The British Campaign in France (june 1916)

| << 2/21 The British Campaign in France | The British Campaign in France 4/21 >> |

(The Strand Magazine, june 1916, p. 555)

The British Campaign in France. II. The Battle of Le Cateau is the 3rd article, published in june 1916, in a series of 21 articles written by Arthur Conan Doyle serialized in The Strand Magazine.

Editions

- in The Strand Magazine (june 1916 [UK]) (1 map, 3 photos, 4 ill.)

- in The British Campaign in France and Flanders (1916-1920, Hodder & Stoughton Ltd. [UK])

- in The British Campaign in France and Flanders (1916, George H. Doran Co. [US])

- in The British Campaign in Europe (1914-1918) (november 1928, Geoffrey Bles [UK])

Illustrations

The British Campaign in France (june 1916)

(The Strand Magazine, june 1916, p. 555)

(The Strand Magazine, june 1916, p. 556)

(The Strand Magazine, june 1916, p. 557)

(The Strand Magazine, june 1916, p. 558)

(The Strand Magazine, june 1916, p. 559)

(The Strand Magazine, june 1916, p. 560)

(The Strand Magazine, june 1916, p. 561)

(The Strand Magazine, june 1916, p. 562)

(The Strand Magazine, june 1916, p. 562)

(The Strand Magazine, june 1916, p. 564)

(The Strand Magazine, june 1916, p. 565)

(The Strand Magazine, june 1916, p. 566)

(The Strand Magazine, june 1916, p. 567)

Chapter II. The Battle of Le Cateau (continued)

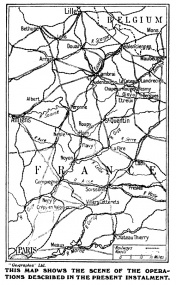

The Fate of the 1st Gordon — Results of the Battle — Exhaustion of the Army — The Destruction of the 2nd Munsters — A Cavalry Fight — The News in Great Britain — The Views of General Joffre — Battery L — The Action of Villars-Cotteret — Reunion of the Army.

It is impossible to doubt that the Germans, in spite of their preponderating numbers, were staggered by the resistance which they had encountered. In no other way can one explain the fact that their pursuit, which for three days had been incessant, should now, at the most critical instant, have eased off. The cavalry and guns staved off the final blow, and the stricken infantry staggered from the field. The strain upon the infantry of the Fifth Division may be gathered from the fact that up to this point they had lost roughly one hundred and forty-three officers, while the Third Division had lost ninety-two and the Fourth seventy. For the time they were disorganized as bodies even while they preserved their moral as individuals.

When extended formations are drawn rapidly in under the conditions of a heavy action it is often impossible to convey the orders to men in outlying positions. Staying in their trenches and unconscious of the departure of their comrades they are sometimes gathered up by the advancing enemy, but more frequently fall into the ranks of some other corps and remain for days or weeks away from their own battalion, turning up long after they have helped to swell some list of casualties. Regiments get intermingled and pour along the roads in a confusion which might suggest a rout, whilst each single soldier is actually doing his best to recover his corps. It is disorganization — but not demoralization.

