hundred guns. It is doubtful if so large a host has ever been moved by water in so short a time in all the annals of military history. There was drama in the secrecy and celerity of the affair. Two canvas walls converging into a funnel screened the approaches to Southampton Dock. All beyond was darkness and mystery. Down this fatal funnel passed the flower of the youth of Britain, and their folk saw them no more. They had embarked upon the great adventure of the German War. The crowds in the streets saw the last serried files vanish into the darkness of the docks, heard the measured tramp upon the stone quays dying farther away in the silence of the night, until at last all was still and the great steamers were pushing out into the darkness.

No finer force for technical efficiency, and no body of men more hot-hearted in their keen desire to serve their country, have ever left the shores of Britain. It is a conservative estimate to say that within four months a half of their number were either dead or in the hospitals. They were destined for great glory, and for that great loss which is the measure of their glory.

Belated pedestrians upon the beach of the southern towns have recorded their impression of that amazing spectacle. In the clear summer night the wall of transports seemed to stretch from horizon to horizon. Guardian warships flanked the mighty column, while swift lights shooting across the surface of the sea showed where the torpedo boats and submarines were nosing and ferreting for any possible enemy. But far away, hundreds of miles to the north, lay the real protection of the flotilla, where the smooth waters of the Heligoland Bight were broken by the sudden rise and dip of the blockading periscopes.

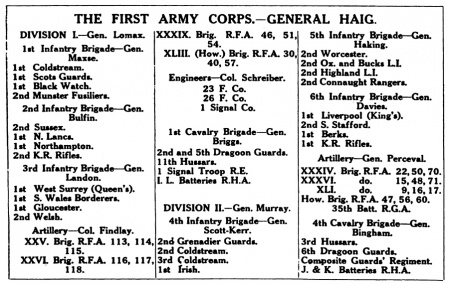

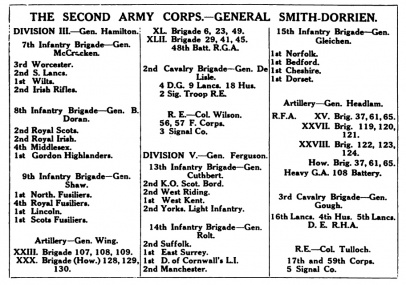

It is well to state, once for all, the composition of this force, so that in the succeeding pages, when a brigade or division is under discussion, the diligent reader may ascertain its composition. This, then, is the First Army which set forth to France. Others will be chronicled as they appeared upon the scene, of action, so far as discretion will allow. It may be remarked that the formation of units has been now greatly altered from the earlier days of the campaign.

Such was the Army which set forth to measure itself against the soldiers of Germany. Prussian bravery, capacity, and organizing power had a high reputation among us, and yet we awaited the result with every confidence, if the odds of numbers were not overwhelming. It was generally known that during the period of Sir John French's command the training of the troops had greatly progressed, and many of the men, with nearly all the senior officers, had had experience in the arduous campaign of South Africa. They could also claim those advantages which volunteer troops may hope to have over conscripts. At the same time there was no tendency to underrate the earnest patriotism of our opponents, and we were well aware that even the numerous Socialists who filled their ranks were persuaded, incredible as it ma seem, that the Fatherland was really attacked, a n d were whole-hearted in its defence.

The crossing was safely effected. It has always been the traditional privilege of the British public to grumble at their public servants and to speak of "muddling through" to victory, No doubt the criticism has often been deserved. But on this occasion the supervising General in command, the British War Office, and the Naval Transport Department all rose to a supreme degree of excellence in their arrangements. The details were meticulously correct. Without the loss of man, horse, or gun, the soldiers who had seen the sun set in Hampshire saw it rise in Picardy or in Normandy. Boulogne and Havre were the chief ports of disembarkation, but many, including the cavalry, went up the Seine and came ashore at Rouen. The soldiers everywhere received a rapturous welcome from the populace, which they returned by a cheerful sobriety of behaviour. The admirable precepts as to wine and women set forth in Lord Kitchener's parting orders to the Army seem to have been most scrupulously observed. It is no slight upon the gallantry of France — the very home of gallantry — if it be said that she profited greatly at this strained, over-anxious time by the arrival of these boisterous over-sea Allies. The tradition of British solemnity has been for ever killed by these jovial invaders. The dusty, poplar-lined roads resounded with their songs, and the quiet Picardy villages re-echoed their thunderous and superfluous assurances as to the state of their hearts. All France broke into a smile at the sight of them, and it was at a moment when a smile meant much to France.

