Three of Them V. About Naughtiness and Frogs and Historical Pictures

About Naughtiness and Frogs and Historical Pictures is the 5th episode of the series Three of Them written by Arthur Conan Doyle first published in The Strand Magazine on december 1918.

Editions

- in The Strand Magazine (december 1918 [UK]) 1 photo and 6 ill. by Tom Peddie

- in Three of Them (24 january 1919, George H. Doran Co. [US])

- in Three of Them (2 november 1923, John Murray [UK]) 3 photos

Illustrations

- Photo and illustrations by Tom Peddie in The Strand Magazine (december 1918)

-

Dramatis Personae.

-

"Charging, with clenched teeth and raging fists, at Laddie."

-

"Six large frogs were sitting head-on, with their goggle eyes turned upwards, on the grass margin of the pond."

-

"'Wriggly,' her ancient rider-down quilt fetish, was her absurd patient."

-

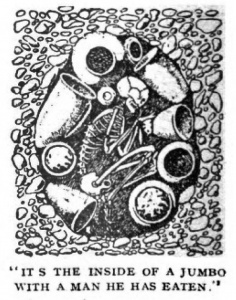

"It's the inside of a jumbo with a man he has eaten."

-

"So they guessed and prattled as they turned over those fascinating leaves."

-

"It's one man boxing against six."

Three of Them V. About Naughtiness and Frogs and Historical Pictures

There are all sorts of types and moods of childish naughtiness, as every harassed parent knows. With these three particular little people the difference was quite marked. Laddie was rarely naughty, but if he was it was in a despairing, can't-help-it, very-sorry-but-you-will-have-to-put-up-with-it way which it was difficult to deal with. Dimples, on the contrary, was cold-blooded and deliberate, with a determined "I-will-now-do-some-mischuff" air, which invited spanking. Baby was seldom obstreperous, but it took her, when it did come, in an "I-don't-care-a-blow-for-anybody-and-I'm-going-to-kick my slipper-up-the-ceiling" delirium of wickedness which it was impossible to control, so that a distressed Lady and a secretly chuckling Daddy could only wait till the weather cleared.

This is preliminary to the fact that Dimples had been exceedingly naughty in his own characteristic fashion upon the day under discussion. The truth was that he had been disappointed, and when that happened he usually ended by taking it out of some one. The disappointment was that in a too expansive moment Daddy had given him to understand that some day the tribe would gather in the dead of night and would burn down the chauffeur's cottage, with a rain of arrows directed all the while upon the windows and door. Dimples had prepared the bundles of straw, and now it had to be explained to him that Daddy had got a little beyond what was practical, and that the law had a fussy and unreasonable objection to games of that kind.

Then there was something else which had shaken his nerves up on the day before. It was a tragedy in three scenes. The first scene was that Dimples discovered a wasps' nest and stirred it up. The next was that a wasps' nest discovered Dimples and stirred him up. The third — well, the result of it was heard all over a quiet country parish, for Dimples has the largest howl to the square inch that has ever been heard. So perhaps after such an experience there was some little excuse for his being contrary after all.

But it took the queerest shape — like many of his vagaries — for his ways were original. It began by sticking remarks of his own into his prayers, which were by no means of a humble or prayerful character. Thus he said, addressing his Maker, "Please make me a good boy — which I am!" At the dictation of his mother he said, "Please teach me self-control to others," and added, "please also teach others self-control to me." Finally he showed how much he needed this self-control by completely losing his temper, and charging in tears and fury with clenched teeth and raging fists, at Laddie, who looked with gentle contempt at the furious figure, and remarked icily, "Do blow your nose!" which brought the charge to an ignominious halt. That was a touch of Laddie's knightly spirit, as cool, proud, and reserved before menace as he was soft and yielding to love.