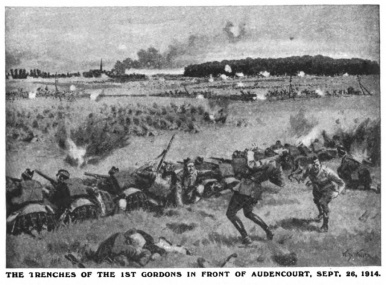

The Fate of the 1st Gordons

It has been remarked above that in the widespread formations of modern battles it is difficult to be sure of the transmission of orders. An illustration of such a danger occurred upon this occasion, which gave rise to an aftermath of battle nearly as disastrous as the battle itself. This was the episode which culminated in the loss of a body of troops, including a large portion of the 1st Gordon Highlanders. This distinguished corps had been engaged with the rest of Beauchamp Doran's Eighth Brigade at Mons and again upon the following day, after which they retreated With the rest of their division. On the evening of the 25th they bivouacked in the village of Audencourt, just south of the Cambrai-Le Cateau highway, and on the morning of the 26th they found themselves defending a line of trenches in front of this village. From nine o'clock the Gordon held their ground against a persistent German attack. About three-thirty an order was given for the regiment to retire. This message only reached one company, which acted upon it, but the messenger was wounded en route, and failed to reach battalion headquarters. Consequently the remainder of the battalion did not retire with the Army, but continued to hold its trenches until long after night-fall, when the enemy in great force had worked round both of its flanks. When it was nearly midnight it became clear to Colonel Neish that he and his men were separated from the Army and that he was surrounded on all sides by the advancing Germans ; at that time the battalion, after supreme exertions for several consecutive days, had been in action for fourteen hours on end. A desperate attempt was made to find some passage through the enemy. The wounded, who were very numerous, were left in the trenches. The transport, machine-guns, and horses had already been destroyed by the incessant artillery fire. The remainder of the regiment made a move towards the south and actually traversed some miles of ground, but found itself hopelessly embedded in Von Kluck's army, and was compelled to surrender. Over a thousand killed, wounded, and missing were the losses in this disastrous incident. Among the officers taken were Colonel Neish and Lieutenant-Colonel Gordon, V.C. The utmost discipline and gallantry were shown throughout by all ranks, but they fell victims to the accident of the lost despatch, and to the difficulty which always exists in keeping touch between units in these days of extended formations. A detachment of the Royal Irish and a handful of the Royal Scots were involved in the misfortune of the Cordons. It must be some consolation to the survivors of these famous come to know that it is more than likely that their resistance in the trenches for so long a period facilitated the safe withdrawal of the rest of the Third Division. Major Leslie Butler, Brigade-Major of the Eighth Brigade, who had made a gallant effort to ride to the Gordons and warn them of the danger of their position, was entangled among the Germans, and only succeeded six days later in regaining the British lines.

Results of the Battle

Such was the perilous, costly, and almost disastrous action of Le Cateau. The loss to the British Army, so far as it can be extracted from complex figures and separated from the other losses of the retreat, amounted to between seven and eight thousand killed, wounded, and missing, while at the time of the action, or in the immediate retreat, a considerable quantity of transport and forty-two field-pieces, mostly in splinters, were abandoned to the enemy. It was an action which could hardly have been avoided, and from which the troops were extricated on better terms than might have been expected. It will always remain an interesting academic question what would have occurred had it been possible for the First Corps to line up with the rest of the Army. The enemy's preponderance of artillery would probably have prevented a British victory, and the strategic position would in any case have made it a barren one, but at least the Germans would have been hard hit and the subsequent retreat more leisurely. As it stood it was an engagement upon which the weaker side can look back without shame or dishonour. One result of it was to give both the Army and the country increased confidence in themselves and their leaders. Sir John French has testified to the splendid qualities shown by the troops, while his whole-hearted tribute to Smith-Dorrien, in which he said, "The saving of the left wing of the Army could never have been accomplished unless a commander of rare and unusual coolness, intrepidity, and determination had been present to personally conduct the operation," will surely be endorsed by history.

It is difficult to exaggerate the strain which had been thrown upon this commander. On him had fallen the immediate direction of the action at Mons ; on him also had been the incessant responsibility of the retreat. He had, as has been shown in the narrative, been hard at work all night upon the eve of the battle ; he superintended that trying engagement, he extricated his forces, and finally motored to St. Quentin in the evening, went on to Noyon, reached it after midnight, and was back with his Army in the morning, encouraging everyone by the magnetism of his presence. It was a very remarkable feat of endurance.

