Three of Them I. A Chat About Children, Snakes and Zebus

A Chat About Children, Snakes and Zebus is the first episode of the series Three of Them written by Arthur Conan Doyle first published in The Strand Magazine on april 1918.

Editions

- in The Strand Magazine (april 1918 [UK]) 3 photos and 2 illustrations by L. Hocknell

- in Everybody's Magazine (september 1918 [US]) 6 ill. by Gordon Ross

- in Three of Them (1918, George H. Doran Co. [US])

- in Danger! and Other Stories (1918-1929)

- in Three of Them (2 november 1923, John Murray [UK]) 3 photos on dustjacket

Illustrations

- Illustrations by L. Hocknell and photos in The Strand Magazine (april 1918)

-

Three of Them. I. A Chat about Children, Snakes, and Zebus.

-

"He has been found holding a buttercup under the mouth of a slug 'to see if he likes butter.'"

-

Baby.

-

Laddie.

-

Dimples.

- Illustrations by Gordon Ross in Everybody's Magazine (september 1918)

-

Laddie.

-

Baby.

-

Dimples.

-

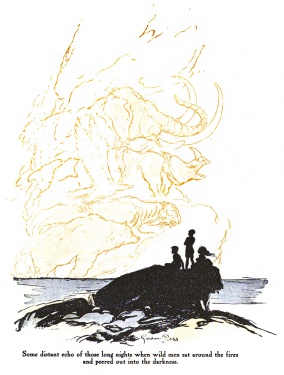

Some distant echo of those long nights when wild men sat around the fires and peered out into the darkness.

-

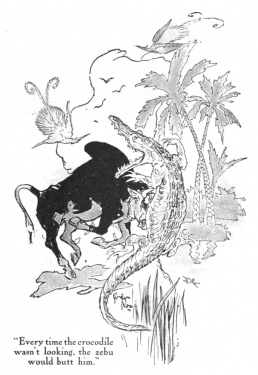

"Every time the crocodile wasn't looking, the zebu would butt him."

-

"A strictor couldn't swallow a porkpine, could he?"

Three of Them: I. A Chat About Children, Snakes, and Zebus

These little sketches are called "Three of Them," but there are really five, on and off the stage. There is Daddy, a lumpish person with some gift for playing Indian games when he is in the mood. He is then known as "The Great Chief of the Leatherskin Tribe." Then there is my Lady Sunshine. These are the grown-ups, and don't really count. There remain the three, who need some differentiating upon paper, though their little spirits are as different in reality as spirits could be all beautiful and all quite different. The eldest is a boy of eight whom we shall call "Laddie." If ever there was a little cavalier sent down ready-made it is he. His soul is the most gallant, unselfish, innocent thing that ever God sent out to get an extra polish upon earth. It dwells in a tall, slight, well-formed body, graceful and agile, with a head and face as clean-cut as if an old Greek cameo had come to life, and a pair of innocent and yet wise grey eyes that read and win the heart. He is shy and does not shine before strangers. I have said that he is unselfish and brave. When there is the usual wrangle about going to bed, up he gets in his sedate way. "I will go first," says he, and off he goes, the eldest, that the others may have the few extra minutes while he is in his bath. As to his courage, he is absolutely lion-hearted where he can help or defend any one else. On one occasion Daddy lost his temper with Dimples (Boy Number 2), and, not without very good provocation, gave him a tap on the side of the head. Next instant he felt a butt down somewhere in the region of his waist-belt, and there was an angry little red face looking up at him, which turned suddenly to a brown mop of hair as the butt was repeated. No one, not even Daddy, should hit his little brother. Such was Laddie, the gentle and the fearless.