So the rascal was punished and dismissed to the garden, where he was to remain until he felt chastened. Presently, however, his parents relented in the weak way they had, and strolled out into the garden to see the flowers, or the weather, or how the potatoes were coming on, or any excuse upon earth which would hide from each other their true purpose, which was to see how the exile was enduring his sufferings — each, of course, being perfectly aware all the time of the other's duplicity. There was no sign of the sinner, but presently, as they approached the little bush-girt pond, they heard a high, tremulous, childish voice. These were the words they heard:—

- "Once on a Cannibal Island dwelt

- A — dark — eyed — maid"

Daddy signalled caution, and the two grown-ups, as if they were playing Indian games themselves, crept up to the bushes and looked over. It was a scene which each will remember. The child stood facing the pond, swinging his hand and nodding his head as he chanted:—

"She turned very red and she snorted and said, 'I wouldn't leave my little hut for you-oo-oo! I've got one lover, and I don't want two-oo-oo.'"

His eyes as he sang this weird ballad, which he had learned from his nurse, were so fixed and set, that it was easy to discover his audience. Six large frogs were sitting head-on, with their goggle eyes turned upwards, on the grass margin of the pond. They looked absurdly like six rather overfed critics in the front row of the stalls.

"Halloa!" said Daddy, coming round the corner, and there were six flops in the water. The critics were gone.

"Halloa!" said Dimples, cheerily. He never bore a grudge, even when he had to be whipped.

"Singing to the frogs?"

And two water beetles," said Dimples, who had a curious control over animals. "There was a newt, but he wouldn't stay."

"Do you think they liked it, dear?" asked the Lady, putting her arms round her prodigal.

"Oh, yes, I know they liked it. They puff their throats in and out when they like things. I sang it right through twice."

Baby and Laddie had appeared upon the scene. Baby was swollen with pride because she had been taken the day before to London to see what she called "an octopus" about her eyes. All day she sat about in corners with a piece of glass, pretending to be "an octopus," and acting, as the true artist does, not to impress others, but for her own amusement in the demure, self-contained way which is characteristic. "Wriggly," her ancient eider-down quilt fetish, was her absurd patient, and now, up-ended in all sorts of grotesque angles, it was having its eyes examined. She had insisted upon taking it with her to London, but as it was a most disreputable rag she had to compromise that it go in a cardboard box. "Yes, dear, I enjoyed the journey, but Wriggly was so stuffy in the box !" With the extraordinary imagination of young childhood she has rigged up quite a family tree of relations for this tattered quilt, mere names most of them, but very vivid all the same. Some days before the Lady had been somewhat taken aback to learn that Baby had been married the day before. "Yes, dear, I have married Wriggly's brother," she explained, and went about for some days with an air of great importance in honour of her invisible bridegroom.

Allusion has been made in previous papers to the traces of racial stages which can be observed in the development of normal children : the animal stage, the savage stage, the hunter, the scout, even the fetish worshipper. But there is one stage which may well puzzle the student, and that is the make-pretence stage. It is well marked, comes suddenly, goes suddenly, and is very strong while it lasts. During this time the child continually pretends to be this or that, taking the pretence very seriously, carrying out the part very thoroughly, and showing wonderful ingenuity not only in its own playing of the role, but in the way in which at a moment's notice it will play up to the role of a companion, and find the right word. "I am the dog Crusoe," says Dimples. "Down, puppy, down!" says Laddie. In a moment each catches the spirit of the other. And their answers to objections come quick and sharp. "I am a thirty-foot rock snake," Laddie announced one day, and gravely acted the part till evening. "How in the world will you fit into your bed?" asked Daddy. "Oh, coil up, coil up!" said he.

Now and then the absurdity of it overcomes them and you hear that pleasantest of sounds, the sincere laughter of a child. But as a rule they are as grave as judges — if you can still use such a simile.