Exhaustion of the Army

Exhausted as the troops were, there could be no halt or rest until they had extricated themselves from the immediate danger. At the last point of human endurance they still staggered on through the evening and the night time, amid roaring thunder and flashing lightning, down the St. Quentin road. Many fell from fatigue, and having fallen continued to sleep in ditches by the roadside oblivious of the racket around them. A number never woke until they found themselves in the hands of the Uhlan patrols. Others slumbered until their corps had disappeared, and then, regaining their senses, joined with other straggling units so as to form bands, which wandered over the country and eventually reached the railway line about Amiens with wondrous Bill Adams tales of personal adventures which in time reached England and gave the impression of complete disaster. But the main body were, as a matter of fact, holding well together, though the units of infantry had become considerably mixed and so reduced that at least four brigades, after less than a week of war, had lost fifty per cent. of their personnel. Many of the men threw away the heavier contents of their packs, and others abandoned the packs themselves, so that the pursuing Germans had every evidence of a rout before their eyes. It was deplorable that equipment should be discarded, but often it was the only possible thing to do, for either the man had to be sacrificed or the pack. Advantage was taken of a forked road to station an officer there who called out, "Third Division right, Fifth Division left," which greatly helped the reorganization. The troops snatched a few hours of rest at St. Quentin, and then in the breaking dawn pushed upon their weary road once more, country carts being in many cases commandeered to carry the lame and often bootless infantry. The paved chaussées, with their uneven stones, knocked the feet to pieces, and caused much distress to the tired men, which was increased by the extreme heat of the weather.

In the case of some of the men the collapse was so complete that it was almost impossible to get them on. Major Tom Bridges, of the 4th Royal Irish Dragoons, being sent to round up and hurry forward two hundred and fifty stragglers at St. Quentin, found them nearly comatose with fatigue. With quick wit he bought a toy drum, and, accompanied by a man with a penny whistle, he fell them in and marched them laughing in all their misery down the high road towards Ham. When he stopped he found that his strange following stopped also, so he was compelled to march and play the whole way to Roupy. Thus by one man's compelling personality two hundred and fifty men were saved for the Army.

Up to now nothing had been seen of the French infantry, and the exposed British force had been hustled and harried by Von Kluck's great army without receiving any substantial support. This was through no want of loyalty, but our gallant Allies were themselves hard pressed. Sir John French had sent urgent representations, especially to General Sordet, the leader of the cavalry operating upon the western side, and he had, as already shown, done what he could to screen Smith-Dorrien's flank. Now at last the retiring Army was coming in touch with those supports which were so badly needed. But before they were reached, on the morning of the nth, the Germans had again driven in the rearguard of the First Corps.

The Destruction of the 2nd Munsters

Some delay in starting had been caused that morning by the fact that only one road was available for the whole of the transport, which had to be sent on in advance. Hence the rearguard was exposed to increased pressure. This rearguard consisted of the First Brigade ; the 2nd Munsters were the right battalion. Then came the 1st Coldstream, the 1st Scots Guards, and the 1st Black Watch in reserve. The front of the Munsters, the regiment principally involved, was from the north of Fesmy to Chapeau Rouge, but Major Charrier, who was in command, finding no French at Bergues, as he had been led to expect, sent B and D companies of Munsters with one troop of the 15th Hussars to hold the cross-roads near that place.

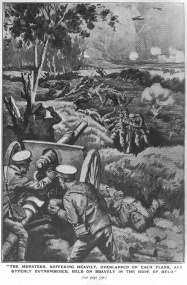

At about twelve-thirty a message reached Major Charrier to the effect that when ordered to retire he should fall back on a certain line and act as flank-guard to the brigade. He was not to withdraw his two companies from Chapeau Rouge until ordered. The Germans were already in force right on the top of the Irishmen, the country being a broken one with high hedges which restricted the field of fire. A section of guns of the 118th R.F.A. were served from the road about fifty yards behind the line of the infantry. A desperate struggle ensued, in the course of which the Munster, suffering heavily, overlapped on each flank, and utterly outnumbered, held on bravely in the hope of help from the rest of the brigade. They did not know that a message had already been dispatched to them to the effect that they should fall back, and that the other regiments had already done so. Still waiting for the orders which never came, they fell back slowly through Fesmy before the attack, and held up at a small village called Etreux, when the Germans cut off their retreat. Mean. while the Brigadier, hearing that the Monsters were in trouble, gave orders that the Cold' stream should reinforce them. It was too late, however. At Oisy Bridge the Guards picked up sixty men, survivors of C Company. It was here at Oisy Bridge that the missing order was delivered at 3 p.m., the cycle orderly having been held up on his way, As there was no longer any sound of firing, the Coldstream and remnant of Munsters retired, being joined some miles hack by an officer and some seventy men. Together with the transport guard this brought the total survivors of that fine regiment to five officers and two hundred and six men. All the rest had fought to the end and were killed, wounded, or captured, after a most desperate resistance in which they were shot down at close quarters, making repeated efforts to pierce the strong German force at Etreux. To their fine work and that of the two lost gum and of a party of the 15th Hussars who covered the retreat it may have been due that the pursuit of the First Corps by the Germans from this moment sensibly relaxed. Nine gallant Irish officers were buried that night in a common grave. Major Charrier was twice wounded, but continued to lead his men until a third bullet struck him dead, and deprived the Army of a soldier whose career promised to be a brilliant one. Among others who fell was Lieutenant Chute, whose masterly handling of a machine-gun stemmed again and again the tide of the German attack. One of the most vivid recollections of the survivors was of this officer lying on his face in six inches of water — for the action was partly fought in tropical min—and declaring that he was having "the time of his life." The moral both of this disaster and that of the Gordon, must be the importance of sending a message in duplicate, or even in triplicate, where the withdrawal of a regiment is concerned. This, no doubt, is a counsel of perfection under practical conditions, but the ideal still remains.

