The British Campaign in France (september 1916)

| << 5/21 The British Campaign in France | The British Campaign in France 7/21 >> |

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 314)

The British Campaign in France. V. The La Bassée-Armentières Operations is the 6th article, published in september 1916, in a series of 21 articles written by Arthur Conan Doyle serialized in The Strand Magazine.

Editions

- in The Strand Magazine (september 1916 [UK]) (2 map, 4 ill.)

- in Everybody's Magazine (december 1916 [UK]) as Two Empires at Grips

- in The British Campaign in France and Flanders (1916-1920, Hodder & Stoughton Ltd. [UK])

- in The British Campaign in France and Flanders (1916, George H. Doran Co. [US])

- in The British Campaign in Europe (1914-1918) (november 1928, Geoffrey Bles [UK])

Illustrations

-

-

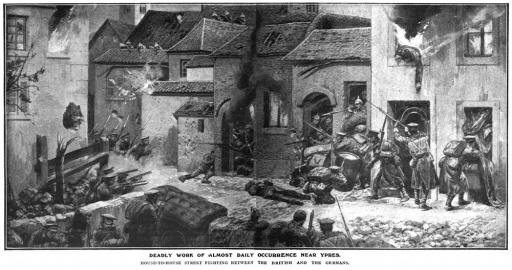

Deadly work of almost daily occurence near Ypres.

-

Our Indian troops working shoulder to shoulder with the thin Khaki line.

-

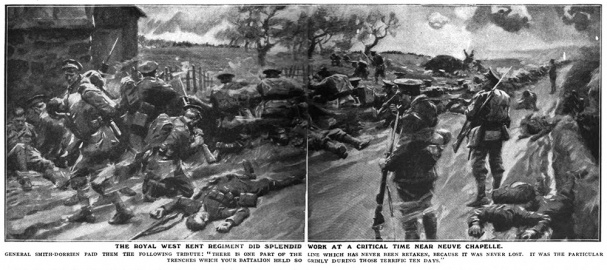

The Royal West Kent Regiment did splendid work at a critical time near Neuve Chapelle.

-

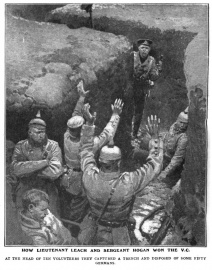

How Lieutenant Leach and Sergeant Hogan won the V.C.

-

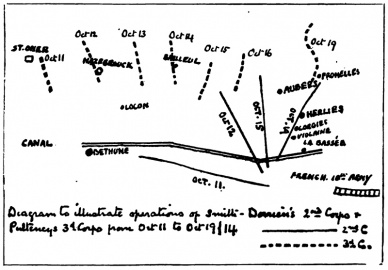

The scene of the operations described in the present instalment.

The British Campaign in France (september 1916)

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 314)

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 315)

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 316)

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 317)

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 318)

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 319)

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 320)

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 321)

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 322)

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 323)

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 324)

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 325)

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 326)

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 327)

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 328)

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 329)

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 330)

(The Strand Magazine, september 1916, p. 331)

Chapter V. The La Bassée-Armentières Operations

(From October 11th to October 31st.)

The Great Battle Line — Advance of the Second Corps — Death of General Hamilton — The Farthest Point — Fate of the 2nd Royal Irish — The Third Corps — Exhausted Troops — First Fight of Neuve Chapelle — The Indians Take Over — The Lancers at Warneton — Pulteney's Operations — Action of Le Gheir.

In accordance with the new plans, the great transference began upon October 3rd. It was an exceedingly difficult problem, since an army of more than a hundred thousand men had to be gradually extricated by night from trenches which were often not more than a hundred yards from the enemy, while a second army of equal numbers had to be substituted in its place. Any alarm to the. Germans might have been fatal, since a vigorous night attack in the middle of the operation would have been difficult to resist, and even an artillery bombardment must have caused great loss of life. The work of the Staff in this campaign has been worthy of the regimental officers and of the men. Everything went without a hitch. The Second Cavalry Division (Gough's) went first, followed immediately by the First (De Lisle's). Then the infantry was withdrawn, the Second Corps being the vanguard ; the Third Corps followed, and the First was the last to leave. The Second Corps began to clear from its trenches on October 3rd-4th, and were ready for action on the Aire-Bethune line upon October with. The Third Corps was very little behind it, and the First had reached the new battle-ground upon the 19th. Cavalry went by road ; infantry marched part of the way, trained part of the way, and did the last lap very often in motor-buses. One way or another the men were got across, the Aisne trenches were left for ever, and a new phase of the war had begun. From the chalky uplands and the wooded slopes there is a sudden change to immense plains of clay, with slow, meandering, ditch-like streams, and all the hideous features of a great coal-field added to the drab monotony of Nature. No scenes could be more different, but the same great issue of history and the same old problem of trench and rifle were finding their slow solution upon each. The stalemate of the Aisne was for the moment set aside and once again we had reverted to the old position where the ardent Germans declared, "This way we shall come," and the Allies, "Not a mile, save over our bodies."

The Great Battle Line

The narrator is here faced with a considerable difficulty in his attempt to adhere closely to truth and yet to make his narrative intelligible to the lay reader. We stand upon the edge of a great battle. If all the operations which centred at Ypres, but which extend to the Yser Canal upon t h e north and to La Bassée at the south, be grouped into one episode it becomes the greatest clash of arms ever seen up to that hour upon the globe, involving a casualty list — Belgian, French, British, and German — which could by no means be computed as under two hundred and fifty thousand, and probably over three hundred thousand men. It was fought, however, over an irregular line which is roughly forty miles from north to south, while it lasted, in its active form, from October 12th to November 20th before it settled down to the inevitable siege stage. Thus both in time and in space it presents difficulties which make a concentrated, connected, and intelligible narrative no easy task. In order to attempt this, it is necessary first to give a general idea of what the British Army, in conjunction with its Allies, was endeavouring to do, and, secondly, to show how the operations affected each corps in its turn.