The British Leaders

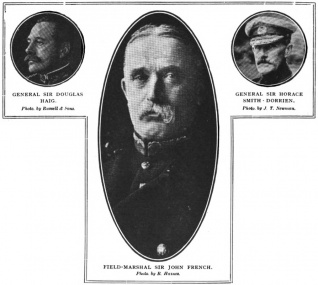

Whilst the various brigades were with some deliberation preparing for an advance up country, there arrived at the Gare du Nord in Paris a single traveller who may be said to have been the most welcome British visitor who ever set foot in the city. He was a short, thick iron, tanned by an outdoor life, a solid. impassive personality with a strong, good-humoured face, the forehead of a thinker above it, and the jaw of an obstinate fighter below. Overhung brows shaded a pair of keen grey eyes, while the strong, set mouth was partly concealed by a grizzled moustache. Such was John French, leader of cavalry in Africa and now Field-Marshal commanding the Expeditionary Forces of Britain. His defence of Colesberg at a critical period when he bluffed the superior Boer forces, his dashing relief of Kimberley, and the gallant way in which he had thrown his exhausted cavalry across the path of Cronje's army in order to hold it while Roberts pinned it down at Paardeburg, were all exploits which were fresh in the public mind, and gave the soldiers confidence in their leader.

French might well appreciate the qualities of his immediate subordinates. Both of his army corps and his cavalry division were in good hands. Haig, like his leader, was a cavalry man by education, though now entrusted with the command of the First Army Corps. Fifty-four years of age, he still preserved all his natural energies, whilst he had behind him long years of varied military experience, including both the Soudanese and the South African campaigns, in both of which he had gained high distinction. He had the advantage of thoroughly understanding the mind of his commander, as he had worked under him as Chief of the Staff in his remarkable operations round Colesberg in those gloomy days which opened the Boer War.

The Second Army Corps sustained a severe loss before ever it reached the field of action, for its commander, General Grierson, died suddenly of heart failure in the train between Havre and Rouen upon August 18th. Grierson had been for many years Military Attaché in Berlin, and one can well imagine how often he had longed to measure British soldiers against the self-sufficient critics around him. At the last moment the ambition of his lifetime was denied him. His place, however, was worthily filled by General Smith-Dorrien, another South African veteran, whose brigade in that difficult campaign had been recognized as one of the very best. Smith-Dorrien was a typical Imperial soldier in the world-wide character of his service, for he had followed the flag, and occasionally preceded it, in Zululand, Egypt, the Soudan, Chitral, and the Tirah before the campaign against the Boers. A sportsman as well as a soldier, he had very particularly won the affections of the Aldershot division by his system of trusting to their honour rather than to compulsion in matters of discipline. It was seldom indeed that his confidence was abused.

Haig and Smith-Dorrien were the two generals upon whom the immediate operations were to devolve, for the Third Army Corps was late, through no fault of its own, in coming into line. There remained the Cavalry Division commanded by General Allenby, who was a column leader in that great class for mounted tactics held in South Africa a dozen years before. It is remarkable that of the four leaders in the initial operations of the German War — French, Smith-Dorrien, Haig, and Allenby — three belonged to the cavalry, an arm which has usually been regarded as active and ornamental rather than intellectual. Pulteney, the commander of the Third Army Corps, was a product of the Guards, a veteran of much service and a well-known heavy-game shot. Thus, neither of the more learned corps were represented among the higher commanders upon the actual field of battle, but brooding over the whole operations was the steadfast, untiring brain of Joffre, whilst across the water the silent Kitchener, remorseless as Destiny, moved the forces of the Empire to the front.