A Cavalry Fight

During the retreat of the First Corps its rear and right flank had been covered by the Fifth Cavalry Brigade (Chetwode). On August 28th the corps was continuing its march towards La Fère and the cavalry found itself near Cerizy. At this point the pursuing German horsemen came into touch with it. At about five in the afternoon three squadrons

of the enemv advanced upon one squadron of the Scots Greys which had the support of J Battery. Being fired at, the Germans dismounted and attempted to advance upon toot, but the fire was so heavy that they could make no progress and their led horses stampeded. They retired, still on foot, followed up by a squadron of the 12th Lancers on their flank. The remainder of the 12th Lancers, supported by the Greys, rode into the dismounted dragoons with sword and lance, killing or wounding nearly all of them. A section of guns had fired over the heads of the British cavalry during the advance into a supporting body of Germans, who retired leaving two hundred of their number behind them. The whole hostile force retreated northwards, while the British cavalry continued to conform to the movements of the First Corps. In this spirited little action the German regiment engaged was, by the irony of fate, the 1st Guard Dragoons, Queen Victoria's Own. The British lost forty-three killed and wounded. Among the dead were Major Swetenham and Captain Michell of the 12th Lancers. Colonel Wormald of the same regiment was wounded. The excited troopers rode back triumphantly between the guns of J Battery, the cavalrymen exchanging cheers with the horse-gunners as they passed, and brandishing their bloodstained weapons.

On the evening before this brisk skirmish, the flank-guards of the British saw a consider-able body of troops in dark clothing upon their left, and shortly afterwards perceived the shell-bunts of a rapid and effective fire over the pursuing German batteries. It was the first contact with the advancing French. These men consisted of the Sixty-first and Sixty-second French Reserve Divisions, and were the van of a considerable army under General D'Amade. From that moment the pursuit relaxed, and the British forces were at last enabled after a week of constant marching, covering sometimes a good thirty miles a day, and four days of continual fighting against extreme odds, to feel that they had reached a zone of comparative quiet.

The News in Great Britain

The German cavalry still followed the Army upon its southerly march, but there was no longer any fear of a disaster, for the main body of the Army was unbroken, and the soldiers were rather exasperated than depressed by their experience. On the Friday and Saturday, however, August 28th and 29th, considerable crowds of stragglers and fugitives, weary and often weaponless, appeared upon the lines of communication, causing the utmost consternation by their stories and their appearance. Few who endured the mental anxiety caused in Great Britain by the messages of Sunday, August 30th, are likely to forget it. The reports gave an enormous stimulus to recruiting, and it is worthy of record and remembrance that, in the dark week which followed before the true situation was clearly discerned, every successive day brought as many recruits to the standards as are usually gained in a year. Such was the rush of men that the authorities, with their many preoccupations, found it very difficult to deal with them. A considerable amount of hardship and discomfort was the result, which was endured with good humour until it could be remedied. It is to be noted in this connection that it was want of arms which held hack the new armies. He who compares the empty arsenals of Britain with the huge extensions of Krupp's, undertaken during the year before the war, will find the final proof as to which Power deliberately planned it.