During the operations of the Aisne the French had extended the Allied line far to the north in the hope of outflanking the Germans. The Tenth French Army, under General Foch, formed the extreme left of this vast manoeuvre, and it was supported on its left by the French cavalry. The German right had lengthened out, however, to meet every fresh extension of the French, and their cavalry had been sufficiently numerous and alert to prevent the French cavalry from getting round. Numerous skirmishes had ended in no definite result. It was at this period that it occurred, as already stated, to Sir John French that to bring the whole British Army round to the north of the line would both shorten very materially his line of communications and would prolong the line to an extent which might enable him to turn the German flank and make their whole position impossible. General Joffre having endorsed these views, Sir John took the steps which we have already seen. The British movement was, therefore, at the outset an aggressive one. How it became defensive as new factors intruded themselves, and as a result of the fall of Antwerp, will be shown at a later stage of this account.

As the Second Corps arrived first upon the scene it will be proper to begin with some account of its doings from October 12th, when it went into action, until the end of the month, when it found itself brought to a standstill by superior forces and placed upon the defensive. The doings of the Third Corps during the same period will be inter-woven with those of the Second, since they were in close co-operation ; and, finally, the fortunes of the First Corps will be followed and the relation shown between its doings and those of the newly-arrived Seventh Division, which had fallen back from the vicinity of Antwerp and turned at bay near Ypres upon the pursuing Germans. Coming from different directions, all these various bodies were destined to be formed into one line, cemented together by their own dismounted cavalry and by French reinforcements, so as to lay an unbroken breakwater beyond the great German flood.

Advance of the Second Corps

The task of the Second Corps was to. get into touch with the left flank of the Tenth French Army in the vicinity of La Bassée, and then to wheel round its own left so as to turn the position of those Germans who were facing our Allies. The line of the Bethune-Lille road was to be the hinge, connecting the two armies and marking the turning-point for the British. On the 11th Gough's Second Cavalry Division was clearing the woods in front of the Aire-Bethune Canal, which marked the line of the Second Corps. By evening Gough had connected up the Third Division of the Second Corps with the Sixth Division of the Third Corps, which was already at Hazebrouck. On the 12th Hamilton's Third Division crossed the canal, followed by the Fifth Division, with the exception of the Thirteenth Brigade, which remained to the south of it. Both divisions advanced more or less north before swinging round to almost due east in their outflanking movement. The rough diagram gives an idea of the point from which they started and the positions reached at various dates before they came to an equilibrium. There were many weary stages, however, between the outset and the fulfilment, and the final results were destined to be barren as compared with the exertions and the losses involved. None the less it was, as it proved, an essential part of that great operation by which the British — with the help of their good allies — checked the German advance upon Calais in October and November, even as they had helped to head them off from Paris in August and September. During these four months the little British Army, far from being negligible, as some critics had foretold would be the case in a Continental war, was absolutely vital in holding the Allied line and taking the edge off the hacking German sword.

The Third Corps, which had detrained at St. Omer awl moved to Hazebrouck, was intended to move pari passu with the Second, prolonging its line to the north. The First and Second British Cavalry Divisions, now under the command of De Lisle and of Gough, with Allenby as chief, had a rôle of their own to play, and the space between the Second and Third Corps was now filled up by a French Cavalry Division under Conneau, a whole-hearted soldier always ready to respond to any call. There was no strong opposition yet in front of the Third Corps, but General Pulteney moved rapidly forwards, brushedaside all resistance,and seized the town of Bailleul. A German position in front of the town, held by cavalry and infantry without guns, was rushed by a rapid advance of Haldane's Tenth Infantry Brigade, the 2nd Seaforths particularly distinguishing themselves, though the 1st Warwicks and 1st Irish Fusiliers had also a good many losses, the Irishmen clearing the trenches to the old cry of "Faugh-a-Ballagh!" which has sounded so often upon battlefields of old. The Tenth Brigade was on the left of the corps, and in touch with the Second Cavalry Division to the north. The whole action, with its swift advance and moderate 'losses, was a fine vindication of British infantry tactics. On the evening of October 15th the Third Corps had crossed the Lys, and on the 18th they extended from Warneton in the north to almost within touch of the position of the Second Corps at Aubers upon the same date.

The country in which the Second Corps was advancing upon October 12th was an extraordinarily difficult one, which offered many advantages to the defence over the attack. It was so flat that it was impossible to find places for artillery observation, and it was intersected with canals, high hedgerows, and dykes, which formed ready-made trenches. The Germans were at first not in strength, and consisted for the most part of dismounted cavalry drawn from four divisions, but from this time onwards there was a constant fresh accession of infantry and guns. They disputed with great skill and energy every position which could be defended, and the British advance during the day, though steady, was necessarily slow. Every hamlet, hedgerow, and stream meant a separate skirmish. The troops continually closed ranks, advanced, extended, and attacked from morning to night, sleeping where they had last fought. There was nothing that could be called a serious engagement, and yet the losses — almost entirely from the Third Division—amounted to three hundred for the day, the heaviest sufferers being the 2nd Royal Scots.

On the next day, the 13th, the corps swung round its left so as to develop the turning movement already described. Its front of advance was about eight miles, and it met resistance which made all progress difficult. Again the Eighth Brigade, especially the Royal Scots and 4th Middlesex, lost heavily. The principal fighting, however, fell late in the evening upon the Fifteenth Brigade (Gleichen's), who were on the right of the line and in touch with the Bethune Canal. The enemy, whose line of resistance had been considerably thickened by the addition of several battalions of Jaeger and part of the Fourteenth Corps, made a spirited counter-attack on this portion of the advance. The 1st Cheshires and the 1st Bedfords were roughly handled and driven back, with the result that the 1st Dorsets, who were stationed at a bridge over the canal (Pont Fixe), found their flank exposed and sustained heavy losses, amounting to three hundred men, including Major Roper. Colonel Bols, of the same regiment, enjoyed one crowded hour of glorious life, for he was wounded, captured, and escaped all on the same evening. It was in this action also that Major Vandeleur was wounded and captured. [1] A section of guns which was involved in the same dilemma as the Dorsets had to be abandoned after every gunner had fallen. The Fifteenth Brigade was compelled to fall back for half a mile and entrench itself for the night. On the left the Seventh Brigade (McCracken's) had some eighty casualties in crossing the Lys, and a detachment of Northumberland Fusiliers, who covered their left flank, came under machine-gun fire, which struck down their adjutant, Captain Herbert, and a number of men. Altogether the losses on this day amounted to about seven hundred men.

