A Worker of Wonders

The Uncharted Coast - VI. A Worker of Wonders is an article written by Arthur Conan Doyle first published in The Strand Magazine in may 1921.

Editions

- in The Strand Magazine (may 1921 [UK]) 2 illustrations by Howard Elcock, 1 photo

- in The History of Spiritualism (1926) as The Career of D. D. Home

- in The Edge of the Unknown (1930) as A Remarkable Man

Photos

-

"A deep melancholy lay upon his sensitive features as he viewed the land which contained no one whom he could call a friend."

-

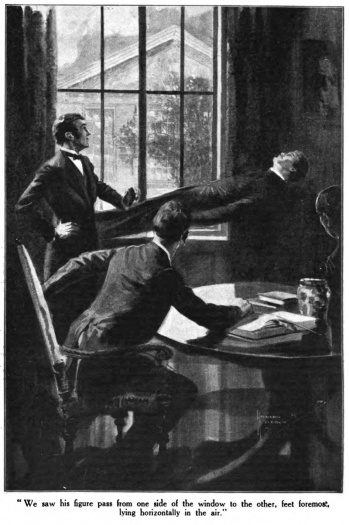

"We saw his figure pass from one side of the window to the other, feet foremost, lying horizontally in the air."

-

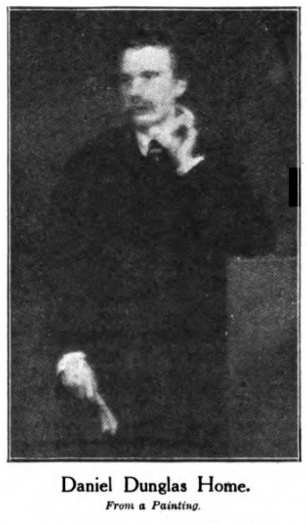

Daniel Dunglas Home.

From a painting.

The Uncharted Coast - VI. A Worker of Wonders

On the early morning of April 9th, 1855, the steam packet Africa. from Boston, was drawing into Liverpool Docks. Captain Harrison, his responsibility lifted from him, was standing on the bridge, the pilot beside him, while below the passengers had assembled, some bustling about with their smaller articles of luggage, while others lined the decks and peered curiously at the shores of Old England. Most of them showed natural exultation at the successful end of their voyage, but among them was one who seemed to have no pleasant prospects in view. Indeed, his appearance showed that his most probable destiny would make him independent of any earthly career. This was a youth some two-and-twenty years of age, tall, slim, with a marked elegance of bearing and a fastidious neatness of dress, but with a worn, hectic look upon his very expressive face, which told of the ravages of some wasting disease. Blue-eyed, and with hair of a light auburn tint, he was of the type which is peculiarly open to the attack of tubercle, and the extreme emaciation of his frame showed how little power remained with him by which he might resist it. An acute physician watching him closely would probably have given him six months of life in our humid island. Yet this young man was destined to be the instrument of God in making a greater change in English thought than any traveller for centuries — a change only now developing and destined, as I think, to revolutionize for ever our views on the most vital of all subjects. For this was Daniel Dunglas Home, a youth of Scottish birth and extraction, sprung from the noble Border family of that name, and the possessor of strange personal powers which make him, with the possible exception of Swedenborg, the most remarkable individual of whom we have any record since the age of the Apostles, whose gifts he appeared to inherit. A deep melancholy lay upon his sensitive features as he viewed the land which contained no one whom he could call friend. Tears welled from his eyes, for he was a man of swift emotions and feminine susceptibilities. Then, with a sudden resolution, he disengaged himself from the crowd, rushed down to the cabin, and fell upon his knees in prayer. He has recorded how a spring of hope and comfort bubbled up in his heart, so that no more joyous man set his foot that day upon the Mersey quay, or one more ready to meet the fate which lay before him.

But how strange a fate, and what a singular equipment with which to face this new world of strangers I He had hardly a relation in the world. His left lung was partly gone. His income was modest, though sufficient. He had no trade or profession, his education having been interrupted by his illness. In character he was shy, gentle, sentimental, artistic, affectionate, and deeply religious. He had a .strong tendency both to art and the drama, so that his powers of sculpture were considerable, and as a reciter he proved in later life that he had few living equals. But on the top of all this, and of an unflinching honesty which was so uncompromising that he often offended his own allies, there was one gift so remarkable that it threw everything else into insignificance. This lay in, certain powers, quite independent of his own volition, coming and going with disconcerting suddenness, but proving to all who would examine the proof that there was something in this man's atmosphere which enabled forces outside himself and outside our ordinary apprehension to manifest themselves upon this plane of matter. In other words, he was a medium — the greatest that the modem world has ever seen.