To return to the fortunes of the men retreating from Le Cateau, the colonels and brigadiers had managed to make order out of what was approaching to chaos on the day that the troops left St. Quentin. The feet of many were so cut and bleeding that they could no longer limp along, so some were packed into a few trains available and others were hoisted on to limbers, guns, wagons, or anything with wheels, some carts being lightened of ammunition or stores to make room for helpless men. In many cases the whole kits of the officers were deliberately sacrificed. Many men were delirious from exhaustion and incapable of understanding an order. By the evening of the 27th the main body of the troops were already fifteen miles south of the Somme river and canal, on the line Nesle — Ham — Flavy. All day there was distant shelling from the pursuers, who sent their artillery freely forward with their cavalry. The Third Division lost by an unlucky shot its chief staff officer, Colonel Boileau.

On the 28th the Army continued its retreat to the line of the Oise near Noyon. Already the troops were reforming, and had largely recovered their spirits, being much reassured by the declarations of the officers that the retreat was strategic to get them in line with the French, and that they would soon turn their faces northwards once more. As an instance of reorganization it was observed that the survivors of a brigade of artillery which had left its horses and guns at Le Cateau still marched together as a single disciplined unit among the infantry. All day the enemy's horse artillery, cavalry, and motor-infantry hung on the skirts of the British, but were unable to make much impression. The work of the staff was wonderful, for it is on record that many of them had not averaged two hours' sleep in the twenty-four for over a week, and still they remained the clear and efficient wain of the Army.

On the next day, the 29th, the remainder of the Army got across the Oise, but the enemy's advance was so close that the British cavalry was continually engaged. Gough's Third Cavalry Brigade made several charges in the neighbourhood of Plessis, losing a number of men but stalling off the pursuit and dispersing the famous Uhlans of the Guard. On this day General Fulteney and his staff arrived to take command of the Third Army Corps, which still consisted only of the Fourth Division (Snow) and the semi-independent Nineteenth Infantry Brigade, which was now commanded by Colonel Ward, of the 1st Middlesex, General Drummond having been injured on the 26th. It was nearly three weeks later before the Third Corps was made complete.

The Views of General Joffre

There had been, as already mentioned, a French advance of four corps in the St. Quentin direction, which fought a brave covering action, and so helped to relieve the pressure upon the British. It cannot be denied that there was a feeling among the latter that they had been unduly exposed, being placed in so advanced a position and having their flank stripped suddenly bare in the presence of the main German army. General Joffre must have recognized that this feeling existed and that it was not unreasonable, for he came to a meeting on this day at the old Napoleonic Palace at Compiègne, at which Sir John French, with Generals Haig, Smith-Dorrien, and Allenby, was present. It was an assemblage of weary, overwrought men, and yet of men who had strength enough of mind and sufficient sense of justice to realize that whatever weight had been thrown upon them, there was even more upon the great French engineer whose spirit hovered over the whole line from Verdun to Amiens. Each man left the room more confident of the immediate future. Shortly afterwards Joffre issued his kindly recognition o f the work done by his Allies, admitting in the most handsome fashion that the flank of the long French line of armies had been saved by the hard fighting and self-sacrifice of the British Army. On August 30th, the whole Army having crossed the Oise, the bridges over that river were destroyed, an operation which was performed under a heavy shell-fire, and cost the lives of several sapper officers and men. No words can exaggerate what the Army owed to Wilson's sappers of the 56th and 57th Field Companies and 3rd Signal Company, as also to Tulloch's, of the 17th and 59th Companies R. E. and 5th Signal Company, whose work was incessant, fearless, and splendid.

The Army continued to fall back on the line of the Aisne, the general direction being almost east and west through Crecy-en-Valois. The aeroplanes, which had conducted a fine service during the whole of the operations, reported that the enemy was still coming rapidly on, and streaming southwards in the Compiègne direction. That they were in touch was shown in dramatic fashion upon the early morning of September 1st. The epic in question deserves to be told somewhat fully, as being one of those incidents which are mere details in the history of a campaign, and yet may live as permanent inspirations in the life of an army.