Death of General Hamilton

On the 14th the Second Corps continued its slow advance in the same direction. Upon this day the Third Division sustained a grievous loss in the shape of its commander, General Sir Hubert Hamilton, who was standing conversing with the quiet nonchalance which was characteristic of him, when a shell burst above him and a shrapnel bullet struck him on the temple, killing him at once. He was a grand commander, beloved by his men, and destined for the highest had he lived. He was buried that night after dark in a village churchyard. There was an artillery attack by the Germans during the service, and the group of silent officers, weary from the fighting line, who stood with bowed heads round the grave, could hardly hear the words of the chaplain for the whiz and crash of the shells. It was a proper ending for a soldier.

His division was temporarily taken over by General Colin Mackenzie. On this date the Thirteenth Brigade, on the south of the canal, was relieved by French troops, so that henceforward all the British were to the north. For the three preceding days this brigade had done heavy work, the pressure of the enemy falling particularly upon the 2nd Scottish Borderers, who lost Major Allen and a number of other officers and men.

The 15th was a day of spirited advance, the Third Division offering sacrifice in the old warrior fashion to the shade of its dead leader. Guns were brought up into the infantry line and the enemy was smashed out of entrenched positions and loopholed villages in spite of a most manful resistance. The soldiers carried long planks with them and threw them over the dykes on their advance. Mile after mile the Germans were pushed back, until they were driven off the high road which connects Estaires with La Bassée. The 1st-Northumberland and 4th Royal Fusiliers of the Ninth Brigade, and the 2nd Royal Scots and 4th Middlesex of the Eighth, particularly distinguished themselves in this day of hard fighting. By the night of the 15th the corps had lost ninety officers and two thousand men in the four days, the disproportionate number of officers being due to the broken nature of the fighting, which necessitated the constant leading of small detachments. The German resistance continued to be admirable.

On the 16th the slow wheeling movement of the Second Corps went steadily though slowly forward, meeting always the same stubborn resistance. The British were losing heavily by the incessant fighting, but so were the Germans, and it was becoming a question which could stand punishment longest. In the evening the Third Division was brought to a stand by the village of Aubers, which was found to be strongly held. The Fifth Division was instructed to mark time upon the right, so as to form the pivot upon which all the rest of the corps could swing round in their advance on La Bassée. At this date the Third Corps was no great distance to the north, and the First Corps was detraining from the Aisne. As the Seventh Division with Byng's Third Cavalry Division were reported to be in touch with the other forces in the north, the concentration of the British Army was approaching a successful issue. The weather up to now during all the operations which have been described was wet and misty, limiting the use of artillery and entirely preventing that of aircraft.

The Farthest Point

On the 17th the advance was resumed and was destined to reach the extreme point which it attained for many a long laborious month. This was the village of Herlies, north-east of La Bassée, which was attacked in the evening by Shaw's Ninth Brigade, and was carried in the dusk at the point of the bayonet by the 1st Lincolns and the 4th Royal Fusiliers, The Seventh Brigade was less fortunate at the adjoining village of lilies, where they failed to make a lodgment, but the French cavalry on 'the extreme left, with the help of the 2nd Royal Irish, captured Fromelles, The Fifth Division also came forward a little, the right flank still on the canal, but the left bending round so as to get to the north of La Bassée. The day's casualties amounted to two hundred men, including eight officers.

On the 18th, Sir Charles Ferguson, who had done good work with the Army from the first gunshot of the war, was promoted to a higher rank and the command of the Fifth Division passed over to General Morland, Thus both divisions of the Second Corps changed their commanders within a week. On this date the infantry of Roles Fourteenth Brigade, with some of Cuthbert's Thirteenth Brigade, were within eight hundred yards of Bassée, but found it so strongly held that it could not be entered, the Scottish Borderers losing heavily in a very gallant advance. The village of lilies also remained impregnable, being strongly entrenched and loopholed. Shaw's Ninth Brigade took some of the trenches, but found their left flank exposed, so had to withdraw nearly half a mile and to entrench. In this little action the 1st Royal Scots Fusiliers bore the brunt of the fighting and the losses. Eight officers and nearly two hundred men of this regiment were killed or wounded. A fresh German division came into action this day and their artillery was stronger, so that the prospects of future advance were not particularly encouraging. Our own artillery was worked very hard, being overmatched and yet undefeatable. The strain both upon the men and the officers was great, and the observation officers showed great daring and tenacity.

Fate of the 2nd Royal Irish

On the 19th neither the Third nor the Fifth Divisions made any appreciable progress, but one British regiment was heavily engaged and added a fresh record to its ancient roll of valour. This was the 2nd Royal Irish under Major Daniell, who attacked the village of Le Filly rather forward from the British left in co-operation with the French cavalry. The Irish infantry charged over eight hundred yards of clear ground, carried the village by storm, and entrenched themselves within it. This advance and charge, which was carried out with the precision of an Aldershot field day, although one hundred and thirty men fell during the movement, is said by experienced spectators to have been a great feat of arms. The 20th saw a strong counter-attack of the Germans, and by the evening their two flanks had lapped round Le Pilly, pushing off on the one side the French cavalry of Conneau, and on the other a too small detachment of the Royal Fusiliers who were flanking the Irishmen. All day the defenders of Le Pilly were subjected to a terrific shell-fire, and all attempts to get messages to them were unavailing. In the evening they were surrounded, and only two or three men of the battalion were ever seen again. The gallant Daniell fell, and it is on record that his last audible words were a command to fix bayonets and fight to the end, the cartridges of the battalion being at that time exhausted. A German officer engaged in this attack and subsequently taken prisoner has deposed that three German battalions attacked the Royal Irish, one in front and one on each flank, after they had been heavily bombarded in enfilade. Several hundred Irish dead and wounded were taken out of the main trench. The original attack and the subsequent defence constitute one of the feats of arms of the war.

There was now ample evidence that the Germans had received large reinforcements and that their line was too strong to be forced. The whole object and character of the operations assumed, therefore, a new aspect. The Second and Third Corps had swung round, describing an angle of ninety degrees with its pivot upon the right at the La Bassée Canal, and by this movement it had succeeded in placing itself upon the flank of the German force which faced the Tenth French Army. But there was now no longer any flank, for the German reinforcements had enabled them to prolong their line and so to turn the action into a frontal attack by the British. Such an attack in modem warfare can only hope for success when carried out by greatly superior numbers, whereas the Germans were now stronger than their assailants, having been joined by one division of the Seventh Corps, a brigade of the Third Corps, and the whole of the Fourteenth Corps, part of which had already been engaged.