A lesser man might have used his extraordinary powers to found some special sect of which he would have been the undisputed high priest, or to surround himself with a glamour of power and mystery. Certainly most people in his position would have been tempted to use them for the making of money. As to this latter point, let it be said at once that never in the course of the thirty years of his strange ministry did he touch one shilling as payment for his gifts. It is on sure record that as much as two thousand pounds was offered to him by the Union Circle in Paris in the year 1857 for a single séance, and that he, a poor man and an invalid, utterly refused. "I have been sent on a mission," he said ; "that mission is to demonstrate immortality. I have never taken money for it and I never will." There were certain presents from Royalty which cannot be refused without boorishness — rings, scarf pins, and the like, tokens of friendship rather than recompense, for before his premature death there were few monarchs in Europe with whom this shy youth from the Liverpool landing stage was not upon terms of affectionate intimacy. Napoleon the Third provided for his only sister ; the Emperor of Russia sponsored his marriage. What novelist would dare to invent such a career?

But there are more subtle temptations than those of wealth. Home's uncompromising honesty was the best safeguard against those. Never for a moment did he lose his humility and his sense of proportion. "I have these powers," he would say ; "I shall be happy up to the limit of my strength to demonstrate them to you if you approach me as one gentleman should approach another. I shall be glad if you can throw any further light upon them. I will lend myself to any reasonable experiment. I have no control over them — they use me but I do not use them. They desert me for months and then come back in redoubled force. I am a passive instrument — no more." Such was his unvarying attitude. He was always the easy, amiable man of the world, with nothing either of the mantle of the prophet or of the skull-cap of the magician. Like most truly great men, there was no touch of pose in his nature. An index of his fine feeling is that when confirmation was needed for his results he would never quote any names unless he was perfectly certain that the owners would not suffer in any way through being associated with an unpopular cult. Sometimes, even after they had freely given leave, he still withheld the names, lest he should unwittingly injure a friend. When he published his first series of "Incidents in My Life" the Saturday Review waxed very sarcastic over the anonymous evidence of Countess O—— Count B—— , Count de K—— , Princess de B—— , and Mrs. S—— , who were quoted a having witnessed manifestations. In his second volume Home, having assured himself of the concurrence of his friends, filled the blanks with the names of the Counter Orsini, Count de Beaumont, Count de Komar, Princess de Beaurean, and the well-known, American hostess, Mrs. Henry Senior. Royal friends he never quoted at all, and yet it is notorious that the Emperor Napoleon, the Empress Eugenie, the Czar, the Emperor William I. of Germany, and the Kings of Bavaria and Würtemberg were all equally convinced by his extraordinary power. Never once was Home convicted of any deception either in word or in deed.

In these days, when the facts of psychic phenomena are familiar to all save those who are wilfully ignorant, we can hardly realize the moral courage which was needed by Home in putting forward his powers upholding them in public. To the average educated Briton in the material Victorian era, a man who claimed to be able to produce results which upset Newton's law of gravity, and which showed invisible mind acting upon visible matter, was prima facie a scoundrel and an impostor. The view of Spiritualism pronounced by Vice-Chancellor Gifford at the conclusion of the Home-Lyon trial that of the class to which he belonged. He knew nothing of the matter, but took it for granted that anything with such claims must be false. No doubt similar things were reported in far-off lands and ancient books, but that they could occur in prosaic, steady old England, the England of bank rates and free imports, was too absurd for serious thought. It has been recorded that at this trial Lord Gifford turned to Home's counsel and said, "Do I understand you to state that your client claims that he has been levitated into the air?" The counsel assented — on which the judge turned to the jury and made such a movement as the high priest may have made in ancient days when he rent his garments as a protest against blasphemy. In 1867 there were few of the jury who were sufficiently educated to check the judge's remarks, and it is just in that particular that we have made some progress in the fifty years between. Slow work — but Christianity took more than three hundred years to come into its own.

