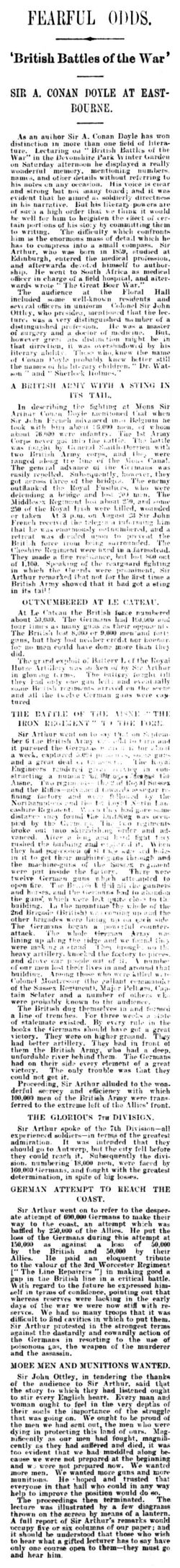

Fearful Odds: British Battles of the War

Fearful Odds: British Battles of the War is an article published in The Eastbourne Gazette on 19 may 1915.

Report of the lecture by Arthur Conan Doyle on 15 may 1915 in Eastbourne, titled "British Battles of the War".

Report

FEARFUL ODDS.

'British Battles of the War'

SIR A. CONAN DOYLE AT EASTBOURNE.

As an author Sir A. Conan Doyle has won distinction in more than one field of literature. Lecturing on "British Battles of the War" in the Devonshire Park Winter Garden on Saturday afternoon he displayed a really wonderful memory, mentioning numbers, names, and other details without referring to his notes on any occasion. His voice is clear and strong but not many toned; and it was evident that he aimed as soldierly directness in his narrative. But his literary powers are of such a high order that we think it would be well for him to heighten the effect of certain portions of his story by committing them to writing. The difficulty which confronts him is the enormous mass of detail which he has to compress into a small compass. Sir Arthur, who was born in 1859, studied at Edinburgh, entered the medical profession, and afterwards devoted himself to authorship. He went to South Africa as medical officer in charge of a field hospital, and afterwards wrote "The Great Boer War."

The audience at the Floral Hall included some well-known residents and several officers in uniform Colonel Sir John Ottley, who presided, mentioned that the lecturer was a very distinguished member of a distinguished profession. He was a master of surgery and a doctor of medicine. But, however great ais distinction might be in that direction, it was overshadowed by his literary ability. These who knew the name of Conan Doyle probably knew better still the names of his literary children, "Dr. Watson" and "Sherlock Holmes."

A BRITISH ARMY WITH A STING IN ITS TAIL.

In describing the fighting at Mons Sir Arthur Conan Doyle mentioned that when Sir John French advanced into Belgium he took with him about 86,000 men, of whom about 76,000 were infantry. The 1st Army Corps never got into the battle. The battle was fought by General Smith-Dorrien with two British Army corps, and they were ranged along the line of the Mons canal. The general advance of the Germans was easily repelled. Subsequently, however, they got across three of the bridges. The enemy outflanked the Royal Fusiliers, who were defending a bridge and lost 200 men. The Middlesex Regiment lost about 250, and some 250 of the Royal Irish were killed, wounded or taken. At 3 p.m. on August 23 Sir John French received the telegram informing him that he was enormously outnumbered, and a retreat was decided upon to prevent the British force from being surrounded. The Cheshire Regiment were fixed in a farmstead. They made a fine resistance, but lost 800 out of 1,100. Speaking of the rearguard fighting in which the Guards were prominent, Sir Arthur remarked that not for the first time a British Army showed that it had got a sting in its tail.

OUTNUMBERED AT LE CATEAU.

At Le Cateau the British force numbered about 50,000. The Germans had 180,000 and four times as many guns as their opponents. The British lost 8,000 or 9,000 men and forty guns, but they lost neither credit nor honour, for no men could have done more than they did.