The Third Corps

The increased pressure was being felt by the Third Corps on the Lys, as well as by the Second to the south of them ; indeed, as only a few miles intervened between the two, they may be regarded as one for these operations. We have seen that, having taken the town of Bailleul, Pulteney's Corps had established itself across the Lys, and occupied a line from Warneton to Radinghem upon October 18th. The latter village had been taken on that day by the Sixteenth Brigade in an action in which the 1st Buffs and 2nd Lancashires and Yorkshires lost heavily. Pulteney was now strongly attacked, and there was a movement of the Germans on October 10th as if to turn his right and slip in between the two British corps. The action was carried on into the 2 1st, the enemy still showing considerable energy and strength. The chief German advance during the day was north of La Bassée. It came upon the village of Lorgies, which was the point where the South Lancashires, of McCracken's Seventh Brigade, forming the extreme right of the Third Division, were in touch with the East Surreys and Duke of Cornwall's of Rolt's Fourteenth Brigade, forming the extreme left of the Fifth Division. It is necessary to join one's flats carefully in the presence of the Germans, for they are sharp critics of such matters. In this instance a sudden attack near Illies drove in a portion of the 2nd South Lancashires, a regiment which has a magnificent record for the campaign. This attack also destroyed the greater part of a company of the 1st Cornwalls in support. An ugly gap was left in the line, but the remainder of the Cornwalls, with the help of a company of the 1st West Kents and the ever-constant artillery, filled it up during the rest of the day, and the 2nd Yorkshire Light Infantry took it over the same night, the Cornishmen retiring with heavy losses but a great deal of compensating glory. The temporary gap in the line also exposed the right flank of the 3rd Worcesters, who were next to the South Lancashires. They lost heavily in killed and wounded, their colonel, Stuart, being among the latter, though his injury did not prevent him from remaining in the battle line. Apart from this action at Lorgies, the Nineteenth Brigade (Gordon's), upon the flank of Pulteney's Corps, sustained a very heavy attack, being driven back for some distance. It had been ordered to occupy Fromelles, and so close the gap which existed at that time between the left of the Second and the right of the Third Corps, situated respectively at Aubers and Radinghem. The chief fighting occurred at the village of Le Maisnil, close to Fromelles. This village was occupied by the 2nd Argylls and half the 1st Middlesex, but they were driven out by a severe shell-fire followed by an infantry advance. The brigade fell back in good order, the regiments engaged having lost about three hundred men. They took up a position on the right of the Sixteenth Infantry Brigade at La Boutillerie, and there they remained until November 17th, one severe attack falling upon them on October 29th, which is described under that date.

On the morning of October 22nd the Germans, still very numerous and full of fight, made a determined attack upon the Fifth Division, occupying the village of Violaines, close to La Bassée. The village was held by the 1st Cheshires, who, for the second time in this campaign, found themselves in a terribly difficult position. The Cheshires inflicted heavy losses upon the stormers with rifle-fire, but were at last driven out, involving in their retirement the 1st Dorsets, who had left their own trenches in order to help them. Both regiments, but especially the Cheshires, had grievous losses, in casualties and prisoners. On advancing in pursuit the Germans were strongly counter-attacked by the 2nd Manchesters and the 1st Cornwalls, supported by the 3rd Worcesters, who, by their steady fire, brought them to a standstill, but were unable to recover the ground that had been lost, though the Cornwalls, who had been fighting with hardly a pause for forty-eight hours, succeeded in capturing one of their machine-guns. In the night the British withdrew their line in accordance with the general re-arrangement to be described. Some rear-guard stragglers at break of day had the amusing experience of seeing the Germans making a valiant and very noisy attack upon the abandoned and empty trenches.

On this date, October 22nd, not only had Smith-Dorrien experienced this hold-up upon his right flank, but his left flank had become more vulnerable, because the French had been heavily attacked at Fromelles, and had been driven out of that village. An equilibrium had been established between attack and defence, and the position of the Aisne was beginning to appear once again upon the edge of Flanders. General Smith-Dorrien, feeling that any substantial advance was no longer to be hoped for under the existing conditions, marked down and occupied a strong defensive position, from Givenchy on the south to Fanquissart on the north. This involved a retirement of the whole corps during the night for a distance of from one to two miles, but it gave a connected position with a clear field of fire. At the same time the general situation was greatly strengthened by the arrival at the front of the Lahore Division of the Indian Army under General Watkis. These fine troops were placed in reserve behind the Second Corps in the neighbourhood of Locon.

Exhausted Troops

It is well to remember at this point what Smith-Dorrien's troops had already endured during the two months that the campaign had lasted. Taking the strength of the corps at thirty-seven thousand men, they had lost, roughly, ten thousand men in August, ten thousand in September, and five thousand up to date in these actions of October. It is certain that far less than fifty per cent. of the original officers and men were still with the Colours, and drafts can never fully restore the unity and spirit of a homogeneous regiment, where every man knows his company leaders and his platoon. In addition to this they had now fought night and day for nearly a fortnight, with broken and insufficient sleep, laying down their rifles to pick up their spades, and then once again exchanging spade for rifle, while soaked to the skin with incessant fogs and rain, and exposed to that most harassing form of fighting, where every clump and hedgerow covers an enemy. They were so exhausted that they could hardly be woken up to fight. To say that they were now nearing the end of their strength and badly in need of a rest is but to say that they were mortal men and had reached the physical limits that mortality must impose.

The French cavalry divisions acting as links between Pulteney and Smith-Dorrien were now relieved by the Eighth (Jullundur) Indian Infantry Brigade, containing the 1st Manchesters, 59th (Scinde) Rifles, 40th Pathans, and 47th Sikhs. It may be remarked that each Indian brigade is made up of three Indian and one British battalion. This change was effected upon October 24th, a date which was marked by no particular military event save that the Third Division lost for a time the services of General Beauchamp Doran, who returned to England. General Doran had done great service in leading what was perhaps the most hard-worked brigade in a hard-worked division. General Bowes took over the command of the Eighth Infantry Brigade.