The general plan of campaign was naturally in the hands of General Joffre, since he was in command of far the greater portion of the Allied Force. It has been admitted in France that the original dispositions might be open to criticism, since a number of the French troops had engaged themselves in Alsace and Lorraine to the weakening of the line of battle in the north, where the fate of Paris was to be decided. It is small profit to a nation to injure its rival ever so grievously in the toe when it is itself in imminent danger of being stabbed to the heart. A further change in plan had been caused by the intense sympathy felt both by the French and the British for the gallant Belgians, who had done so much and gained so many valuable days for the Allies. It was felt that it would be unchivalrous not to advance and do what was possible to relieve the intolerable pressure which was crushing them. It was resolved, therefore, to abandon the plan which had been formed, by which. the Germans should be led as far as possible from their base, and to attack them at once. For this purpose the French army changed its whole dispositions, which had been formed on the idea of an attack from the east, and advanced over the Belgian frontier, getting into touch with the enemy at Namur and Charleroi, so as to secure the passages of the Sambre. It was in fulfilling its part as the left of the Allied line that on August 18th and 19th the British troops began to move northwards into Belgium. The First Army Corps advanced through Le Nouvion, St. Remy, and Maubeuge to Rouveroy, which is a village upon the Mons-Chimay road. There it linked on to the Second Corps, which had moved up to the line of the Condé-Mons Canal. On the morning of Sunday, August 23rd, all these troops were in position. The Fifth Brigade of Cavalry (Chetwode's) lay out upon the right front at Binche, but the remainder of the cavalry was brought to a point about five Ales behind the centre of the line, so as to be able to reinforce either flank. The first blood of the land campaign had been drawn upon August 22nd outside Soignies, when a reconnoitring squadron of the 4th Dragoon Guards under Captain Hornby charged and overthrew a body of the 4th German Cuirassiers, bringing back some prisoners. The 10th Hussars had enjoyed a similar experience. It was a small but happy omen.

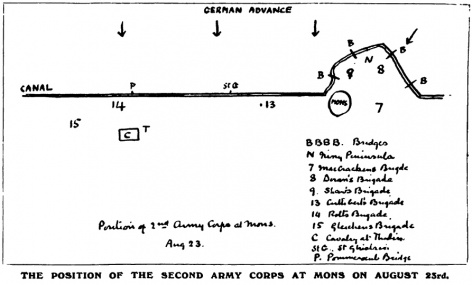

The Advance to Mons

The forces which now awaited the German attack numbered about eighty-six thousand men, who may be roughly divided into seventy-six thousand infantry, ten thousand cavalry, and three hundred and twelve guns. The general alignment was as follows : The First Army Corps held the space between Mons and Binche, which was soon contracted to Bray as the eastward limit. Close to Mons, where the attack was expected to break, since the town is a point of considerable strategic importance, there was a thickening of the line of defence. From that point the Third Division and the Fifth, in the order named, carried on the British formation down the length of the Mons-Condé Canal. The front of the Army covered nearly twenty miles, an excessive strain upon so small a force in the presence of a compact enemy.

If one looks at the general dispositions, it becomes clear that Sir John French was preparing for an attack upon his right flank. From all his information the enemy was to the north and to the east of him, so that if they set about turning his position it must be from the Charleroi direction. Hence, his right wing was laid back at an angle to the rest of his line, and the only cavalry which he kept in advance was thrown out to Binche in front of this flank. The rest of the cavalry was on the day of battle drawn in behind the centre of the Army, but as danger began to develop upon the left flank it was sent across in that direction, so that on the morning of the 24th it was at Thulin, at the westward end of the line.

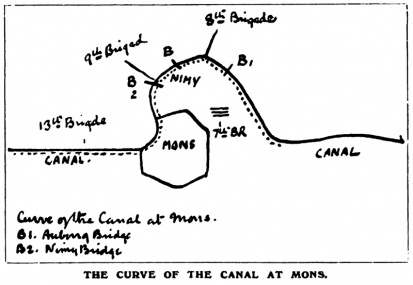

The line of the canal was a most tempting position to defend from Condé to Mons, for it ran as straight as a Roman road across the path of an invader. But it was very different at Mons itself. Here it formed a most awkward loop. A glance at the diagram will show this formation. It was impossible to leave it undefended, and yet troops who held it were evidently subjected to a flanking artillery fire from each side. The canal here was also crossed by at least three substantial road bridges and one railway bridge. This section of the defence was under the immediate direction of General Smith-Dorrien, who at once took steps to prepare a second line of defence, thrown back to the right rear of the town, so that if the canal were forced the British array would remain unbroken. The immediate care of this weak point in the position was committed to General Beauchamp Doran's 8th Brigade, consisting of the 2nd Royal Scots, 2nd Royal Irish, 4th Middlesex, and 1st Gordon Highlanders. On their left, occupying the village of Nimy and the western side of the peninsula, as well as the immediate front of Mons itself, was the 9th Brigade (Shaw's), containing the 4th Royal Fusiliers, the 1st Northumberland Fusiliers, and the 1st Royal Scots Fusiliers, together with the 1st Lincolns. To the left of this brigade, occupying the eastern end of the Mons-Condé line of canal, was Cuthbert's 13th Brigade, containing the 2nd Scottish Borderers, 2nd West Ridings, 1st West Kents, and 2nd Yorkshire Light Infantry. It was on these three brigades, and especially on the 8th and 9th, that the impact of the German army was destined to fall. Beyond them, scattered somewhat thinly along the line of the Mons-Condé Canal from the railway bridge west of St. Ghislain, were the two remaining brigades of the Fifth Division, the 14th (Rolt's) and the 15th (Gleichen's), the latter being in divisional reserve. Still farther to the west the head of the newly-arrived 19th Brigade just touched the canal, and was itself in touch with the French cavalry at Condé. Sundry units of artillery and field hospitals had not yet come up, but otherwise the two corps were complete.

