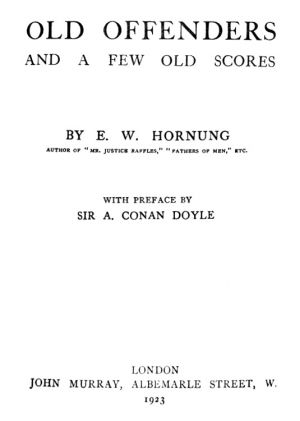

Old Offenders and a Few Old Scores

Old Offenders and a Few Old Scores is a book written by E. W. Hornung (Arthur Conan Doyle's brother-in-law) published in may 1923 by John Murray and including a preface written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The book is a collection of short stories. It was published posthumously (Hornung died in 1921 from influenza).

Preface

By the premature death of my brother-in-law, Mr. E. W. Hornung, British literature sustained a notable loss. He was but fifty-four when he passed over, and as his powers had steadily expanded with every year of his life, it is probable that they had not yet reached their full maturity. But even as it was, his output was considerable, for from the day that his "Bride from the Bush" attracted attention in the early ’nineties down to the period of the war he was always at work in his thorough conscientious way, and there was none of that work which could be called conventional, for he always brought to it a literary conscience, a fine artistic sense, and a remarkable power of vivid narrative. At his best there is no modern author who, by the sudden use of the right adjective and the right phrase, could make a scene spring more vividly to the eyes of the reader.

The Raffles stories are, of course, conspicuous examples of this, and one could not find any better example of clever plot and terse admirable narrative. But in a way they harmed Hornung, for they got between the public and his better work. Some of that work is ambitious, and fell little short of achieving the high mark at which it was aimed. "Peccavi," for example, is a very outstanding novel, deep and serious, while "Fathers of Men" is one of the very best school tales in the language, taking the masters in as well as the boys, and thereby perhaps marring the book for the latter. But it was a remarkable achievement, and might well be so, for on the one hand the whole subject of public-school education, and on the other the national game of cricket, were two of Hornung’s chief hobbies. He was the best read man in cricket lore that I have ever met, and would I am sure have excelled in the game himself if he had not been hampered by short sight and a villainous asthma. To see him stand up behind the sticks with his big pebble glasses to a fast bowler was an object lesson in pluck if not in wicket-keeping.

His sympathies were intense, and his point of view clear, and when he focussed his powers upon anything which really appealed to him the effect was remarkable. He played the part of a man during the war, and after the death of his only son he went out to serve the troops in France as best he might. His little book, "Notes of a Camp-follower," gives some of his impressions, and there are parts of it which are brilliant in their vivid portrayal. I am tempted to take a single passage lest the reader thinks I am too generous in diffuse commendation. It is the march of the Australians to mend the broken line at Amiens.

"They were marching in their own way—no strut or swing about it, but a more subtle jauntiness, a kind of mincing strut, perhaps not unconsciously sinister and unconventional, an aggressive part of themselves. But what men! What beetling chests, what muscle-swollen sleeves, what dark pugnacious clean-shaven faces! Here and there a pendulous moustache mourned the beard of some bushman of the old school, but no such adventitious aids could have improved upon the naked truculence of most of those mouths and chins. In their supercilious confidence they reminded me of the early Australian cricketers, taking the field to mow down the flower of English cricket in the days when those were our serious wars." The part which the public schools played in the war was also a great joy to Hornung. "Only our public schools could have furnished off-hand an army of natural officers, trained to lead, old in responsibility, and afraid of nothing in the world but fear itself."

It was a hard fate that when Hornung had come through it all, when he had seen peace dawn, and recovered from the first shock of his loss, with all his work lying in front of him and the prospect of quiet literary days before him, he should have met a sudden end while taking a short holiday in the South of France. It was aggravated influenza which carried him off, but he had always been delicate, and it was only his quiet courage which prevented his friends from constantly knowing it. He was loved by many, and as I dropped flowers upon his newly turned grave at St. Jean de Luz, where he lies with only a gravel path between him and George Gissing, I felt that the tribute was from many hearts besides my own.

ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE.