On the night of October 24th determined attacks were made upon the trenches of the Second Corps at the Bois de Biez, near Neuve Chapelle, but were beaten off with heavy loss to the enemy, who had massed together twelve battalions in order to rush a particular part of the position. The main attack fell upon the 1st Wiltshires and the 2nd Royal Irish Rifles, belonging to McCracken's Seventh Brigade, and also upon the 15th Sikhs of the Sirhind Brigade, who seem to have been the first Indians to be seriously engaged, having nearly two hundred casualties, The Eighth Brigade were also involved in the fight. The Germans had some temporary success in the centre of the. trenches of the Third Division, where, in the darkness, they pushed back the 1st Gordon Highlanders, who lost very heavily. As the Highlanders fell back, the 2nd Royal Scots, upon their right, swung back its flank companies, covered the retirement, and then, straightening their ranks again, flung the Germans, at the point of their bayonets, out of the trenches. It was one of several remarkable feats which this fine battalion has performed in the war. Next morning the captured trenches were banded over to the care of the 4th Middlesex

First Fight of Neuve Chapelle

The pressure upon the exhausted troops was extreme upon this day, for a very severe attack was made also upon the Fifth Division, holding the right of the line. The soldiers, as already shown, were in no condition for great exertions, and yet, after their wont, they rose grandly to the occasion. The important village of Givenchy, destined for many a long month to form the advanced post upon the right of the Army, was held by the 1st Norfolks under Colonel Ballard, who defied all efforts of the enemy to dislodge them. Nevertheless, the situation was critical and difficult for both divisions, and the only available support, the 1st Manchesters from the Lahore Division, were pushed up into the fighting line and found themselves instantly engaged in the neighbourhood of Givenchy. It was dreadful weather, the trenches a quagmire, and the rifle-bolts often clogged with the mud. On the 26th Sir John French, realizing how great was the task with which the weary corps was faced, sent up two batteries of 4'7 guns, which soon lessened the volume of the German artillery attack. At the same time General Maistre, of the Twenty-first French Corps, sent two of his batteries and two of his battalions. Thus strengthened, there was no further immediate anxiety as to the line being broken, especially as upon the 26th Marshal French, carefully playing card after card from his not over-strong hand, placed the Second Cavalry Division and three more Indian battalions in reserve to Smith-Dorrien's corps. The German advance had defied all efforts of the enemy to dislodge them. Nevertheless, the situation was critical and difficult for both divisions, and the only available support, the 1st Manchesters from the Lahore Division, were pushed up into the fighting line and found themselves instantly engaged in the neighbourhood of Givenchy. It was dreadful weather, the trenches a quagmire, and the rifle-bolts often clogged with the mud. On the 26th Sir John French, realizing how great was the task with which the weary corps was faced, sent up two batteries of 4'7 guns, which soon lessened the volume of the German artillery attack. At the same time General Maistre, of the Twenty-first French Corps, sent two of his batteries and two of his battalions. Thus strengthened, there was no further immediate anxiety as to the line being broken, especially as upon the 26th Marshal French, carefully playing card after card from his not over-strong hand, placed the Second Cavalry Division and three more Indian battalions in reserve to Smith-Dorrien's corps. The German advance had also been attacked and roughly handled. The indomitable Smith-Dorrien was determined to have his village, however, and in the neighbouring French cavalry commander, General Conneau, he found a worthy 40 colleague who was ready to throw his last man into the venture. The Second Cavalry, now under General Mullets (formerly Colonel), of the 4th Dragoon Guard s, was also ready, as our cavalry has always been ready, to spring in as a makeweight when the balance trembled. The German losses were known to have been tremendous, and it was hoped that the force of their attack was spent. On the 28th the assault was renewed, prefaced by a strong artillery preparation, but again it was brought to a standstill. The 47th Sikhs fought magnificently from loopholed house to house, as did the Indian sappers and miners, while the cavalry showed themselves to be admirable infantry at a pinch, but the defence was still too strong and the losses too severe, though at one time Colonel McMahon, of the Fusiliers, had seized the whole-north end of the village.

Some sixty officers and one thousand five hundred men had fallen in the day's venture, including seventy of the cavalry. The night fell with Neuve Chapelle still in the hands of the enemy, and the British troops to the north, east, and west of it in a semicircle. The Fourteenth Brigade, coming up after dark, found the West Kent Regiment reduced to two officers and one hundred and fifty men, and the Yorkshire Light Infantry at about the same strength, still holding on to positions which had been committed to them three days before. The conduct of these two grand regiments upon that and the previous days excited the admiration of everyone, for, isolated from their comrades, they had beaten off a long succession of infantry attacks and had been enfiladed by a most severe shell-fire. Second-Lieutenant White, with a still younger officer named Russell, formed the whole staff of officers of the West Kents. Major Buckle, Captain Legard, and many others having been killed or wounded, Penny and Crossley, the two sergeant-majors, did great work, and the men were splendid. These shire regiments, raised from the very soil of England, reflect most nearly her national qualities, and in their stolid invincibility form a fitting framework of a great national army. Speaking to the West Dents at a later date, General Smith-Dorrien said : "There is one part of the line which has never been retaken, because it was never lost. It was the particular trenches which your battalion held so grimly during those terrific ten days."

The determined efforts were not spent in vain, for the Germans would not bide the other brunt. Early on the 29th the British patrols found that Neuve Chapelle had been evacuated by the enemy, who must have lost several thousand men in its capture and fine subsequent defence. In this village fighting the British were much handicapped at this time by the want of high explosive shells to destroy the houses. The enemy's artillery made it impossible for the British to occupy it, and some time later it reverted to the Germans once more, being occupied by the Seventh Westphalian Corps. It was made an exceedingly strong advance position by the Germans, but it was reoccupied by the British Fourth Corps (Rawlinson's) and the Indian Corps (Willcocks') upon March 10th in an assault which lasted three days, and involved a loss of twelve thousand men to the attackers and at least as many to the defenders. This battle will be described among the operations of the spring of 1915, but it is mentioned now to show how immutable were the lines between these dates.