Take this question of levitation as a test of Home's powers. It is claimed that more than a hundred times in good light, before reputable witnesses, he floated in the air. Consider the evidence. In 1857, in a château near Bordeaux, he was lifted to the ceiling of a lofty room in the presence of Mme. Ducos, widow of the Minister of Marine, and of the Count and Countess de Beaumont. In 1860 Robert Bell wrote an article, "Stranger than Fiction," in the Cornhill. "He rose from his chair," says Bell, four or five feet from the ground... We saw his figure pass from one side of the window to the other, feet foremost, lying horizontally in the air." Dr. Gully of Malvern, a well-known medical man, and Robert Chambers, the author and publisher, were the other witnesses. Is it to be supposed that these men were lying confederates, or that they could not tell if a man were floating in the air or pretending to do so? In the same year Home was raised at Mrs. Milner Gibson's house in the presence of Lord and Lady Clarence Paget — the former passing his hands underneath him to assure himself of the fact. A few months later, Mr. Wason, a Liverpool solicitor, with seven others saw the same phenomenon. "Mr. Home," he says, "crossed the table over the heads of the persons sitting around it." He added: "I reached his hand seven feet from the floor, and moved along five or six paces as he floated above me in the air." In 1861 Mrs. Parkes, of Cornwall Terrace, Regent's Park. tells how she was present with Bulwer Lytton and Mr. Hall when Home, in her own drawing-room, was raised till his hand was on the top of the door, and then floated horizontally forward. In 1866 Mr. and Mrs. Hall, Lady Dunsany, and Mrs. Senior, in Mr. Hall's house, saw Home, his face transfigured and shining, twice rise to the ceiling, leaving a cross marked in pencil upon the second occasion, so as to assure the witnesses that they were not victims of imagination. In 1868 Lord Adare, Lord Lindsay, Captain Wynne, and Mr. Smith Barry saw Home levitate upon many occasions. A very minute account has been left by the first three witnesses of the occurrence of December 16th of this year, when, at Ashley House, Home, in a state of trance, floated out of the bedroom and into the sitting-room window, passing seventy feet above the street. After his arrival in the sitting-room he went back into the bedroom with Lord Adare, and upon the latter remarking that he could not understand how Home could have flitted through the window, which was only partially raised, "he told me to stand a little distance off. He then went through the open space head first quite rapidly, his body being nearly horizontal, and apparently rigid. He came in again feet foremost." Such was the account given by Lords Adare and Lindsay. Upon its publication, Dr. Carpenter, who earned an unenviable reputation by a perverse opposition to every fact which bore upon this question, wrote exultantly to point out that there had been a third witness who had not been heard from, assuming, without the least justification, that Captain Wynne's evidence would be contradictory. He went the length of saying, "A single honest sceptic declares that Mr. Home was sitting in his chair all the time," a statement which can only be described as false. Captain Wynne at once wrote corroborating the others, and adding, " If you are not to believe the corroborative evidence of three unimpeached witnesses, there would be an end to all justice and courts of law." So many are the other instances of Home's levitations that a long article might easily be written, upon this single phase of his mediumship. Professor Crookes was again and again a witness to the phenomenon, and refers to fifty instances which had come within his knowledge. But is there any fair-minded person, who has read the little that I have recorded above, who will not say with Professor Challis, "Either the facts must be admitted or the possibility of certifying facts by human testimony must be given up"?

But now a word of explanation. "Are we then back in the age of miracles?" cries the reader. There is no miracle — nothing on this plane is supernatural. What we see now and what we have read of in ages past are but the operation of law which has not vet been studied and defined. Already we realize something of its possibilities and of its limitations, which are as exact in their way as those of any purely physical power. We must hold the balance between those who would believe nothing and those who would believe too much. Gradually the mists will clear and we will chart the shadowy coast. When the needle first sprang up at the magnet it was not an infraction of the laws of gravity. It was that there had been the local intervention of another, stronger force. Such is the case, also, when psychic powers act upon the plane of matter. Had Home's faith in this power faltered, or had his circle been unduly disturbed, he would have fallen. When Peter lost faith he sank into the waves. Across the centuries the same cause still produced the same effect. Spiritual power is ever with us if we do not avert our faces, and nothing has been vouchsafed to Judea which is withheld from England.