Old Offenders

The Saloon Passenger

As the cable was hauled in, and the usual cheering passed between tug and ship, Skrimshire unclenched his teeth and gave tongue with a gusto as cynical as it was sincere. It had just come home to him that this was the last link with land, and he beheld it broken with ineffable relief. Tuskar Rock was already a little thing astern; the Australian coast lay the width of the world away; the captain did not expect even to sight any other, and had assured Skrimshire that the average passage was not less than ninety days. So, whatever was to happen in the end, he had three months more of life, and of such liberty as a sailing-ship affords.

He descended to his cabin, locked himself in, and lay down to read what the newspapers had to say about the murder. It seemed strange to Skrimshire that this was the first opportunity he had had of reading up his own crime; but the peculiar circumstances of his departure had forbidden him many a last pleasure ashore, and he was only too glad to have the papers to read now and a state-room to himself in which to read them. There was a heavy sea running, and Skrimshire was no sailor; but he would not have been without the motion, or even its effects upon himself. Both were an incessant reminder that his cabin was not a prison cell, and could not turn into one for three months at all events. Besides, he was not the man to surrender to a malady which is largely nervous. So he lay occupied in his berth; medium-sized, dark-skinned, neither young nor middle-aged; only respectably dressed, and with salient jaw unshaven since the thing of which he read without a flicker of the heavy eyelids or a tremor of the hairy hands.

He had five papers of that morning's date; the crime was worthily reported in them all; one or two had leaders on its peculiar atrocity. Skrimshire sighed when he came to the end: it was hard that he could see no more papers for three months. The egotism of the criminal was excited within him. It was lucky he was no longer on land: he would have run any risk for the evening papers. His very anonymity as author of the tragedy—the thing to which he owed his temporary security—was a certain irritation to him. He was not ashamed of what he had done. It read wonderfully, and was already admitted to have shown that diabolical cleverness and audacity for which Skrimshire alone deserved the credit; yet it looked as though he would never get it. Thus far, at least, it was plain that there was not a shred of evidence against him, or against any person upon earth. He sighed again; smiled at himself for sighing; and, closing his eyes for the first time since the murder, slept like a baby for several hours.

Skrimshire was the only passenger in the saloon, of which he presently became the life and soul. At the first meal he yielded to the temptation of a casual allusion to the murder on the Caledonian Railway; but though they had heard of it, neither captain nor officers showed much interest in the subject, which Skrimshire dropped with a show of equal indifference. And this was his last weakness of the kind. He threw his newspapers overboard, and conquered the morbid vanity they had inspired by a superb effort of the will. Remorse he had none, and for three months certain he was absolutely safe. So he determined to enjoy himself meanwhile; and, in doing so, being a dominant personality, he managed to diffuse considerable enjoyment throughout the ship.

This man was not a gentleman in either the widest or the narrowest sense of that invidious term. He wore cheap jewellery, cheap tweeds as yellow as his boots, paper collars, and shirts of a brilliant blue. He spoke with a Cockney intonation which, in a Scottish vessel, grated more or less upon every ear. But he had funds of information and of anecdote as inexhaustible as his energy, and as entertaining as his rough good-humour. He took a lively interest in every incident of the voyage, and was as ready to go aloft in a gale of wind as to make up a rubber in any part of the ship. Within a month he was equally popular in the forecastle, the steerage, and the captain's cabin. Then one morning Skrimshire awoke with a sense that something unusual was happening, followed by an instantaneous premonition of impending peril to himself.

There were too many boots and voices over his head; the ship was bowling sedately before the north-east trades, and otherwise as still as a ship could be. Skrimshire sat up and looked through his port-hole. A liner was passing them, also outward-bound, and some three or four miles to port. There was nothing alarming in that. Yet Skrimshire went straight on deck in his pyjamas; and, on the top rung of the poop-ladder, paused an instant, his now bearded jaw more salient than it had been for weeks.

Four little flags fluttered one above the other from the peak halliards, and at the weather-rail stood the captain, a powerful figure of a man, with his long legs planted well apart, and a marine binocular glued to his eyes. Near him was the second mate, a simple young fellow, who greeted Skrimshire with a nod.

"What's up, McKendrick? What is she?"

"A Castle liner; one o' Donal' Currie's Cape boats."

"Why did you signal her?" whispered Skrimshire.

" 'Twas she signalled us."

"Do you know what it's all about?"

"No, but the captain does."