The southern or La Bassée end of the line had also been attacked upon the 28th and 29th, arid the 2nd Manchesters driven from their trenches, which they instantly regained, killing seventy of the enemy and taking a number of prisoners. It was in this action that Lieutenant Leach and Sergeant Hogan earned the V.C., capturing a trench at the head of ten volunteers and disposing of some fifty Germans. Morland's Fifth Division had several other skirmishes during these days, in which the Duke of Cornwall's, Manchesters, and 1st Devons, who had taken the place of the Suffolks in the Fourteenth Brigade, were chiefly engaged. The Devons had come late, but they had been constantly engaged and their losses were already as great as the others. In each case the general line was held, though the price was often severe. At this period General Wing took command of the Third Division instead of General Mackenzie — invalided home — the third divisional change within a fortnight.

The Indians Take Over

The arduous month of October was now drawing to a close, and so it was hoped were the labours of the weary Second Corps. Already, on the top of all their previous casualties, they had lost three hundred and sixty officers and eight thousand two hundred men since on October 12th they had crossed the La Bassée Canal. The spirit of the men was unimpaired for the most part — indeed, it seemed often to rise with the emergency — but the thinning of the ranks, the incessant labour, and the want of sleep had produced extreme physical exhaustion. Upon October 29th it was determined to take them out of the front line and give them the rest which they so badly needed. With this end in view, Sir James Willcocks' Indian Corps was moved to the front, and it was gradually substituted for the attenuated regiments of the Second Corps in the first row of trenches. The greater part of the corps was drawn out of the line, leaving two brigades and most of the artillery behind to support the Indians. That the latter would have some hard work was speedily apparent, as upon this very day the 8th Gurkhas were driven out of their trenches. With the support of a British battalion, however, and of Vaughan's Indian Rifles they were soon recovered, though Colonel Venner of the latter corps fell in the attack. This warfare of unseen enemies and enormous explosions was new to the gallant Indians, but they soon accommodated themselves to it, and moderated the imprudent gallantry which exposed them at first to unnecessary loss.

Here, at the end of October, we may leave the Second Corps. It was speedily apparent that their services were too essential to be spared, and that their rest would be a very nominal one. The Third Corps will he treated presently. They did admirably all that came to them to do, but they were so placed that both flanks were covered by British troops, and they were less exposed to pressure than the others. The month closed with this corps and the Indians holding a line which extended north and south for about twenty miles from Givenchy and Festubert in the south to Warneton in the north. We will return to the operations in this region, but must turn back a fortnight or so in order to follow the very critical and important events which had been proceeding in the north. Before doing so it would be well to see what had befallen the cavalry, which, when last mentioned, had, upon October nth, cleared the woods in front of the Second Corps and connected it up with the right wing of the Third Corps. This was carried out by Gough's Second Cavalry Division, which was joined next day by De Lisle's First Division, the whole under General Allenby. This considerable force moved north upon October 12th and 13th, pushing back a light fringe of the enemy and having one brisk skirmish at Mont des Cats, a small hill, crowned by a monastery, where the body of the Crown Prince of Hesse was picked up after the action. Still fighting its way, the cavalry moved north to Berthen and then turned eastwards towards the Lys to explore the strength of the enemy and the passages of the river in that direction. Late at night upon the 14th General de Lisle, scouting northwards upon a motor-car, met Prince Alexander of Teck coming southwards, the first contact with the isolated Seventh Division.

The Lancers at Warneton

On the night of the 16th an attempt was made upon Warneton, where the Germans had a bridge over the river, but the village was too strongly held. The Third Cavalry Brigade was engaged in the enterprise, and the 16th Lancers was the particular regiment upon whom it fell. The main street of the village was traversed by a barricade and the houses loopholed. The Germans were driven by the dismounted troopers, led by Major Campbell, from the first barricade, but took refuge behind a second one, where they were strongly reinforced. The village had been set on fire, and the fighting went on by the glare of the flames. When the order for retirement was at last given it was found that several wounded Lancers had been left close to the German barricade. The fire having died down, three of the Lancers — Sergeant Glasgow, Corporal Boyton, and Corporal Chapman — stole down the dark side of the street in their stockinged feet and carried some of their comrades off under the very noses of the Germans. Many, however, had to be left behind. It is impossible for cavalry to be pushful and efficient without taking constant risks which must occasionally materialize. The general effect of the cavalry operations was to reconnoitre thoroughly all the west side of the river and to show that the enemy were in firm possession of the eastern bank.

From this time onwards until the end of the month the cavalry were engaged in carrying on the north and south line of defensive trenches, which, beginning with the right of the Second Corps (now replaced by Indians) at Givenchy, was prolonged by the Third Corps as far as Frelingham. There the cavalry took it up and carried it through Comines to Wervicq, following the bend of the river. These lines were at once strongly attacked, but the dismounted troopers held their positions. On October 22nd the 12th Lancers were heavily assaulted, but with the aid of an enfilading fire from the 5th Lancers drove off the enemy. That evening saw four more attacks, all of them repulsed, but so serious that Indian troops were brought up to support the cavalry. Every day brought its attack until they culminated in the great and critical fight from October 30th to November 2nd, which will be described later. The line was held, though with some loss of ground and occasional set-backs, until November 2nd, when considerable French reinforcements arrived upon the scene. It is a fact that for all these weeks the position which was held in the face of incessant attack by two weak cavalry divisions should have been, and eventually were, held by two army corps.

Pulteney's Operations

It is necessary now to briefly sketch the movements of the Third Corps (Pulteney's). Its presence upon the left flank of the Second Corps, and the fact that it he'd every attack that came against it, made it a vital factor in the operations. It is true that, having staunch British forces upon each flank, its position was always less precarious than either of the two corps which held the southern and northern extremities of the line, for without any disparagement to our Allies, who have shown themselves to be the bravest of the brave, it is evident that we can depend more upon troops who are under the same command, and whose movements can . be certainly coordinated. At the same time, if the Third Corps had less to do, it can at least say that whatever did come to it was excellently well done, and that it preserved its line throughout. Its units were extended over some twelve miles of country, and it was partly astride of the River Lys, so that here as elsewhere there was constant demand upon the vigilance and staunchness of officers and men. On October 20th a very severe attack fell upon the 2nd Sherwood Foresters, who held the most advanced trenches of Congreve's Eighteenth Brigade. They were nearly overwhelmed by the violence of the German artillery fire, and were enfiladed on each side by infantry and machine-guns. The 2nd Durhams came up in reinforcement, but the Foresters had already sustained grievous losses in casualties and prisoners, the regiment being reduced from nine hundred to two hundred and fifty in a single day. The Durhams also lost heavily. On this same day, the 20th, the 2nd Leinsters, of the Seventeenth Brigade, were also driven from their trenches and suffered severely.