Having reached their ground, the troops, with no realization of immediate danger, proceeded to make-shallow trenches. Their bands had not been brought to the front, but the universal singing from one end of the line to the other showed that the men were in excellent spirits. Cheering news had come in from the cavalry, detachments of which, as already stated, had ridden out as far as Soignies, meeting advance patrols of the enemy and coming back with prisoners and trophies. The guns were drawn up in concealed positions within half a mile of the line of battle. All was now ready, and officers could be seen on every elevation peering northwards through their glasses for the first sign of the enemy. It was a broken country, with large patches of woodland and green spaces between. There were numerous slag heaps from old mines, with here and there a factory and here and there a private dwelling, but the sappers had endeavoured in the short time to clear a field of fire for the infantry. In order to get this field of fire in so closely built a neighbourhood, several of the regiments, such as the West Kents of the 13th and the Cornwalls of the 14th Brigades, had to take their positions across the canal with bridges in their rear. Thrilling with anticipation, the men waited for their own first entrance upon the stupendous drama. They were already weary and footsore, for they had all done at least two days of forced marching, and the burden of the pack, the rifle, and the hundred and fifty rounds per man was no light one. They lay snugly in their trenches under the warm August sun and waited. It was a Sunday, and more than one have recorded in their letters how in that hour of tension their thoughts turned to the old home church and the mellow call of the village bells.

A hovering aeroplane had just slid down with the news that the roads from the north were alive with the advancing Germans, but the estimate of the aviator placed them at two corps and a division of cavalry. This coincided roughly with the accounts brought in by the scouts and, what was more important, with the forecast of General Joffre, Secure in the belief that he was flanked upon one side by the 5th French Army, and on the other by a screen of French cavalry, whilst his front was approached by a force not appreciably larger than his own, General French had no cause for uneasiness. Had his airmen taken a wider sweep to the north and west,[1] or had the French commander among his many pressing preoccupations been able to give an earlier warning to his British colleague, the trenches would, no doubt, have been abandoned before a grey coat had appeared, and the whole Army brought swiftly to a position of strategical safety. Even now, as they waited expectantly for the enemy, a vast steel trap was closing up for their destruction.

Let us take a glance at what was going on over that northern horizon. A day or two earlier, the American Powell had seen something of the mighty right swing which was to end the combat. Invited to a conference with a German general who was pursuing the national policy of soothing the United States until her own turn should come round, Mr. Powell left Brussels and chanced to meet Von Kluck's legions upon their western and southerly trek. He describes with great force the effect upon his mind of those endless grey columns, all flowing in the same direction, double files of infantry on either side of the road, and endless guns, motor-cars, cavalry, and transport between. The men, as he describes them, were all in the prime of life, and equipped with everything which years of forethought could devise. He was dazed and awed by the tremendous procession, its majesty and its self-evident efficiency. It is no wonder, for he was looking at the chosen legions of the most wonderful army that the world had ever seen — an army which represented the last possible word on the material and mechanical side of war. High in the van a Taube aeroplane, like an embodiment of that black eagle which is the fitting emblem of a warlike and rapacious race, pointed the path for the German hordes.

A day or two before, two American correspondents, Mr. Irvin Cobb and Mr. Harding Davis, had seen the same great army as it streamed westwards through Louvain and Brussels. They graphically describe how for three consecutive days and the greater part of three nights they poured past, giving the impression of unconquerable energy and efficiency, young, enthusiastic, wonderfully equipped. "Either we shall go forward or we die. We do not expect to fall hack ever. If the generals would let them, the men would run to Paris instead of walking there." So spoke one of the leaders of that huge invading host, the main part of which was now heading straight for the British line. A second part, unseen and unsuspected, were working round by Tournai to the west, hurrying hard to strike in upon the British flank and rear. The German is a great marcher a well as a great fighter, and the average rate of progress was not less than thirty miles a day.