Then there is Dimples. Dimples is nearly seven, and you never saw a rounder, softer, dimplier face, with two great roguish, mischievous eyes of wood-pigeon grey, which are sparkling with fun for the most part, though they can look sad and solemn enough at times. Dimples has the making of a big man in him. He has depth and reserve in his tiny soul. But on the surface he is a boy of boys, always in innocent mischief. "I will now do mischief," he occasionally announces, and is usually as good as his word. He has a love and understanding of all living creatures, the uglier and more slimy the better, treating them all in a tender, fairy-like fashion which seems to come from some inner knowledge. He has been found holding a buttercup under the mouth of a slug "to see if he likes butter." He finds creatures in an astonishing way. Put him in the fairest garden lawn, and presently he will approach you with a newt, a toad, or a huge snail in his custody. Nothing would ever induce him to hurt them, but he gives them what he imagines to be a little treat and then restores them to their homes. He has been known to speak bitterly to the Lady when she has given orders that caterpillars be killed if found upon the cabbages, and even the explanation that the caterpillars were doing the work of what he calls "the Jarmans" did not reconcile him to their fate.

He has an advantage over Laddie, in that he suffers from no trace of shyness and is perfectly friendly in an instant with any one of every class of life, plunging straight into conversation with some such remark as "Can your Daddy give a war-whoop?" or "Were you ever chased by a bear?" He is a sunny creature but combative sometimes, when he draws down his brows, sets his eyes, his chubby cheeks flush, and his lips go back from his almond-white teeth. "I am Swankie the Berserker," says he, quoting out of his favourite "Erling the Bold," which Daddy reads aloud at bed-time. When he is in this fighting mood he can even drive back Laddie, chiefly because the elder is far too chivalrous to hurt him. If you want to see what Laddie can really do, put the small gloves on him and let him go for Daddy. Some of those hurricane rallies of his would stop Daddy grinning if they could get home, and he has to fall back off his stool in order to get away from them.

If that latent power of Dimples should ever come out, how will it be manifest? Surely in his imagination. Tell him a story and the boy is lost. He sits with his little round, rosy face immovable and fixed, while his eyes never budge from those of the speaker. He sucks in everything that is weird or adventurous or wild. Laddie is a rather restless soul, eager to be up and doing; but Dimples is absorbed in the present if there be something worth hearing to be heard. In height he is half a head shorter than his brother, but rather more sturdy in build. The power of his voice is one of his noticeable characteristics. If Dimples is coming you know it well in advance. With that physical gift upon the top of his audacity, and his loquacity, he fairly takes command of any place in which he may find himself, while Laddie, his soul too noble for jealousy, becomes one of the laughing and admiring audience.

Then there is Baby, a dainty elfin Dresden-china little creature of five, as fair as an angel and as deep as a well. The boys are but shallow, sparkling pools compared with this little girl with her self-repression and dainty aloofness. You know the boys, you never feel that you quite know the girl. Something very strong and forceful seems to be at the back of that wee body. Her will is tremendous. Nothing can break or even bend it. Only kind guidance and friendly reasoning can mould it. The boys are helpless if she has really made up her mind. But this is only when she asserts herself, and those are rare occasions. As a rule she sits quiet, aloof, affable, keenly alive to all that passes and yet taking no part in it save for some subtle smile or glance. And then suddenly the wonderful grey-blue eyes under the long black lashes will gleam like coy diamonds, and such a hearty little chuckle will come from her that every one else is bound to laugh out of sympathy. She and Dimples are great allies and yet have continual lovers' quarrels. One night she would not even include his name in her prayers, "God bless" every one else, but not a word of Dimples. "Come, come, you must!" urged the Lady. "Well, then, God bless horrid Dimples!" said she at last, after she had named the cat, the goat, her dolls, and her Wriggly.

That is a strange trait, the love for the Wriggly. It would repay thought from some scientific brain. It is an old, faded, disused downy from her cot. Yet go where she will, she must take Wriggly with her. All her toys put together would not console her for the absence of Wriggly. If the family go to the seaside, Wriggly must come too. She will not sleep without the absurd bundle in her arms. If she goes to a party she insists upon dragging its disreputable folds along with her, one end always projecting "to give it fresh air." Every phase of childhood represents to the philosopher something in the history of the race. From the newborn baby which can hang easily by one hand from a broomstick with its legs drawn up under it, the whole evolution of mankind is re-enacted. You can trace clearly the cave-dweller, the hunter, the scout. What, then, does Wriggly represent? Fetish worship nothing else. The savage chooses some most unlikely thing and adores it. This dear little savage adores her Wriggly.

