A Day at Borstal

A Day at Borstal is an article written by Arthur Conan Doyle first published in The Daily Telegraph on 27 december 1921.

Conan Doyle reported positively about the Borstal (a youth detention centre) near Rochester.

Manuscript

-

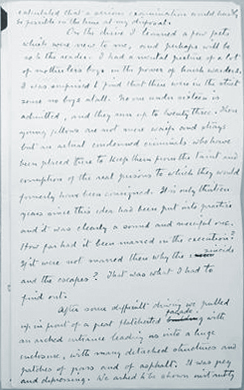

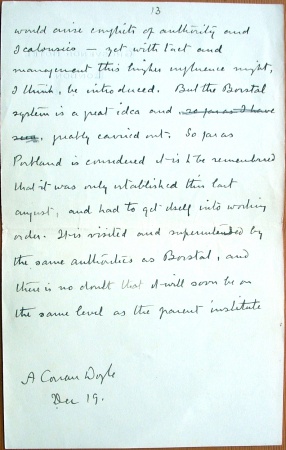

p. 1

-

p. 3

-

p. 13

Editions

- in The Daily Telegraph (27 december 1921 [UK])

- in The Straits Times (2 february 1922 [SG])

A Day at Borstal (in The Straits Times)

(2 february 1922, p. 10)

Sir A. Conan Doyle on "A Great System."

When I had a note from Mr. Shortt asking me if I would care to pay a surprise visit to one of the Borstal institutions, I felt a little grim, writes Sir A. Conan Doyle in the Daily Telegraph. Was there not a suicide scandal ? Had there not been escapes ? Certainly I would go, and certainly I would report, but only on my own conditions. It should be really a surprise visit. I should be allowed to go where I would. I should be left alone with the lads. I should be party to no white-washing, and should give an absolutely honest report. Every request was cheerfully met, so I chose my own day, had Mr. Shortt's promise that no one should know it, and, finally, in his company and that of Colonel Fleming, drove down to the parent institution, which takes its name from a village near Rochester. The Portland establishment is only a recent branch, and is so far distant that I calculated that a serious examination would hardly be possible in the time at my disposal.

On the drive I learned a few facts which were new to me, and perhaps will be so to the reader. I had a mental picture of a lot of motherless boys in the power of harsh warders. I was surprised to find that there were, in the strict sense, no boys at all. No one under 16 is admitted, and they run up to 23. These young fellows are not mere waifs and strays, but are actually condemned criminals who have been placed there to keep them from the taint and corruption of the real prisons to which they would formerly have been consigned. It is only thirteen years since this idea had been put into practice, and it was clearly a sound and merciful one. How far had it been marred in the execution ? If it were not marred, then why the suicide and the escapes ? That war what I had to find out.

After some difficult driving we pulled up in front of a great, flat-chested facade, with an arched entrance, leading us into a huge enclosure, with many detached structures and patches of grass and of asphalt it was grey and depressing. We asked to be shown instantly to the Governor, preparatory to ransacking his eatablishment. We should hurry on before there was time to put things in order. But my mind was eased when I saw Colonel Rich The Americans, when they talk of a man who is specially fit for his job, call him a "hand-picked man." Colonel Rich was clearly a hand-picked man. Tall and handsome with a pleasant voice and wise, kind eyes, he looked the ideal man for the place. There was more of the University in his appearence and bearing than of the Army. At first glance he reminded me of Alfred Lyttelton, and no type could be better than that. I would have trusted my son to that man's guardianship. A great black dog fawned at his knee, and before him stood a lad whose time was completed, and who was receiving a few kindly words of advice before going out into the world.

"Nobody is Ever Flogged."

What would we like to see first ? I was clear that the punishment cells was the place to make for, so off we went. There was nothing dramatic to chronicle. Four dreary-looking youths were working at chaff-cutting and bone-breaking, the latter for manure. These were the only penal cases out of more than 300 inmates. "What did he do ?" I asked, as I gazed at one rather vacuous lad. The Governor drew me aside. "He called the wander a bloody fool. Perhaps he was, but he shouldn't have said so." The next had lost his temper and kicked a plate over the staircase. The third had escaped and been brought back. I took him aside and asked him why he had escaped. He grinned sheepishly. On my pressing him he told me that his time was up on the first of the month, but he was not released; so on the 20th he took French leave. This seemed not unreasonable, but on inquiry it proved that the story was only a half truth, for his time had still two years to run. He was to be released as an act grace upon the first, but was detained while they secured a bi-let for him to go to. The foolish fellow by his impatience had brought himself back into the cells.