It is in this respect, as a confirmation of the power of the unseen, and. as a final answer to materialism as we now understand it, that Home's public career is of such supreme importance. He was an affirmative witness of the truth of those so-called "miracles," which have been the stumbling-block for so many earnest minds, and are now destined to be the strong, solid proof of the accuracy of the original narrative. Millions of doubting souls in the agony of spiritual conflict had cried out for definite proof that all was not empty space around us, that there were powers beyond our grasp, that the ego was not a mere secretion of nervous tissue, and that the dead did really carry on this personal, unbroken existence. All this was proved by this greatest of modern missionaries to anyone who could observe and reason. It is easy to poke superficial fun at rising tables and quivering walls, but they were the nearest and most natural objects which could record in material terms that power which was beyond our human ken. A mind which would be unmoved by an inspired sentence was struck into humility and into new paths of research in the presence of even the most homely of these inexplicable phenomena. It is easy to call them puerile, but they effected the purpose for which they were sent by shaking to its foundations the complaisance of those material men of science who were brought into actual contact with them. They are to be regarded not as ends in themselves, but as the elementary means by which the mind should be diverted into new channels of thought. And those channels of thought led straight to the recognition of the survival of the spirit. "You have conveyed incalculable joy and comfort to the hearts of many people," said Bishop Clark of Rhode Island. "You have made dwelling-places light that were dark before." "Mademoiselle," said Home to the lady who was to be his wife, "I have a mission entrusted to me ; it is a great and a holy one." The famous Dr. Elliotson, immortalized by Thackeray under the name of Dr. Goodenough, was one of the leaders of British materialism. He met Home, saw his powers, and was able soon to say that he had lived all his life in darkness and had thought there was nothing in existence but the material ; but he now had a firm hope which he trusted he would hold while on earth. Innumerable instances could be quoted of the spiritual value of his work, but it has never been better summed up than in a paragraph from Mrs. Webster of Florence, who saw much of his ministry. "He is the most marvellous missionary of modern times, in the greatest of all causes, and the good that he has done cannot be reckoned. Where Mr. Home passes he bestows around him the greatest of all blessings — the certainty of a future life." Now that the details of his career can be read it is to the whole wide world that he brings this most vital of all messages.

It is curious to see how his message affected those of his own generation. Reading the account of his life written by his widow — a most convincing document, since she, of all living mortals, must have known the real man — it would appear that his most utterly whole-hearted support and appreciation came from those aristocrats of France and Russia with whom he was brought into contact. The warm glow of personal admiration and even reverence in their letters is such as can hardly be matched in any biography. In England he had a close circle of ardent supporters, a few of the upper classes, with the Halls, the Howitts, Robert Chambers, Mrs. Milner Gibson, Professor Crookes, and others. But there was a sad lack of courage among those who admitted the facts in private and stood aloof in public. Lord Brougham and Bulwer Lytton were of the type of Nicodemus, the novelist being the worst offender. The "Intelligentia" on the whole came badly out of the matter, and many an honoured name suffers in the story. Faraday and Tyndall were fantastically unscientific in their methods of prejudging a question first, and offering to examine it afterwards on the condition that their pre-judgment was accepted. Sir David Brewster said some honest things, and then, in a panic, denied that he had said them, forgetting that the evidence was on actual record. Browning wrote a long poem — if such doggerel can be called poetry — to describe an exposure which had never taken place. Carpenter earned an unenviable notoriety as an unscrupulous opponent, while proclaiming some strange spiritualistic thesis of his own. The secretaries of the Royal Society refused to take a cab drive in order to see Crookes's demonstration of the physical phenomena, while they-pronounced roundly against them. Lord Gifford inveighed from the Bench against a subject the first elements of which he did not understand. As to the clergy, such an order might not have existed during the thirty years that this, the most marvellous spiritual outpouring of many centuries, was before the public. I cannot recall the name of one British clergyman who showed any intelligent interest, and when in 1872 a full account of the St. Petersburg seances began to appear in the Times, it was cut short. according to Mr. H. T. Humphreys, "on account of strong remonstrances to Mr. Delane, the editor, by certain of the higher clergy of the Church of England." Such was the contribution of our official spiritual guides. Dr. Elliotson, the Rationalist, was far more alive than they. The rather bitter comment of Mrs. Home is, "The verdict of his own generation was that of the blind and deaf upon the man who could hear and see."

