Lady Hilda's Mystery

| << No. 2 : The Duke's Feather | The Adventures of Picklock Holes | No. 4 : The Escape of the Bull-Dog >> |

Lady Hilda's Mystery is the 3rd story of the first series of Sherlock Holmes parodies: The Adventures of Picklock Holes written by R. C. Lehmann (aka Cunnin Toil) starring Picklock Holes as the detective and Potson as his sidekick. First published on 26 august 1893 in Punch magazine. Illustration by E. J. Wheeler.

Lady Hilda's Mystery

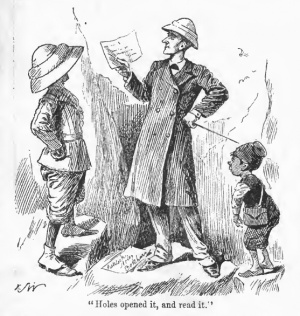

Illustration by E. J. Wheeler

A day or two after the stirring events which I have related as taking place at Blobley-in-the-Marsh, and of which, it will be remembered, I was myself an astonished spectator, I happened to be travelling, partly for business, partly for pleasure, through one of the most precipitous of the inaccessible mountain-ranges of Bokhara. It is unnecessary for me to state in detail the reasons that had induced me once more to go so far a-field. One of the primary elements in a physician's success in his career is, that he should be able to guard, under a veil of impenetrable silence, the secrets confided to his care. It cannot, therefore, be expected of me that I should reveal why his Eminence the Cardinal Dacapo, one of the most illustrious of the Princes of the Church, desired that I should set off to Bokhara. When the memoirs of the present time come to be published, it is possible that no chapter of them will give rise to bitterer discussion than that which narrates the interview of the redoubtable Cardinal with the humble author of this story. Enough, however, of this, at present. On some future occasion much more will have to be said about it. I cannot endure to be for ever the scape-goat of the great, and, if the Cardinal persists in his refusal to do me justice, I shall have, in the last resort, to tell the whole truth about one of the strangest affairs that ever furnished gossip for all the most brilliant and aristocratic tea-tables of the Metropolis.

I was walking along the narrow mountain path that leads from Balkh to Samarcand. In my right hand I held my trusty kirghiz, which I had sharpened only that very morning. My head was shaded from the blazing sun by a broad native mollah, presented to me by the Khan of Bokhara, with whom I had spent the previous day in his Highness's magnificent marble and alabaster palace. As I walked I could not but be sensible of a curiously strained and tense feeling in the air — the sort of atmosphere that seems to be, to me at least, the invariable concomitant of country-house guessing-games. I was at a loss to account for this most curious phenomenon, when, looking up suddenly, I saw on the top of an elevated crag in front of me the solitary and impassive figure of Picklock Holes, who was at that moment engaged on one of his most brilliant feats of induction. He evinced no surprise whatever at seeing me. A cold smile lingered for a moment on his firm and secretive lips, and he laid the tips of his fingers together in his favourite attitude of deep consideration.

"How are you, my dear Potson?" he began. "What? not well? Dear me, dear me, what can it mean? And yet I don't think it can have been the fifth glass of sherbet which you took with the fourteenth wife of the Khan. No, I don't think it can have been that."

"Holes, you extraordinary creature," I broke in; "what on earth made you think that I drank five glasses of sherbet with the Khan's fourteenth wife?"

"Nothing simpler, my dear fellow. Just before I saw you a native Bokharan goose ran past this rock, making, as it passed, a strange hissing noise, exactly like the noise made by sherbet when immersed in water. Five minutes elapsed, and then you appeared. I watched you carefully. Your lips moved, as lips move only when they pronounce the word fourteen. You then smiled and scratched your face, from which I immediately concluded you were thinking of a wife or wives. Do you follow me?"

"Yes, I do, perfectly," I answered, overjoyed to be able to say so without deviating from the truth; for in following his reasoning I did not admit its accuracy. As to that I said nothing, for I had drunk sherbert with no one, and consequently had not taken five glasses with the fourteenth wife of the Khan. Still, it was a glorious piece of guess-work on the part of my matchless friend, and I expressed my admiration for his powers in no measured terms.

"Perhaps," said Holes, after a pause, "you are wondering why I am here. I will tell you. You know Lady Hilda Cardamums?"

"What, the third and loveliest daughter of the Marquis of Sassafras?"

"The same. Two days ago she left her boudoir at Sassafras Court, saying that she would return in a quarter of an hour. A quarter of an hour elapsed, the Lady Hilda was still absent. The whole household was plunged in grief, and every kind of surmise was indulged in to account for the lovely girl's disappearance. Under these circumstances the Marquis sent for me, and that," said Holes, "is why I am here."

"But," I ventured to remark, "do you really expect to find Lady Hilda here in Bokhara, on these inhospitable precipices, where even the wandering Bactrian finds his footing insecure? Surely it cannot be that you have tracked the Lady Hilda hither?"

"Tush," said Holes, smiling in spite of himself at my vehemence. "Why should she not be here? Listen. She was not at Sassafras Court. Therefore, she must have been outside Sassafras Court. Now in Bokhara is outside Sassafras Court, or, to put it algebraically, in Bokhara = outside Sassafras Court.

"Substitute 'in Bokhara' for 'outside Sassafras Court,' and you get this result—"

"She must have been in Bokhara."

"Do you see any flaw in my reasoning?"

For a moment I was unable to answer. The boldness and originality of this master-mind had as usual taken my breath away. Holes observed my emotion with sympathy.

"Come, come, my dear fellow!" he said; "try not to be too much overcome. Of course, I know it is not everybody who could track the mazes of a mystery so promptly; but, after all, by this time you of all people in the world ought to have grown accustomed to my ways. However, we must not linger here any longer. It is time for us to restore Lady Hilda to her parents."

As Holes uttered these words a remarkable thing happened. Round the corner of the crag on which we were standing came a little native Bokharan telegraph boy. He approached Holes, salaamed deferentially, and handed him a telegram. Holes opened it, and read it without moving a muscle, and then handed it to me. This is what I read:—

"To Holes, Bokhara.

"Hilda returned five minutes after you left. Her watch had stopped. Deeply grateful to you for all your trouble. Sassafras."

There was a moment's silence, broken by Holes.

"No," he said, "we must not blame the Lady Hilda for being at Sassafras Court and not in Bokhara. After all, she is young and necessarily thoughtless."

"Still, Holes," I retorted, with some natural indignation, "I cannot understand how, after your convincing induction, a girl of any delicacy of feeling can have remained away from Bokhara."

"I knew she would do so," said my friend, calmly.

"Holes, you are more wonderful than ever," was all that I could murmur. So that is the true story of Lady Hilda Cardamums' return to her family.