It was after ten o'clock when scouting cavalry were observed falling back. Then the distant sound of a gun was heard. and a few seconds later a shell burst some hundreds of yards behind the British lines. The British guns one by one roared into action. A cloud of smoke rose along the line of the woods in front from the bursting shrapnel, but nothing could be seen of the German gunners. The defending guns were also well concealed. Here and there, from observation points upon buildings and slag-heaps, the controllers of the batteries were able to indicate targets and register hits unseen by the gunners themselves. The fire grew warmer and warmer as fresh batteries dashed up and unlimbered on either side. The noise was horrible, but no enemy had been seen by the infantry and little damage done.

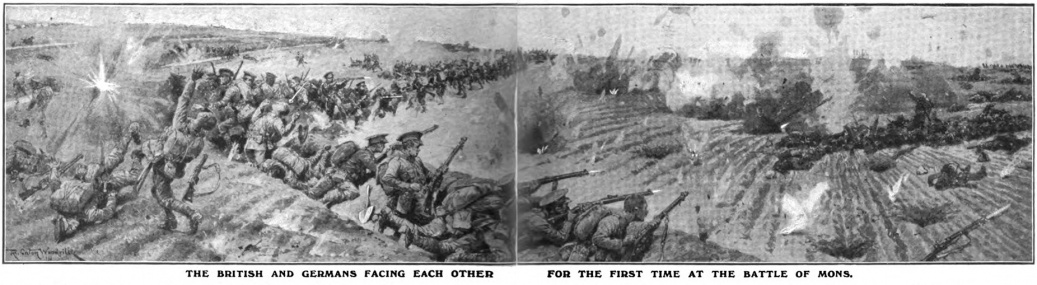

But now an ill-omened bird flew over the British lines. Far aloft across the deep blue sky skimmed the dark Taube, curved, turned, and sailed northwards again. It had marked the shells bursting beyond the trenches. In an instant, by some devilish cantrip of signal or wireless, it had set the range right. A rain of shells roared and crashed along the lines of the shallow trenches. The injuries were not yet numerous, but they were inexpressibly ghastly. Men who had hardly seen worse than a cut finger in their lives gazed with horror at the gross mutilations around them. "One dared not look sideways," said one of them. Stretcher-bearers bent and heaved while wet, limp loans were hoisted upwards by their comrades. Officers gave short, sharp words of encouragement or advice. The minutes seemed very long, and still the shells came raining down. The men shoved the five-fold clips down into their magazines and waited with weary patience. A. senior officer peering over the end of a trench leaned tensely forward and rested his glasses upon the grassy edge. "They're coming!" he whispered to his neighbour, It ran from lip to lip along the line of crouching men. Heads were poked up here and there above the line of broken earth. Soon, in spite of the crashing shells overhead, there was a fringe of peering faces. And there at last in front of them was the German enemy. After all these centuries, Briton and Teuton faced each other at last for the test of battle.

A stylist among letter-writers has described that oncoming swarm as grey clouds drifting over green fields. They had deployed under cover whilst the batteries were preparing their path, and now over an extended front to the north-west of Mons they were breaking out from the woods and coming rapidly onwards. The men fidgeted with their triggers, but no order came to fire. The officers were gazing with professional interest and surprise at the German formations, Were these the tactics of the army which had claimed to be the most scientific in Europe? British observers had seen it in peace-time and had conjectured that it was a screen for some elaborate tactics held up for the day of battle. Yet here they were, advancing in what in old Soudan days used to be described as the twenty-acre formation, against the best riflemen in Europe. It was not even a shoulder to shoulder column, but a mere crowd,shredding out in the front and dense to the rear. There was nothing of the swiftly-weaving lines, the rushes of alternate companies, the twinkle and flicker of a modern attack. It was mediaeval, and yet it was impressive also in its immediate display of numbers and the ponderous insistence of its onward flow.

The men, still fingering their triggers, gazed expectantly at their officers, who measured intently the distance of the approaching swarms. The Germans had already begun to fire in a desultory fashion. Shrapnel was bursting thickly along the head of their column, but they were corning steadily onwards. Suddenly a rolling wave of independent firing broke out from the British position. At some portions of the line the enemy were at eight hundred, at others at one thousand yards. The men, happy in having something definite to do, snuggled down earnestly to their work and fired swiftly but deliberately into the approaching mass. Rifles. machine-guns, and field-pieces were all roaring together, while the incessant crash of the shells overhead added to the infernal uproar. Men lost all sense of time as they thrust clip after clip into their rifles. The German swarms staggered on bravely under that leaden sleet. Then they halted, vacillated, and finally thinned, shredded out, and drifted backwards like a grey fog torn by a gale. The woods absorbed them once again, whilst the rain of shells upon the British trenches became thicker and more deadly.