Home's charity was among his more beautiful characteristics. Like all true charity, it was secret, and only comes out indirectly and by chance. One of his numerous traducers declared that he had allowed a bill for fifty pounds to be sent in to his friend, Mr. Rhymer. In self-defence it came out that it was not a bill, but a cheque most generously sent by. Home to help this friend in a crisis. Considering his constant poverty, fifty pounds probably represented a good part of his bank balance. His widow dwells with pardonable pride upon the many evidences found in his letters after his death. "Now it is an unknown artist for whose brush Home's generous efforts had found employment ; now a distressed worker writes of his sick wife's life saved by comforts that Home provided ; now a mother thanks him for a start in life for her son. How much time and thought he devoted to helping others when the circumstances of his own life would have led most men to think only of their own needs and cares." "Send me a word from the heart that has known so often how to cheer a friend!" cries one of his protégés. "Shall I ever prove worthy of all the good you have done me?" says another letter. We find him roaming the battlefields round Paris, often under fire, with his pockets full of cigars for the wounded. A German officer writes affectionately to remind him how he saved him from bleeding to death, and carried him on his own weak back out of the place of danger. Truly Mrs. Browning was a better judge of character than her spouse, and Sir Galahad a better name than Sludge.

There are few of the varied gifts which we call "mediumistic," and St. Paul "of the spirit," which Home did not possess — indeed, the characteristic of his psychic power was its unusual versatility. We speak usually of a direct voice medium, of a trance speaker, of a clairvoyant, or of a physical medium, but Home was all four. To take St. Paul's gifts in their order he had "the word of wisdom and the word of knowledge" when in his trance utterances he described the life beyond. "The gift of healing" was with him, and the account of his curing young De Cardonne of total deafness or of Mme. de Lakine of paralysis is historical. "The operation of great works" was shown in his phenomena when the very building would shake from an unknown power. "Discerning of spirits" was continually with him. There is no note, however, of prophecy or of the gift of tongues. So far as can be traced he had little experience of the powers of other mediums, and was not immune from that psychic jealousy which is a common trait of these sensitives. Mrs. Jencken, formerly Miss Kate Fox, was the only other medium with whom he was upon terms of friendship. He bitterly resented any form of deception, and carried this excellent trait rather too far by looking with eyes of suspicion upon all forms of manifestation which did not exactly correspond with his own. This opinion, expressed in an uncompromising manner in his last book, "Lights and Shadows of Spiritualism," gave natural offence to other mediums who claimed to be as honest as himself. A wider acquaintance with phenomena would have made him more charitable. Thus he protested strongly against any seance being held in the dark, but this is certainly a counsel of perfection, for experiments upon the ectoplasm, which is the physical basis of all materializations, show that it is fatally affected by light unless it is tinted red. Home had no large experience of complete materializations, such as those obtained in those days by Miss Florrie Cook or Mme. d'Esperance, or in our own time by Mme. Bisson's medium, and therefore he could dispense with complete darkness in his own ministry. Thus his opinion was unjust to others. Again, Home declared roundly that matter could not pass through matter, because his own phenomena did not take that form, and yet the evidence that matter can in certain cases be passed through matter seems to be overwhelming. Even birds of rare varieties have been brought into seance rooms under circumstances which seem to preclude fraud, and the experiments of passing wood through wood as shown before Zollner and the other Leipzig professors were quite final, as set forth in the famous physicist's account, in "Transcendental Physics," of his experiences with Slade. Thus it may count as a small flaw in Home's character that he decried and doubted the powers which he did not himself happen to possess.

Some also might count it as a failing that he carried his message rather to the readers of society and of life than to the vast toiling masses, It is probable that Home had, in fact, the weakness as well as the graces of the artistic nature, and that lie was most at ease and happiest in an atmosphere of elegance and refinement, with a personal repulsion from all. that was sordid and ill-favoured. If there were no other reason, the precarious state of his health unfitted him for any sterner mission, and he was driven by repeated haemorrhages to seek the pleasant and refined life of Italy, Switzerland, and the Riviera. But for the prosecution of his mission, as apart from personal self-sacrifice, there can be no doubt that his message carried to the laboratory of a Crookes or to the Court of a Napoleon was more useful than if it were laid before the crowd. The assent of science and of character was needed before the public could gain assurance that such things were true. If it was not fully gained the fault lies assuredly with the hide-bound men of science and thinkers of the day, and by no means with Home, who played his part of actual demonstration to perfection, leaving it to other and less gifted men to analyse and to make public that which he had shown them. He did not profess to be a man of science, but he was the raw material of science, willing and. anxious that others should learn from him all that he could convey to the world, so that science should itself testify to religion, while religion should be buttressed upon science. When Home's message has been fully learned, an unbelieving man will not stand convicted of impiety, but of ignorance.