So now we have our three little figures drawn as clearly as a clumsy pen can follow such subtle elusive creatures of mood and fancy. We will suppose now that it is a summer evening, that Daddy is seated smoking in his chair, that the Lady is listening somewhere near, and that the three are in a tumbled heap upon the bearskin before the empty fireplace trying to puzzle out the little problems of their tiny lives. When three children play with a new thought it is like three kittens with a ball, one giving it a pat and another a pat, as they chase it from point to point. Daddy would interfere as little as possible, save when he was called upon to explain or to deny. It was usually wiser for him to pretend to be doing something else. Then their talk was the more natural. On this occasion, however, he was directly appealed to.

"Daddy!" asked Dimples.

"Yes, boy."

"Do you fink that the roses know us?"

Dimples, in spite of his impish naughtiness, had a way of looking such a perfectly innocent and delightfully kissable little person that one felt he really might be a good deal nearer to the sweet secrets of Nature than his elders. However, Daddy was in a material mood.

"No, boy; how could the roses know us?"

"The big yellow rose at the corner of the gate knows me."

"How do you know that?"

"'Cause it nodded to me yesterday."

Laddie roared with laughter.

"That was just the wind, Dimples."

"No, it was not," said Dimples, with conviction. "There was none wind. Baby was there. Weren't you, Baby?"

"The wose knew us," said Baby, gravely.

"Beasts know us," said Laddie. "But then beasts run round and make noises. Roses don't make noises."

"Yes, they do. They rustle."

"Woses wustle," said Baby.

"That's not a living noise. That's an all-the-same noise. Different to Roy, who barks and makes different noises all the time. Fancy the roses all barkin' at you. Daddy, will you tell us about animals?"

That is one of the child stages which takes us back to the old tribe life their inexhaustible interest in animals, some distant echo of those long nights when wild men sat round the fires and peered out into the darkness, and whispered about all the strange and deadly creatures who fought with them for the lordship of the earth. Children love caves, and they love fires and meals out of doors, and they love animal talk all relics of the far distant past.

"What is the biggest animal in South America, Daddy?"

Daddy, wearily: "Oh, I don't know."

"I s'pose an elephant would be the biggest?"

"No, boy; there are none in South America."

"Well, then, a rhinoceros?"

"No, there are none."

"Well, what is there, Daddy?"

"Well, dear, there are jaguars. I suppose a jaguar is the biggest."

"Then it must be thirty-six feet long."

"Oh, no, boy; about eight or nine feet with his tail."

"But there are boa-constrictors in South America thirty-six feet long."

"That's different."

"Do you fink," asked Dimples, with his big, solemn, grey eyes wide open, "there was ever a boa-'strictor forty-five feet long?"

"No, dear; I never heard of one."

"Perhaps there was one, but you never heard of it. Do you fink you would have heard of a boa-'strictor forty-five feet long if there was one in South America?"

"Well, there may have been one."

"Daddy," said Laddie, carrying on the cross-examination with the intense earnestness of a child, "could a boa-contrictor swallow any small animal?"

"Yes, of course he could."

"Could he swallow a jaguar?"

"Well, I don't know about that. A jaguar is a very large animal."

"Well, then," asked Dimples, "could a jaguar swallow a boa-'strictor?"

"Silly ass," said Laddie. "If a jaguar was only nine feet long and the boa-constrictor was thirty-five feet long, then there would be a lot sticking out of the jaguar's mouth. How could he swallow that?"

"He'd bite it off," said Dimples. "And then another slice for supper and another for breakfast but, I say, Daddy, a 'stricter couldn't swallow a porkpine, could he? He would have a sore throat all the way down."