There was a lull in the infantry attack, and the British peering from their shelters surveyed with a grim satisfaction the patches and smudges of grey which showed the effect of their fire. But the rest was not a long one. With fine courage the German battalions reformed under the shelter of the trees, while fresh troops from the rear pushed forward to stiffen the shaken lines. "Hold your fire!" was the order that ran down the ranks. With the confidence bred of experience, the men waited and still waited, till the very features of the Germans could be distinguished. Then once more the deadly fire rippled down the line, the masses shredded and dissolved, and the fugitives hurried to the woods. Then came the pause under shell fire, and then once again the emergence of the infantry, the attack, the check, and the recoil. Such were the general characteristics of the action at Mons over a large portion of the British line — that portion which extended along the actual course of the canal.

It is not to be supposed, however, that there was a monotony of attack and defence over the whole of the British position. A large part of the force, including the whole of the First Army Corps, was threatened rather than seriously engaged, while the opposite end of the line was also out of the main track of the storm. It heat most dangerously, as had been foreseen, upon the troops to the immediate west and north of Mons, and especially upon those which defended the impossible peninsula formed by the loop of the canal.

The Defence of the Bridges of Nimy

There is a road which runs from Mons due north through the village of Nimy to Jurbise. The defences to the west of this road were in the hands of the 9th Brigade. The 4th Royal Fusiliers, with half the Northumberland Fusiliers, was the particular regiment which held the trenches skirting this part of the peninsula, while the Seats Fusiliers were on the straight canal to the westward. To the east of Ninny are three road bridges — those of Nimy itself, Lock No. 5, and Aubourg Station. All these three bridges were defended by the 4th Middlesex. who had made shallow trenches which commanded them, The Royal Irish were on their immediate right. The field of fire was much interfered with by the mines and buildings which faced them, so that at this point the Germans could get up unobserved to the very front. It has also been already explained that the German artillery could enfilade the peninsula from each side, making the defence most difficult. The first rush of German troops came between eleven and twelve o'clock across the Aubourg Station Bridge (B1 in diagram). It was so screened up to the moment of the advance that neither the rifles nor the machine-guns of the Middlesex could stop it. It is an undoubted fact that this rush was preceded by a great crowd of women and children, through which the leading files of the Germans could hardly he seen, At the same time, or very shortly afterwards, the other two bridges were forced in a similar manner, but the Germans in all three cases as they reached the farther side were unable to make any rapid headway against the British fire, though they made the position untenable for the troops in trenches between the bridges. The whole of the 8th Brigade, supported by the 2nd Irish Rises from McCracken's 7th Brigade, which had been held in reserve, were now fully engaged, covering the retirement of the Middlesex and of the Royal Irish. At some points the firing between the two lines of infantry was across the breadth of a road. Two batteries of the 40th Artillery Brigade, which were facing the German attack at this point, were badly mauled, one of them, the 23rd R.F.A., losing its gun teams. Major Ingham succeeded in reconstituting his equipment and getting his guns away.

It is well to accentuate the fact that though this was the point of the most severe pressure there was never any disorderly retirement, and strong reserves were available had they been needed. The 8th Brigade, at the time of the general strategical withdrawal of the Army, made its arrangements in a methodical fashion, and General Doran kept his hold until after nightfall upon Bois la Haut, which was an elevation to the east of Mans from which the German artillery might have harassed the British retreat, since it commanded all the country to the south. The losses of the brigade had, however, been considerable, amounting to not less than two hundred and fifty each in the case of the 4th Middlesex and of the Royal Irish, many being killed or wounded in the defence, and some cut off in the trenches between the various bridge-heads.