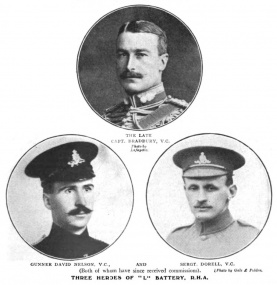

Battery L.

The First Cavalry Brigade, greatly exhausted after screening the retreat so long. was encamped near Nery, to the south of Compiègne, the bivouac being a somewhat extended one. Two units were close to each other and to the brigade headquarters of General Briggs. These were a squadron of the 2nd Dragoon Guards (the Bays) and L Battery of Horse Artillery. Réveillé was at four o'clock, and shortly after that hour both troopers and gunners were busy in leading their horses to water. It was a misty morning, and, peering through the haze, an officer perceived that from the top of a low hill about seven hundred yards away three mounted men were looking down upon them. They were the observation officers of two four-gun German batteries. Before the British could realize the situation the guns dashed up and came into action with shrapnel at point-blank range. The whole eight poured their fire into the disordered bivouac before them. The slaughter and confusion were horrible.

Numbers of the horses and men were killed or wounded and three of the guns were dismounted. It was a most complete surprise and promised to be an absolute disaster. It is at such moments that the grand power of disciplined valour comes to bring order out of chaos. Everything combined to make defence difficult — the chilling hour of the morning, the suddenness of the attack, its appalling severity, and the immediate loss of guns and men. A sunken road ran behind the British position, and from the edge of this the dismounted cavalrymen brought their rifles and their machine-gun into action. They suffered heavily from the pelting gusts of shrapnel. Young Captain de Crespigny, the gallant cadet of a gallant family, and many other good men were beaten down by it. The sole hope lay in the guns. Three were utterly disabled. There was a rush of officers and men to bring the other three into action. Sclater-Booth, the major of the battery, and one lieutenant were already down. Captain Bradbury took command and cheered on the men. Two of the guns were at once put out of action, no all united to work the one that remained. What followed was Homeric. Lieutenant Gifford in rushing forward was hit in four places. Bradbury's leg was shattered, but he lay beside the trail encouraging the others and giving his directions. Lieutenant Mundy, standing wide as observation officer, was mortally wounded. The limber could not be got alongside and the shell had to be man-handled. In bringing it up Lieutenant Campbell was shot. Immediately afterwards another shell burst over the gun, killed the heroic Bradbury, and wounded Sergeant Dorell, Driver Osborne, and Gunners Nelson and Derbyshire, the only remaining men. But the fight went on. The bleeding men served the gun no long as they could more Osborne and Derbyshire crawling over with the shells while Nelson loaded and Dad laid. Osborne and Derbyshire fainted free loss of blood and lay between limber and gun. But the fight went on. Dorell and Nelson, wounded and exhausted, crouched behind the shield of the thirteen-pounder and kept up an incessant fire. Now it was the the amazing fact became visible that all the devotion had not been in vain. The dusts of Bays on the edge of the sunken road into out into a cheer; which was taken up by the staff, who, with General Briggs himself, had come into the firing-line. Several of de German pieces had gone out of action. The dying gun had wrought terrible damage, had the Maxim of the Bays in the hands a Lieutenant Lamb. Some at least of its opponents had been silenced before the two brave gunner, could do no more, for their strength had gone with their blood. Not only had the situation been saved, but victory had been assured.

About eight in the morning news of the perilous situation had reached the Nineteenth Brigade. The 1st Middlesex, under Colonel Rowley, sat hurried forward, followed by the 1st Scottish Rifles. Marching rapidly upon the firing, after the good old maxim, the Middlesex found themselves in a position to command the German batteries. After two minutes of rapid fire it was seen that the enemy had left their guns. The Middlesex then advanced, losing their machine-gun officer, Lieutenant Jeffard, from the fire of the German escort. The guns were captured, two of them still loaded. About a doses German gunners lay dead or wounded round them. Twenty-five of the escort were captured, as was an ambulance with some further prisoners a mile in the rear. The cavalry endeavoured to follow up the success, but soon found themselves m the presence of superior forces. New wheels and new wheelers were found for the injured guns, and Battery L came intact out of action — intact save for the brave acolytes who should serve her no more. Bradbury, Nelson, and Dorell had the Victoria Cross, and never was it better earned. The battery itself was recalled to England to refit and the guns were changed for new ones. It is safe to say that for many a long year these shrapnel-dinted thirteen pounders will serve as a monument of one of those deeds which, by their self-sacrifice and nobility, do something to mitigate the squalors and horrors of war.

