Ronald A. Knox

Ronald Arbuthnott Knox (17 february 1888 - 24 august 1957) was an English priest who is famous for being the precursor of the Sherlockiana with the publication in 1912 of his article Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes.

Biography

Ronald Arbuthnott Knox was born in 1888 in England at Leicester where his father was an Anglican bishop (like his grandfather). He studied at Eton and Oxford (Balliol College) where he received numerous academic awards and degrees in 1910. He was ordained an Anglican priest in 1912 and was also appointed chaplain at Trinity College, Oxford University. He resigned, however, in 1917 because the study and reflection led him to convert to Roman Catholicism, much to the despair of his father. He explained the reasons for this move in Apologia (1917). The following year, he was ordained a Catholic priest. In the following years, he wrote a few religious texts and he relaxed by reading crime fiction. Wielding satire and parody master, before the Second World War, he sowed inadvertently panic in England, the day when the radio gave an account of a revolution in London he had invented from scratch. In 1936, he served with the Pope as domestic prelate. In 1939, he retired from office in order to devote his time to a new translation of the Vulgate, which was published in several volumes from 1944 to 1950. His commentary of the New Testament was also published in 1950. The father Knox has written many very scholar religious works. A book of his sermons was published and are also as serious.

In 1925, he began his career as an author of detective novels by writing The Viaduct Murder. Distinguished by its satirical twist, this is perhaps the most remarkable of his books. In 1927, he invented an investigator for an insurance company, Miles Bredon, which will be the hero of several novels. The father Knox has also contributed to various collective work on Mystery theme. But eventually, crime novels are what is less interesting in the work of Ronald A. Knox, because the narrative is slow and unimaginative. However, they have had some success at the time of their release, and if Knox put an end to his career as an author of detective novels, it's not because his stories did not please the readers, but because his bishop asked him to cease "an unworthy practice for a Catholic priest."

The two most important contributions of Knox in crime fiction have in fact nothing to do with fiction. There is first the forerunner of what became our favorite pastime, the Sherlockiana since the publication of an article ironically entitled Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes, published by Blue Book in 1912. The text was read for the first time in public on 10 March 1911 at the Bodley Club of Merton College, then three days later at the Gryphon Club of Trinity College, both in Oxford, and then was published by W. H. L. Watson. Bishop Knox then made the golden rules of the author of detective story in the introduction to the Knox-edited collection of the Best Detective Stories of 1928-29. The list prohibits the use of supernatural effects, unknown poisons science and, more generally, invites the respect of a certain fair play vis-à-vis the reader on delivery clues.

In 1947, he published in The Strand Magazine a sherlockian pastiche The Apocryphal Sherlock Holmes: The Adventure of the First Class Carriage.

Photos

-

Ronald A. Knox

-

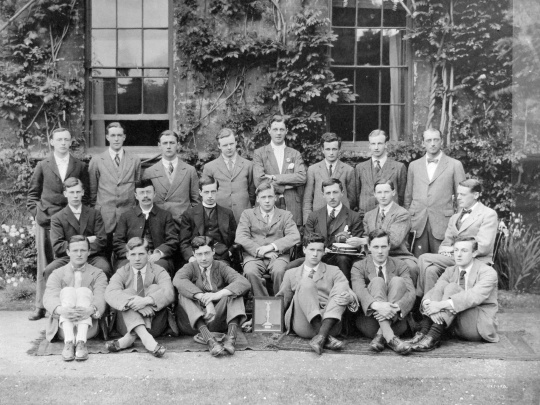

The Gryphon Club (1912)

-

Ronald Knox and Sherlock Holmes: The Origins of Sherlockian Studies (Gasogene Books, 2011)

-

From Piff-Pouff to Backnecke: The Full Story (The Baker Street Journal, 2010)

The Ten Rules of (Golden Age) Detective Fiction

He was also known for his decalogue "The Ten Rules of (Golden Age) Detective Fiction" as a preface for "Best Detective Stories of 1928-29" :

- The criminal must be someone mentioned in the early part of the story, but must not be anyone whose thoughts the reader has been allowed to follow.

- All supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course.

- Not more than one secret room or passage is allowable.

- No hitherto undiscovered poisons may be used, nor any appliance which will need a long scientific explanation at the end.

- No Chinaman must figure in the story.

- No accident must ever help the detective, nor must he ever have an unaccountable intuition which proves to be right.

- The detective must not himself commit the crime.

- The detective must not light on any clues which are not instantly produced for the inspection of the reader.

- The stupid friend of the detective, the Watson, must not conceal any thoughts which pass through his mind; his intelligence must be slightly, but very slightly, below that of the average reader.

- Twin brothers, and doubles generally, must not appear unless we have been duly prepared for them.