The grand exploit of Battery L of the Royal Horse Artillery was spoken of by Sir Arthur in glowing terms. The battery fought till they had only one gun left; and eventually some British regiments arrived on the scene and all the twelve German guns were captured.

THE BATTLE OF THE AISNE. "THE IRON REGIMENT" TO THE FORE.

Sir Arthur went on to say that on September 6 the British Army was ... to turn and it pursued the Germans ... for about a week, captured 3,000 prisoners, some guns and a great deal of transport. The Royal Engineers rendered ... in constructing a number ... the Aisne. Two regiments of the 2nd Royal Sussex and the Rifles — advanced towards to sugar refining factory and were followed by the Northamptons and the ... Royal North Lancashire Regiment. When they had gone distance they found the ... was occupied by the Germans. The two regiments broke out into skirmishing order and advanced. After a long and hard fight they rushed the ... it. When they had possession of it they ... in it to get thei machine guns through and the machine-guns of the Sussex regiment were put inside teh factory. There were twelve German guns which attempted to open fire. The British ... the gunners and horses, and the Germans had to abandon the guns, which were left quite close to the building. In the meantime the whole of the 2nd Brigade (British) was coming up and the other brigades were lining up on each side. The Germans began a powerful counter-attack. The whole German Army was lining up along the ridge and we found they were making a stand. They brought on the heavy artillery, knocked the factory to pieces, and drove car people out of it. A number of our men lost their lives in and around that building. Among those who were killed were Colonel Montressor (the gallant commander of the Sussex Regiment), Major Pellam, Captain Sclater and a number of others who were probably known to the audience.

The British dug themselves in and formed a line of trenches. For three weeks a state of stalemate existed. By every rule in the books the Germans should have got a great victory. They were on higher ground. They had better artillery. They had in front of them the British Army, who had a deep, unfordable river behind them. The Germans had on their side every element of a great victory. The only trouWe was that they could not get it.

Proceeding, Sir Arthur alluded to the wonderful secrecy and efficiency with which 100,000 men of the British Army were transferred to the extreme left of the allies' front.

THE GLORIOUS 7TH DIVISION.

Sir Arthur spoke of the 7th Division — all experienced soldiers — in terms of the greatest admiration. It was intended thirst they should go to Antwerp, but the city fell before they could reach it. Subsequently the division, numbering 18,000 men, were faced by 160,000 Germans, and fought with the greatest determination, in spite of big losses.

GERMAN ATTEMPT TO REACH THE COAST.

Sir Arthur went on to refer to the desperate attempt of 600,000 Germans to make their way to the coast, an attempt which was baffled by 250,000 of the Allies. He put the loss of the Germans during this attempt at 150,000 as against a loss of 50,000 by the British and 50,000 by their Allies. He paid an eloquent tribute to the valour of the 3rd Worcester Regiment ["The Line Repairers"] in making good a gap in the British line in a critical battle. With regard to the future he expressed himself in terms of confidence, pointing out that whereas reserves were lacking in the early days of the war we were now stiff with reserves. We had so many troops that it was difficult to find cavities in which to put them. Sir Arthur protested in the strongest terms against the dastardly and cowardly action of the Germans in resorting to the use of poisonous gas, the weapon of the murderer and the assassin.

MORE MEN AND MUNITIONS WANTED.

Sir John Ottley, in tendering the thanks of the audience to Sir Arthur, said that the story to which they had listened ought to stir every English heart. Every man and woman ought to feel in the very depths of their souls the importance of the struggle that was going on. We ought to be proud of the men we had sent out, the men who were dying in protecting this land of ours. Magnificently as our men had fought, magnificently as they had suffered and died, it was too evident that we had muddled along because we were not prepared at the beginning and we were not prepared now. We wanted more men. We wanted more guns and more munitions. He hoped and trusted that everyone in that hall who could in any way help to improve the position would do so.

The proceedings then terminated. The lecture was illustrated by a few diagrams thrown on the screen by means of a lantern. A full report of Sir Arthur's remarks would occupy five or six columns of our paper ; and it should be understood that those who wish to hear what a gifted lecturer has to say have only one course open to them— they must go and hear him.