Action of Le Gheir

On October 21st the Germans crossed the River Lys in considerable force, and upon the morning of the 22nd they succeeded in occupying the village of Le Gheir upon the western side, thus threatening to outflank the positions of the Second Cavalry Division to the north. In their advance in the early morning of the 22nd they stormed the trenches held by the 2nd Inniskilling Fusiliers, this regiment enduring considerable losses. The trenches on the right were held by the 1st Royal Lancasters and 2nd Lancashire Fusiliers. These two regiments were at once ordered by General Anley, of the Twelfth Brigade, to initiate a counter-attack under the lead of Colonel Butler. Anley himself, who is a hard-bitten soldier of much Egyptian fighting, moved forward with the 1st East Lancashires, while General Hunter-Weston, the indefatigable blower-up of railway lines in South Africa, supported the counterattack with the Somerset Light Infantry and the 1st East Lancashires. The latter regiment, under Colonel Lawrence, passed through a wood and reached such a position that they were able to enfilade the Germans in the open, causing them very heavy losses. The action was a brilliant success. The positions lost were re-occupied and the enemy severely punished, over a thousand Germans being killed or wounded, while three hundred were taken prisoners. These belonged to the 104th and 179th Saxon regiments. It was a strange turn of fate which, after fifteen hundred years, brought tribesmen who had wandered up the course of the Elbe face to face in deadly strife with fellow-tribesmen who had passed over the sea to Britain. It is worth remarking and remembering that they are the one section of the German race who in this war have shown that bravery is not necessarily accompanied by coarseness and brutality.

On October 25th the attacks became most severe upon the line of Williams' Sixteenth Brigade, and on that night the trenches of the 1st Leicesters were raked by so heavy a gunfire that they were found to be untenable, the regiment losing three hundred and fifty men. The line both of the Sixteenth and of the Eighteenth Brigades was drawn back for some little distance. There was a lull after this, broken upon the 29th, when Gordon's Nineteenth Brigade, the isolated unit which had fought sturdily from the beginning of the war and was now on the right of the Third Corps, was attacked with great violence by six fresh battalions — heavy odds against the four weak regiments which composed the British Brigade. The 1st Middlesex Regiment was driven from part of its trenches, but came back with a rush, helped by their comrades of the 2nd Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. The Germans were thrown out .of the captured trenches, forty were made prisoners, and two hundred were slain. This attack was made by the 223rd and 224th Regiments of a German reserve corps. It was not repeated.

On the 30th another sharp action occurred near St. Yves, when Hunter-Weston's Eleventh Brigade was momentarily pierced after dusk by a German rush, which broke through a gap in the Hampshires. The Somerset Light Infantry, under Major Prowse, came back upon them and the trenches were regained. In all such actions it is to be remembered that where a mass of men can suddenly be directed against scattered trenches which will only hold a few, it is no difficult matter to carry them, but at once the conditions reverse themselves and the defenders mass their supports, who can usually turn the intruders out once more.

This brings the general record of the doings of the Third Corps down to the end of October, the date on which we cease the account of the operations at the southern end of the British line.

We turn from this diffuse and difficult story, with its ever-varying positions and units, to the great epic of the north, which will Le inseparably united for ever with the name of Ypres.

Chapter VI. The First Battle of Ypres

(Up to the Action of Gheluvelt, October 31st.)

The Seventh Division — Its Peculiar Excellence — Its Difficult Position — A Deadly Ordeal.

The Seventh Division

It has already been seen that the Seventh Division (Capper's), being the first half of Rawlinson's Fourth Army Corps, had retired south and west after the unsuccessful attempt to relieve Antwerp. It was made up as follows:—

- DIVISION VII. — Gen. Capper.

- 20th Infantry Brigade — Gen. Ruggles-Brise.

- lst Grenadier Guards.

- 2nd Scots Guards.

- 2nd Border Regiment.

- 2nd Gordon Highlanders.

- 21st Infantry Brigade. — Gen. Watts.

- 2nd Bedfords.

- 2nd Yorks.

- 2nd Wilts.

- 2nd Scots Fusiliers.

- 22nd Infantry Brigade — Gen. Lawford.

- 1st South Staffords.

- 2nd Warwicks.

- 2nd Queen's West Surrey. 1st Welsh Fusiliers.

- Artillery.

- XXII. Brigade R.F.A.

- XXXV. Brigade R.F.A.

- 3rd R.G.A.

- 111th R.G.A.

- 112th R.G.A.

- Engineers.

- 54, 55, F. Co.

- 7 Signal Co.

- Divisional Cavalry.

- Northumberland Yeomanry.

Its Peculiar Excellence

It is not too much to say that in an army where every division had done so well no single one was composed of such fine material as the Seventh. The reason was that the regiments composing it had all been drawn from foreign garrison duty, and consisted largely of soldiers of from three to seven years' standing, with a minimum of reservists. In less than a month from the day when this grand division of eighteen thousand men went into action its infantry had been nearly annihilated, but the details of its glorious destruction furnish one more vivid page of British military achievement. We lost a noble division and gained a glorious record.

The Third Cavalry Division under General Byng was attached to the Seventh Division, and joined up with it at Roulers upon October 13th. It consisted of:—

- 6th Cavalry Brigade — Gen. Makings.

- 3rd Dragoon Guards.

- 1st Royals.

- 10th Hussars.

- C Battery, R.H.A.

- 7th Cavalry Brigade — Gen. Kavanagh.

- 1st Life Guards.

- 1st Horse Guards.

- 2nd Life Guards.

- K Battery, R.H.A.

The First Army Corps not having yet come up from the Aisne, these troops were used to cover the British position from the north, the infantry lying from Zandvoorde through Gheluvelt to Zonnebeke, and the cavalry on their left from Zonnebeke to Langemarck from October 16th onwards. It was decided by Sir John French that it was necessary to get possession of the town of Menin, some distance to the east of the general British line, but very important because the chief bridge by means of which the Germans were receiving their ever-growing reinforcements was there. The Seventh Division was ordered accordingly to advance upon this town, its left flank, being covered by the Third Cavalry Division.