"How many floggings have you ?" I asked Colonel Rich. He looked at me in surprise. "Nobody is ever flogged," he said. "It would be easier sometimes if one could do so." It seems that before corporal punishment could be inflicted, not only the consent of the Visiting Committee but also of the Home Secretary had to be obtained. I can't remember that in my school days the British Constitution ever interfered between me and the rod. Young aristocrats are beaten in England, but never young criminals. It seems a strange inversion.

But what were the punishments ? Diet, I suggested. No, the same nutrition must be given every day. Was there, then, no punishment, save these penal cells with their special tasks ? Yes, if a lad was very troublesome his jam might be stopped at tea. By this time my visions of pale-faced victims and brutal warders were beginning to fade.

But what about the suicide ? In the various Borstal institutes there are some 1.500 people, many of them on the borderland which separates crime from mental weakness. Common-sense suggested that with all the supervision in the world it would be impossible to guard against any possible scandal. But had there not been a number of threatened suicides ? One of the lads was actually there and described the situation to Colonel Fleming with some humour. The young rascals had discovered this method of taking a rise out of the warders. "Nothing," said he, "puts the wind up an officer like saying you'll do yourself in." He chuckled much over the idea. His comrade at Portland may have really meant business, but it is a fact that he only kicked over the stool when he heard the warder's key in the door, and that he would have been easily cut down had the man not been detained in the pasaage. It may have been bona-fide or it may not, but certainly the others were an ingenious conspiracy to annoy. Remember that you are not dealing with a board school but with some of the most clever and unscrupulous young rascals in the country.

The Lure of Adventure.

But there are the escapes. I said to one lad, "Well, you haven't escaped yet ?" "No," he said, "nor don't intend to neither." But some of them do, and how to prevent it is an insoluble problem, for the whole idea of the place is to give the boys comparative liberty and if they choose to use it by making off into the woods, one could only stop it by changing the system into one of confinement. Surely it is better to let a few run than to turn the place into an ordinary gaol. But don't call it a scandal. It is not the hardship of the institution, but it is the lure of a adventure which leads thein away. We must be content to accept it as the inevitable result of putting trust in a number of lads, some of whom will abuse your confidence.

Borstal runs eleven football teams, and its first eleven is well up in the local league A boxing competition was going on. A concert on lecture is given every Saturday evening. I think a cinema might well be added. It would cost little, and there is no more subtle and unobtrusive sermon than a well-chosen film.

I took aside the Roman Catholic priest Father Nugent, an independent man, and asked him if he could suggest any improvement. He told me some of his experiences but had little to suggest as to amendments. He seemed uncertain whether the one-be-cell or the long dormitory was the better. I inspected both cells and beds, and found them very neat and comfortable. Poor chaps, it was sad to see the little group of home photographs which many of them had collected. Once a month on an average a visitor or a letter was permitted.

Their dinner was ready, and I asked to be allowed to share it, so all three of us ended be having a plate of the really excellent soup which with boiled potato, and great hunks of bread, formed their midday meal. I went over their weekly dietary, and thought that, with their outdoor life, a larger proportion of fresh food might be allowed. The Home Secretary agreed, and promised that it would be attended to. As to the quantity the lads eat, it appalled me to see their plates, with the pyramids upon them.

There were numerous training schools each full of young craftsmen, the smiths, the tailors, the shoemakers, the carpenters and the bricklayers — the latter ended in building an outhouse. One lad told us proudly that he could lay 300 bricks in five hours. Another who had been liberated had earned £5 a week ever since at this trade. I took several boys aside and had private talks with them. "I am very happy here, sir." "I would not be any where else." It is easy enough to tell if boy is lying. His eyes contradict his tongue. These boys were absolutely honest.

So it came about that. I drove back to London feeling very much happier on the subject than I had been. It is a splendid scheme, and it works splendidly.