The success was gained at the cost of many valuable lives. Not only had the personnel of the battery been destroyed, but the Bays lost heavily, and there were some casualties among the rest of the brigade who had some up in support. The 5th Dragoon Guards had fifty or sixty wounded, and lost its admirable commander, Colonel Ansell, who was shot down in a flanking movement which he had initiated. Major Cawley, of the Staff, also fell. The total British loss was not far short of five hundred killed and wounded, but the Germans lost heavily also, and were compelled to abandon their guns.

The Action of Villars-Cotteret

The German advance guards were particularly active upon this day, September 1st, the anniversary of Sedan. Although the Soissons Bridge had been destroyed they had possession of another at Vic, and over this they poured in pursuit of the First Corps, overtaking about 8 a.m. near Villars-Cotteret the rearguard, consisting of the Irish Guards and the and Coldstream. The whole of the Fourth Guards Brigade was drawn into the fight, which resolved itself into a huge rifle duel amid thick woods, Scott-Kerr, their Brigadier, riding up and down the firing line. The Guards retired slowly upon the Sixth Infantry Brigade (Davies), which was aided by Lushington's Forty-first Brigade of Artillery, just south of Pisseleux. The Germans had brought up many guns, but could make no further progress, and the British position was held until 6 p.m., when the rearguard closed up with the rest of the Army [1]. Lushington's guns had fought with no infantry in front of them, and it was a matter of great difficulty in the end to get them off, but it was accomplished by some very brilliant work under an infernal fire. After this sharp action, in which Colonel Morris of the Irish Guards lost his life, the retreat of the First Army Corps was not seriously interfered with. The losses at that date in this corps amounted to eighty-one officers and two thousand one hundred and eighty of all ranks.

So much attention is naturally drawn to the Second Army Corps, which both at Mons and at Le Cateau had endured most of the actual fighting, that there is some danger of the remarkable retreat effected by the First Corps having less than its fair share of appreciation. The actual fighting was the least of the difficulties. The danger of one or both flanks being exposed, the great mobility of the enemy, the indifferent and limited roads, the want of rest, the difficulty of getting food cooked, the consequent absolute exhaustion of the men, and the mental depression combined to make it an operation of a most trying character, throwing an enormous strain upon the judgment and energy of General Haig, who so successfully brought his men intact and fit for service into a zone of safety.

Reunion of the Army

On the night of September 1st, the First and Second Army Corps were in touch once more at Bet; and were on the move again by 2 a.m. upon the and. On this morning the German advance was curiously interlocked with the British rear, and four German guns were picked up by the cavalry near Ermenonville. They are supposed to have been the remaining guns of the force which attacked Battery L at Nery. The movements of the troops during the day were much impeded by the French refugees, who thronged every road in their flight before the German terror, In spite of these obstructions, the rearward services of the Army — supply columns, ammunition columns, and medical transport — were well conducted, and the admiration of all independent observers. The work of all these departments had been greatly complicated by the fact that, as the Channel ports were now practically undefended and German troops, making towards the coast, had cut the main Calais - Boulogne line at Amiens, the base had been moved farther south from Havre to St. Nantire, which meant shifting seventy thousand tons of stores and changing all arrangements. In spite of this the supplies were admirable. It may safely be said that if there is one officer more than another for whom the whole British Army felt a glow of gratitude, it was for the Chief of the Commissariat, who saw that the fighting man was never without his rations.