On one occasion early in the war Laddie, who was then a very small boy, was seen standing about with a gloomy and malevolent air of majesty. "Who are you to-day, dear?" asked his mother. "I am the German Emperor." "Oh, dear," said the Lady, "I don't think Daddy will like that at all!" "Daddy! A mere common Enghshman!" said the Emperor. That was one of Laddie's naughty days and he was getting level in this fashion. With their nimble little wits they often, consciously or not, score off their elders. "What are you going to be when you grow up?" a sympathetic visitor asked Dimples. "Oh, I'll just do nothing, the same as Daddy," was the answer.

If you want to study the strange, quick workings of the child-mind, get a book with interesting pictures which excite the imagination, and then ask the young students what they are. Daddy has an illustrated history of the ancient world which is a perpetual joy to both master and to pupils. It begins with Babylonian affairs, and then Assyrian, Egyptian, Grecian, and so on in the order of the great empires. The Three will sit in an absorbed circle upon the hearthrug looking at the wall-carvings of their ancestors and speculating as to their meaning, while Daddy, overlooking them from his arm-chair, pretends to know a good deal more than he does.

"What's this ?" he asks. The "this" happens to be a section of a neolithic grave, with skeleton and funeral pots in a circle all around it.

The children gaze at it earnestly.

"It's the inside of a Jumbo with a man he has eaten," says Dimples, with decision.

"Jumbos don't eat men," says Laddie. "Jumbos eat buns."

"Pots," says Baby. She speaks seldom, but always with decision, and is usually right.

"Yes, dear, pots. The man is dead and buried, and these are for his use in the next world. That was their idea in those days. Now, then, what is this?"

"Uncle Remus sucking a wolf."

"Romulus and Remus. They were the two children who grew up and built Rome. They were nursed by a wolf."

"I wonder if they knew Mowgli?" said Laddie. "He had a wolf for a mummy, too."

"I'm jolly glad we've got a proper mummy.' said Dimples. "Fancy saying your prayers at night to a wolf! Wouldn't it be beastly?"

"But they grew up very strong," said Daddy, "and they made such a wonderful city that in time it conquered the whole world."

"But not England," said Laddie, stoutly.

"Yes, England too."

"Oo!" cried the children.

"But not fairly," said Laddie.

"Well, it was a good thing for England," said Daddy. "We were just painted savages and they taught us some sense. Now, boys, what is this?"

It is surprising what a lot of information the eager little brains can pick up, if you make the thing a game instead of a task. They had seen some of these pictures before, and now they were off full cry, each capping the other.

"That's where the Greeks play games."

"Chariots run round that place."

"That's a temple where God lived."

"That's Babylon, and they had big stone shelves and gardens on them, and the houses were made of mud, and they are just heaps of dirt now, with dogs running about."

"That's the king's palace. That's him killing lions on the wall."

"Now," said Daddy, "what's that?"

It was certainly a puzzle. An Egyptian overseer in a wall-painting was standing with his tablets telling off the work for a line of negro slaves. The arms were all held at strange angles.

"It's one man boxing against six," said Laddie.

"It's a woman with six men that want to marry her," was Dimples' decision. Baby could only shake her little curly head.

"Soldiers," said she.

So they guessed and prattled as they turned over those fascinating leaves, now arguing about the cave-painting of a prehistoric savage, now the picture-writing of an Indian, now some strange dado taken from a Yucatan temple buried in primeval forest. Daddy leaned back and smoked and watched and listened in the gathering gloom of evening, while the firelight came and went on the eager features of the children. They were the very last buds at the end of the newest branches of the great tree of life. And here in this book they were gazing at the work of those old, old flowers upon branches which had withered so long ago. They too would work and they would pass, and there would come yet others, as far from us as we from Babylon, who would stare and guess and laugh when they saw the pictures of our little ships and aeroplanes and rude appliances for outwitting Nature. It was all working and working — and to what end? The life-urge was terrific and relentless and it pushed them always on. Monkey men crouching in a cave at one end — pure spirit, perhaps, at the other. There was more in Daddy's mind than he could tell the children as he looked at the three heads clustered over the old book before the fire.