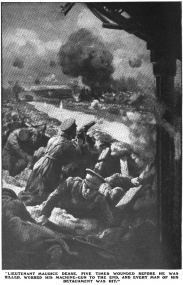

It has already been said that the line of the 4th Royal Fusiliers extended along the western perimeter up to Nimy Road Bridge, where Colonel MacMahon's section ended and that of Colonel Hull, of the Middlesex Regiment, began. To the west of this point was the Nimy Railway Bridge (B2 in diagram), defended also by the 4th Royal Fusiliers. This was held for nearly five hours against an attack of several German battalions. The British artillery was unable to help the defence, as the town of Mons in the rear offered no positions for guns. The Germans were therefore able to push up their guns and knock the trenches to pieces. The defence was continued until the Germans who had crossed to the east were advancing on the flank. Lieutenant Maurice Dease, five times wounded before be was killed, worked his machine-gun to the end, and every man of his detachment was hit. Lieutenant Dease and Private Godley of his party both received' the Victoria Cross, The occupants of one trench, including Lieutenant Smith, who was wounded, were cut off by the rush. Captain Carey commanded the covering company and the retirement was conducted in good order, though Captain Bowden Smith, Lieutenant Mead, and a number of men fell in the movement. Altogether, the Royal Fusiliers lost five officers and about two hundred men in the defence of the bridge, Lieutenant Tower having seven survivors in his platoon of sixty. As the infantry retired a small party of engineers under Captain Theodore Wright endeavoured to destroy, this and other bridges. Lieutenant Day was twice wounded upon the main Nimy Bridge, Lieutenant P. K. Boulnois succeeded in blowing a smaller one up. Corporal Jarvis received the V.C. for his exertions in preparing the Jemappes bridge for destruction to the west of Nimy. Captain Wright, with Sergeant Smith, made an heroic endeavour under terrific fire to detonate the charge, but was wounded and fell into the canal. Lieutenant Holt, a brave young officer of reserve engineers, also lost his life in these operations.

Having held on as long as was possible, the front line of the 9th Brigade fell back upon the prepared position on high ground between Mons and Frameries, where the 107th R.F.A. was entrenched. The 4th Royal Fusiliers passed through Mons and reached the new line in good order and without further loss. The 1st Royal Scots Fusiliers, however, falling back to the same point on a different route (through Flenu), came under heavy machine-gun fire from a high soil heap, losing Captain Rose and a hundred men.

The Holding of the Canal

The falling back of the 8th and 9th Brigades from the Nimy Peninsula had an immediate feet upon Cuthbert's 13th Brigade, which was on their left holding the line up to the railway bridge just east of St. Ghislain. Of this brigade two battalions, the 1st West Kent on the right and the 2nd Scottish Borderers on the left, were in the trenches with the 2nd West Riding and the 2nd Yorkshire Light Infantry in support, having their centre at Boussu. The day began by some losses to the West Kent Regiment, who were probably, apart from cavalry patrols, the first troops to suffer in the great war. A company of the regiment under Captain Lister was sent across the canal early as a support to some advancing cavalry, and was driven in about eleven o'clock with a loss of two officers and about 4 hundred men. From this time onwards the German attacks were easily held, though the German guns were within twelve hundred yards. The situation was changed when it was learned later in the day that the Germans were across to the right and had got as far as Flenu on the flank of the brigade. In view of this advance, General Smith-Dorrien, having no immediate supports, dashed off on a motor to Sir Douglas Haig's headquarters some lour miles distant and got his permission to use Haking's 5th Brigade, which pushed up in time to re-establish the line.

It has been shown that the order of the regiments closely engaged in the front line was, counting from the east, the 4th Middlesex, the 4th Royal Fusiliers, the ist Northumberland Fusiliers, the 1st Vest Rents, and the 2nd Scottish Borderers, the other regiments of these brigades being in reserve. On the left hand or western side of the Scottish Borderers, continuing the line along the canal, one would come upon the front of the 14th Brigade (Roles), which was formed by the 1st Surrey on the right and the and Duke of Cornwall's on the left. The German attack upon this portion of the line began about i p.m., and by 3 p.m. had become so warm that the reserve companies were drawn into the firing line. Thanks to their good work both with rifles and with machine-guns the regiments held their can until about six o'clock in the evening, when the retirement of the troops on their right enabled the Germans to enfilade the right section of the East Surreys at close range. They were ordered to retire, but lost touch with the left section, which remained to the north of the canal where their trench was situated. Captain Benson of this section had been killed and Captain Campbell severely wounded, but the party of one hundred and ten men under Lieutenant Morritt held on most gallantly and made a very fine defence. Being finally surrounded, they endeavoured to cut their way out with cold steel, Lieutenant Ward being killed and Morritt four times wounded in the attempt. Many of the men were killed and wounded and the survivors were taken. Altogether the loss of the regiment was five officers and one hundred and thirty-four men.

On the left of the East Surreys, as already stated, lay the 1st Duke of Cornwall's of the same brigade. About four o'clock in the afternoon the presence of the German outflanking corps first made itself felt. At that hour the Cornwalls were aware of an advance upon their left as well as their front. The Cornwalls drew in across the canal in consequence, and the Germans did not follow them over that evening.

The chief point defended by the 14th Brigade upon August 23rd had been the bridge and main road which crosses the canal between Pommeroeul and Thulin, some eight or nine miles west of Mons. In the evening, when the final order for retreat was given, this bridge was blown up, and the brigade fell back after nightfall as far as Dour, where it slept.