A difficult move lay in front of the Army which was to cross the Marne, involving a flank march in the face of the enemy. A retirement was still part of the general French scheme of defence, and the British Army had to conform to it, though it was exultantly whispered from officer to sergeant and from sergeant to private that the turn of the tide was nearly due. On this day it was first observed that the Germans, instead of pushing forward, were swinging across to the east in the direction of Château-Thierry. This made the task of the British a more easy one, and before evening they were south of the Marne and bad blown up the bridges. The movement of the Germans brought them down to the river, but at a point some ten miles east of the British position. They were reported to be crossing the river at La Ferté, and Sir John French continued to fall back towards the Seine, moving after sundown, as the heat had been for some days very exhausting. The troops halted in the neighbourhood of Presles, and were cheered by the arrival of some small drafts, numbering about two thousand, a first instalment towards refilling the great gaps in the ranks, which at this date could not have been less than from twelve to fifteen thousand officers and men. Here for a moment this narrative may be broken, since it has taken the Army to the farthest point of its retreat and reached that moment of advance for which every officer and man, from Sir John French to the drummer-boys, was eagerly waiting. With their left flank resting upon the outer forts of Paris, the British troops had finally ended a retreat which will surely live in military history as a remarkable example of an army retaining its cohesion and moral in the presence of an overpowering adversary, who could never either cut them off or break in their rearguard. The British Army is a small force when compared with the giants of the Continent, but when tried by this supreme test it is not mere national complacency for us to claim that it lived up to its own highest traditions. "It was not to forts of steel and concrete that the Allies owed their strength," said a German historian, writing of this phase of the war, "but to the magnificent qualities of the British Army." We desire no compliments at the expense of our brothers-in-arms, nor would they be just, but at least so generous a sentence as this may be taken as an advance from that contemptuous view of the British Army with which the campaign had begun.

Before finally leaving the consideration of his historical retreat, where a small army successfully shook itself clear from the long and close pursuit of a remarkably gallant, mobile, and numerous enemy, it may be helpful to give a chronology of the events, that the reader may see their relation to each other.

| HAIG'S 1st CORPS. | SMITH-DORRIEN'S 2nd CORPS. |

|---|---|

| August 22nd. | |

| Get into position to the east of Mons, covering the line Mons-Bray. | Get into position to the west of Mons. covering the line Mons-Conde. |

| August 23rd. | |

| Artillery engagement, but no severe attack. Ordered to retreat in conformity with 2nd Corps. | Strongly attacked by Von Kluck's army. Ordered to abandon position and fall back. |

| August 24th. | |

| Retreat with no serious molestation upon Bavaye. Here, the two Corps diverged and did not meet again till they reached Betz upon September 1st. | Retreat followed up by the Germans. Severe rearguard actions at Dour, Wasmes, Fremeries. Corps shook itself clear and fell back on Bavaye. |

| August 25th. | |

| Marching all day. Overtaken in evening at Landrecies and Maroilles by the German pursuit. Sharp fighting. | Marching all day. Reinforced by 9th Division. Continual rearguard action becoming more serious towards evening, when Cambrai-Le Gateau line was reached. |

| August 26th. | |

| Rearguard actions in morning. Marching south all day, halting at the Venerolles line. | Battle of Le Cateau. German pursuit stalled off at heavy cost of men and guns. Retreat on St. Quentin. |

| August 27th. | |

| Rearguard action in which Munsters lost heavily. Marching south all day. | Marching south. Reach the line Nesli-Ham-Flavy. |

| August 28th. | |

| Cavalry actions to stop German pursuit. Marching south on La Fère. | Marching south, making for the line of the Oise near Noyon. Light rearguard skirmishes. |

| August 29th, 30th, and 31th. | |

| Marching on the line of the Aisne, almost east and west. | Crossed Oise. Cavalry continually engaged. General direction through Crecy-en-Valois. |

| September 1st. | |

| Sharp action at Nery with German vanguard. Later in the day considerable infantry action at Villars-Cotteret. Unite at Betz. | Retreat upon Paris continued. Late this night the two Corps unite once more at Betz. |

| September 2nd. | |

| Crossed the Marne and began to fall back on the Seine. Halted near Presles. | Crossed the Marne and began to fall back on the Seine. |

- ↑ British losses are often hard to estimate where the field has not been held. In this instance, through the energy of Lord Robert Cecil and Mr. Ian Malcolm, the dead guardsmen were exhumed and their remains reburied with pious care. There were ninety-eight bodies, including Colonel Morris and Captain Tisdall of the Irish, Lieutenant Lambton (Coldstream), and Lieutenant Cecil (Grenadiers).