Its Difficult Position

The position was a dangerous one. It has already been stated that the pause on the Aisne may not have been unwelcome to the Germans, as they were preparing reserve formations which might be suddenly thrown against some chosen spot in the Allied line. They had the equipment and arms for at least another two hundred and fifty thousand men, and that number of drilled men were immediately available, some being Landwehr who had passed through the ranks, and others young formations which had been preparing when war broke out. Together. they formed no less than five new army corps, available for the extreme western front, more numerous than the whole British and Belgian armies combined. This considerable force, secretly assembled and moved rapidly across Belgium, was now striking the north of the Allied line, debouching not only over the river at Menin, but also through Courtrai, Iseghem, and Roulers. It consisted of the 22nd, 23rd, 24th, 26th, and 27th reserve corps. Of these the 22nd, and later the 24th, followed the Belgians to the line of the Yser, but the other corps were all available for an attack upon the flank of that British line which was faced by formidable opponents — a line which extended over thirty miles and had already been forced into a defensive attitude. That was the situation when the Seventh Division faced round near Ypres. Sir John French was doing all that he could to support it, and Sir Douglas Haig was speeding up his army corps from the Aisne to take his place to the north of Ypres, but there were some days during which Rawlinson's men were in the face of a force six or seven times larger than themselves.

Upon October 16th and 17th the division had advanced from Ypres and occupied the line already mentioned, the right centre of which rested about the ninth kilometre on the Ypres-Menin road, the order of the brigades from the north being Twenty-two, Twenty-one, and Twenty. On October 18th the division wheeled its left forward. As the infantry advanced, the covering cavalry soon became aware of grave menace from Roulers and Courtrai in the north. A large German force was evidently striking-down on to the left flank of the advance. The division was engaged all along the line, for the Twentieth Brigade upon the right had a brisk skirmish, while the Twenty-first Brigade in the centre was also under fire, which came especially heavily upon the 2nd Bedfords, who had numerous casualties. About ten o'clock on the morning of the 19th the pressure from the north increased, and the Seventh Cavalry Brigade was driven in, though it held its own with great resolution for some time, helped by the fine work of K Battery, R.H.A. The Sixth Cavalry Brigade was held up in front, while the danger on the flank grew more apparent as the hours passed. In these circumstances General Rawlinson, fortified in his opinion by the precise reports of his airmen as to the strength of the enemy upon his left, came to the conclusion that a further advance would place him in a difficult position. He therefore dropped back to his original line. There can be little doubt that, if he had persevered in the original plan, his force would have been in extreme danger. As it was, before he could get it back the 1st Welsh Fusiliers were.hard hit, this famous regiment losing a major, five captains, three lieutenants, and about two hundred men.

On October 20th, the situation being still obscure, the Twentieth Brigade carried out a reconnaissance towards Menin. The 2nd Wilts and 2nd Scots Fusiliers, of the Twenty-first Brigade, covered their left flank. The enemy, however, made a vigorous attack upon the Twenty-second Brigade to the north, especially upon the Welsh Fusiliers, so the reconnaissance had to fall back again, the 1st Grenadier Guards sustaining some losses. The two covering regiments were also hard pressed, especially the Wiltshires, who were again attacked during the night, but repulsed their assailants.

A Deadly Ordeal

From this time onwards the Seventh. Division was to feel ever more and more the increasing pressure as the German army corps from day to day brought their weight to bear upon a thin extended line of positions held by a single division. It will be shown that they were speedily reinforced by the First Corps, but even after its advent the Germans were still able to greatly outnumber the British force. The story from this time onwards is one of incessant and desperate attacks by day and often by night. At first the division was holding the position alone, with the help of their attendant cavalry, and their instructions were to hold on to the last man until help could reach them. In the case of some units these instructions were literally fulfilled. One great advantage lay with the British. They were first-class trained soldiers, the flower of the Army, while their opponents, however numerous, were of the newly-raised reserve corps, which showed no lack of bravery, but contained a large proportion of youths and elderly men in the ranks. Letters from the combatants have described the surprise and even pity which filled the minds of the British when they saw the stormers hesitate upon the edge of the trenches which they had so bravely approached, and stare down into them uncertain what they should do. But though the ascendancy of the British infantry was so great that they could afford to disregard the inequality of numbers, it was very different with the artillery. The German gunners were as good as ever, and their guns as powerful as they were numerous. The British had no howitzer batteries at all with this division, while the Germans had many. It was the batteries which caused the terrific losses. It may be that the Seventh Division, having had no previous experience in the campaign, had sited their trenches with less cunning than would have been shown by troops who had already faced the problem of how best to avoid high explosives. Either by sight or by aeroplane report the Germans got the absolute range of some portions of the British position, pitching their heavy shells exactly into the trenches, and either blowing the inmates to pieces or else burying them alive, so that in a little time the straight line of the trench was entirely lost, and became a series of ragged pits and mounds. The head-cover for shrapnel was useless before such missiles, and there was nothing for it but either to evacuate the line or to hang on and suffer. The Seventh Division hung on and suffered, but no soldiers can ever have been exposed to a more deadly ordeal. When they were at last relieved by the arrival of reinforcements and the consequent contraction of the line, they were at the last pitch of exhaustion, indomitable in spirit, but so reduced by their losses and by the terrific nervous strain that they could hardly have held out much longer.

A short account has been given of what occurred to the division up to October 20th. It will now be carried on for a few days, after which the narrative must turn to the First Corps, and show why and how they came into action to the north of the hard-pressed division. It is impossible to tell the two stories simultaneously, and so it may now be merely mentioned that from October 21st Haig's Corps was on the left, and that those operations which will shortly be described covered the left wing of the division, and took over a portion of that huge German attack which would undoubtedly have overwhelmed the smaller unit had it not been for this addition of strength. It is necessary to get a true view of the operations, for it is safe to say that they are destined for immortality, and will be recounted so long as British history is handed down from one generation to another.

- ↑ Major Vandeleur was the officer who afterwards escaped from Crefeld and brought back with him a shocking account of the German treatment of our prisoners. Though a wounded man, the Major was kicked by the direct command of one German officer, and his overcoat was taken from him in bitter weather by another.