There was something pathetic in Home's efforts to find some creed in which he could satisfy his own gregarious instinct — for he had no claims to be a strong-minded individualist — and at the same time find a niche into which he could fit his own precious packet of assured truth. His pilgrimage vindicates the assertion of some Spiritualists that a man may. belong to any creed and carry with him the. spiritual knowledge, but it also bears out those who reply that perfect harmony with that spiritual knowledge can only be found, as matters now stand, in a special Spiritualist community. Alas that it should be so! For it is too big a thing to sink into a sect, however great that sect might become. Home began in his youth as a Wesleyan, but soon left them for the more liberal atmosphere of Congregationalism. In Italy. the artistic atmosphere of the Roman Catholic Church, and possibly its record of so many phenomena akin to his own, caused him to become a convert with an intention of joining a monastic order — an intention which his common, sense caused him to abandon. The change of religion was at a period when his psychic powers had deserted him for a year, and his confessor assured him that as they were of evil origin they would certainly never be heard of again now that he was a son of the true Church. None the less, on the very day that the . year expired they came back in renewed strength. From that time Home seems to have been only nominally a Catholic, if at all, and after his second marriage — both his marriages were to Russian ladies — he was strongly drawn towards the Greek Church, and it was under their ritual that he was at last laid to rest at St. Germain in 1886. "To another discerning of spirits" (Cor. xii. 10) is the short inscription upon that grave, of which the world has not yet heard the last.

If proof were needed of the blamelessness of Home's life, it could not be better shown than by the fact that his numerous enemies, spying ever for some opening to attack, could get nothing in his whole career upon which to comment save the wholly innocent affair which is known as the Home-Lyon case. Any impartial judge, reading the depositions in this case — they are to be found verbatim in the second series of "Incidents from My Life" — would agree that it is not blame but commiseration which was owing to Home. One could desire no higher proof of the nobility of his character than his dealings with this unpleasant freakish woman, who first insisted upon settling a large sum of money upon him, and then, her whim having changed, and her expectations of an immediate introduction into high society being disappointed, stuck at nothing in order to get it back again.

Had she merely asked for it back, there is little doubt that Home's delicate feelings would have led him to return it, even though he had been put to much trouble and expense over the matter, which had entailed a change of his name to Home-Lyon, to meet the woman's desire that he should be her adopted son. Her request, however, was so framed that he could not honourably agree to it, as it would have implied an admission that he had done wrong in accepting the gift. If one consults the original letters — which few of those who comment upon the case seem to have done — you find that Home, S. C. Hall as his representative, and Mr. Wilkinson as his solicitor implored the woman to moderate the unreasonable benevolence which was to change so rapidly into even more unreasonable malevolence. She was absolutely determined that Home should have the money and be her heir. A less mercenary man never lived, and he begged her again and again to think of her relatives, to which she answered that the money was her own to do what she pleased with, and that no relatives were dependent upon it. From the time that he accepted the new situation he acted and wrote as a dutiful son, and it is not uncharitable to suppose that this entirely filial attitude may not have been that which this elderly lady had planned out in her scheming brain. At any rate, she soon tired of her fad and reclaimed her money upon the excuse — a monstrous one to anyone who will read the letters and consider the dates — that spirit messages received through Home had caused her to take the action she had done. The case was tried in the Court of Chancery, and the judge alluded to Mrs. Lyon's "innumerable misstatements on many important particulars — Misstatements upon oath so perversely untrue that they have embarrassed the Court to a great degree and quite discredited the plaintiff's testimony." In spite of this caustic comment, and in spite also of elementary justice, the verdict was against Home on the general ground that British law put the burden of disproof upon the defendant in such a case, and complete disproof is impossible when assertion is met by counter-assertion. Even Home's worst enemies were forced to admit that the fact that he had retained the money in England and had not lodged it where it would have been beyond recovery proved his honest intentions in this the most unfortunate episode of his life.

Such, within the compass of a short sketch, was the strange fate of the young man whom we saw land upon the Liverpool pier. He was at that time twenty-two. He died in his fifty-third year. In those thirty years he threw out seed with either hand. Much fell among stones ; much was lost on the wayside ; but much found a true resting-place, and has put forth a harvest the end of which no living man can see.