Shrieks of laughter and a welcome rest for Daddy, who turned to his paper.

"Daddy!"

He put down his paper with an air of conscious virtue and lit his pipe.

"Well, dear?"

"What's the biggest snake you ever saw?"

"Oh, bother the snakes! I am tired of them."

But the children were never tired of them. Heredity again, for the snake was the worst enemy of arboreal man.

"Daddy made soup out of a snake," said Laddie. "Tell us about that snake, Daddy."

Children like a story best the fourth or fifth time, so it is never any use to tell them that they know all about it. The story which they can check and correct is their favourite.

"Well, dear, we got a viper and we killed it. Then we wanted the skeleton to keep and we didn't know how to get it. At first we thought we would bury it, but that seemed too slow. Then I had the idea to boil all the viper's flesh off its bones, and I got an old meat-tin and we put the viper and some water into it and put it above the fire."

"You hung it on a hook, Daddy?"

"Yes, we hung it on the hook that they put the porridge pot on in Scotland. Then just as it was turning brown in came the farmer's wife, and ran up to see what we were cooking. When she saw the viper she thought we were going to eat it. 'Oh, you dirty divils!' she cried, and caught up the tin in her apron and threw it out of the window."

Fresh shrieks of laughter from the children, and Dimples repeated "You dirty divil!" until Daddy had to clump him playfully on the head.

"Tell us some more about snakes," cried Laddie. "Did you ever see a really dreadful snake?"

"One that would turn you black and dead you in five minutes?" said Dimples. It was always the most awful thing that appealed to Dimples.

"Yes, I have seen some beastly creatures. Once in the Sudan I was dozing on the sand when I opened my eyes and there was a horrid creature like a big slug with horns, short and thick, about a foot long, moving away in front of me."

"What was it, Daddy?" Six eager eyes were turned up to him.

"It was a death-adder. I expect that would dead you in five minutes, Dimples, if it got a bite at you."

"Did you kill it?"

"No; it was gone before I could get to it."

"Which is the horridest, Daddy a snake or a shark?"

"I'm not very fond of either!"

"Did you ever see a man eaten by sharks?"

"No, dear, but I was not so far off being eaten myself."

"Oo!" from all three of them.

"I did a silly thing, for I swam round the ship in water where there are many sharks. As I was drying myself on the deck I saw the high fin of a shark above the water a little way off. It had heard the splashing and come up to look for me."

"Weren't you frightened, Daddy?"

"Yes. It made me feel rather cold." There was silence while Daddy saw once more the golden sand of the African beach and the snow-white roaring surf, with the long, smooth swell of the bar.

Children don't like silences.

"Daddy," said Laddie. "Do zebus bite?"

"Zebus! Why, they are cows. No, of course not."

"But a zebu could butt with its horns."

"Oh, yes, it could butt."

"Do you think a zebu could fight a crocodile?"

"Well, I should back the crocodile."

"Why?"

"Well, dear, the crocodile has great teeth and would eat the zebu."

"But suppose the zebu came up when the crocodile was not looking and butted it."

"Well, that would be one up for the zebu. But one butt wouldn't hurt a crocodile."

"No, one wouldn't, would it? But the zebu would keep on. Crocodiles live on sand-banks, don't they? Well, then, the zebu would come and live near the sand-bank too just so far as the crocodile would never see him. Then every time the crocodile wasn't looking the zebu would butt him. Don't you think he would beat the crocodile?"

"Well, perhaps he would."

"How long do you think it would take the zebu to beat the crocodile?"

"Well, it would depend upon how often he got in his butt."

"Well, suppose he butted him once every three hours, don't you think?"

"Oh, bother the zebu!"

"That's what the crocodile would say," cried Laddie, clapping his hands.

"Well, I agree with the crocodile," said Daddy.

"And it's time all good children were in bed," said the Lady as the glimmer of the Nurse's apron was seen in the gloom.

More sources

- Everybody's Magazine (september 1918)

-

p. 42

-

p. 43

-

p. 44

-

p. 45