The Fateful Telegram

By the late afternoon the general position was grave, but not critical. The enemy had lost very heavily, while the men in the trenches were, in comparison, unscathed. Here and there, as we have seen, the Germans had obtained a lodgment in the British position. especially at the salient which had always appeared to be impossible to hold, but, on the other hand, the greater part of the Army, including the whole First Corps, had not yet been seriously engaged, and there were reserve brigades in the immediate rear of the fighting line who could be trusted to make good any gap in the ranks before them. The German artillery fire was heavy and well-directed, but the British batteries had held their own. Such was the position when, about 5 p.m., a telegram from General Joffre was put into Sir John French's hand, which must have brought a pang to his heart. From it he learned that all his work had been in vain, and that far from contending for victory he would be fortunate if he saved himself from utter defeat.

There were two pieces of information in this fatal message, and each was disastrous. The first announced that instead of the two German corps whom he had reason to think were in front of him there were four — the third, fourth, seventh, and fourth reserve corps — forming, with the second and fourth cavalry divisions, a force of nearly two hundred thousand men, while the second corps were bringing another forty thousand round his left flank from the direction of Tournai. The second item was even more serious. Instead of being buttressed up with French troops on either side of him, he learned that the Germans had burst the line of the Sambre, and that the French armies on his right were already in full retreat, while nothing substantial lay upon his left. It was a most perilous position. The British force lay exposed and unsupported amid converging foes who far outnumbered it in men and guns. What was the profit of one day of successful defence if the morrow might dawn upon a British Sedan? There was only one course of action, and Sir John decided upon it in the instant, bitter as the decision must have been. The Army must be extricated from the battle and fall back until it resumed touch with its Allies.

But it is no easy matter to disengage so large an army which is actually in action and hard-pressed by a numerous and enterprising enemy. The front was extensive and the lines of retreat were limited. That the operation was carried out in an orderly fashion is a testimony to the skill of the General, the talents of the commanders, and the discipline of the units. If it had been done at once and simultaneously it would certainly have been the signal for a vigorous German advance and a possible disaster. The positions were therefore held, though no efforts were made to retake those points where the enemy had effected a lodgment. There was no possible use in wasting troops in regaining positions which would in no case be held. As dusk fell, a dusk which was lightened by the glare of burning villages, some of the regiments began slowly to draw off to the rear. In the early morning of the 24th the definite order to retire was conveyed to the corps commanders, whilst immediate measures were taken to withdraw the impedimenta and to clear the roads.

Such, in its bare outlines, was the action of Mons upon August 23rd, interesting for its own sake, but more so as being the first clash between the British and German armies. One or two questions call for discussion before the narrative passes on. The most obvious of these is the question of the bridges. Why were they not blown up in the dangerous peninsula? Without having any special information upon the point, one might put forward the speculation that the reason why they were not at once blown up was that the whole of Joffre's advance was an aggressive movement for the relief of Namur, and that the bridges were not destroyed because they would be used in a subsequent advance. It will always be a subject for speculation as to what would have occurred had the battle been fought to a finish. Considering the comparative merits of British and German infantry as shown in many a subsequent encounter, and allowing for the advantage that the defence has over the attack, it is probable that the odds might not have been too great and that Sir John French might have remained master of the field. That, however, is a matter of opinion. What is not a matter of opinion is that the other German armies to the east would have advanced on the heels of the retiring French, that they would have cut the British off from their Allies, and that they would have been hard put to it to reach the coast. Therefore, win or lose, the Army had no possible course open but to retire. The actual losses of the British were not more than three or four thousand, the greater part from the 8th, 9th, and 13th Brigades. There are no means as yet by which the German losses can be taken out from the general returns, but when one considers the repeated advances over the open and the constant breaking of the dense attacking formations, it is impossible that they should have been fewer than from seven to ten thousand men. Each army had for the first time an opportunity of forming a critical estimate of the other. German officers have admitted with soldierly frankness that the efficiency of the British came to them as a revelation, which is not surprising after the assurances that had been made to them. On the other hand, the British bore away a very clear conviction of the excellence of the German artillery and of the plodding bravery of the German infantry, together with a great reassurance as to their own capacity to hold their own at any reasonable odds.

- ↑ An American correspondent, Mr. Harding Davis, actually saw a shattered British aeroplane upon the ground in this region. Its destruction may have been of great strategic importance. This aviator was probably the first British victim in the war.