The captain turned round as they were speaking, and Skrimshire read his secret at a glance. It was his own, discovered since his flight and flashed across the sea by the liner's pennons. Meanwhile the captain was looking him up and down, his hitherto friendly face convulsed with hatred and horror; and Skrimshire realized the instant necessity of appearing absolutely unsuspicious of suspicion.

"Mornin', captain," said he, with all the cheerful familiarity which already existed between them; "and what's all this bloomin' signallin' about?"

"Want to know?" thundered the captain, now looking him through and through.

"You bet I do."

And Skrimshire held his breath upon an insinuating grin, parrying plain abhorrence with seeming unconcern, until the other merely stared.

"Then you can mind your own business," roared the captain, at last, "and get off my poop—and speak to my officer of the watch again at your peril!"

"Well—I'm—hanged!" drawled Skrimshire, and turned on his heel with the raised eyebrows of bewildered innocence; but the drops stood thick upon his forehead when he saw himself next minute in his state-room mirror.

So he was found out; and the captain had been informed he had a murderer aboard; and detectives would meet the ship in Hobson's Bay, and the murderer would be escorted back through the Suez Canal and duly hanged after nothing better than a run round the world for his money! The thing had happened before: it had been the fate of the first train murderer; but he had taken the wrong hat in his panic. What on earth had Skrimshire left behind him that was going to hang him after all?

He could not think, nor was that the thing to think about. The immediate necessity he had seen at once, with extraordinary quickness of perception, and he had already acted upon it with a nerve more extraordinary still. He must preserve such a front as should betray not the shadow of a dream that he could by any possibility be suspected, by any soul on board; absolute ease must be his watchword, absolute security his pose; then they might like to save themselves the inconvenience of keeping him in irons, knowing that detectives would be waiting to do all the dirty work at the other end. And in two months' thinking a man should hit upon something, or he deserved to swing.

The opening day was not the worst. The captain's rudeness was enough to account for a change in any man's manner; and Skrimshire did both well and naturally to sulk for the remainder of that day. His unusual silence gave him unusual opportunities for secret observation, and he was thankful indeed that for the time being there was no necessity to live up to his popular reputation. The scene of the morning was all over the ship; yet, so far as the saloon passenger could see, the captain had not told anybody as yet. The chief mate invited him into his cabin for a smoke, spread the usual newspaper for a spittoon, and spun the inevitable yarns; but then the chief was a hard-bitten old dog with nerves of iron and a face of brass; he might know everything, or nothing at all; it was for Skrimshire to adapt his manner to the first hypothesis, and to impress the mate with the exuberance of his spirits and the utter lightness of his heart. Later in the morning he had some conversation with the second officer. It was but a word, and yet it confirmed the culprit in his conviction about the signals.

"What have I done," he asked McKendrick, "to make the old man jump down my throat like that?"

"It wasna you," replied the second; "it was the signals. But ye might have known not to bother him wi' questions just then."

"But what the deuce were the signals about?"

"That's more than I ken, Bennett."

This was Skrimshire's alias on board.

"Can't you find out?"

"Mebbee I might—after a bit."

"Why not now?"

"The old man's got the book in his cabin—the deectionary-book about the signalling, ye ken. It's my place to keep you, but the old man's carried it off, and there's no' another in the ship."

"Aha!"

"Ou, ay, it was somethin' for hissel', nae doot; but none of us kens what; an' noo we never wull, for he's as close as tar, is the old man."

The "old man" was in point of fact no older than Skrimshire, but he had worked his way aft from ship's boy, and a cruel boyhood followed by an early command had aged and hardened him.

A fine seaman, and a firm, though fiery, commander, Captain Neilson had also as kind a heart as one could wish to win, and a mind as simple as it was fair. It was on these qualities that Skrimshire determined to play, as he sulked in his deck-chair on the poop of the four-masted barque Lochwinnoch, while the captain thumped up and down in his rubber soles, his face black with thought, and a baleful eye upon the picture of offended oblivion behind the novel in the chair.

It was an interesting contest that was beginning between this pair, both of whom were strong, determined, wilful men; but one was as cunning as the other was kind, and he not only read his better like a book, but supplied in his turn a very legible and entirely plausible reading of himself. He never dreamt of impressing the captain as an innocent man; that would entail an alteration of pose inconsistent with the attitude of one who entertained no tittle of suspicion that the morning's signalling had been about himself. On the contrary, what he had really been, and what he must now doubly appear, was the guilty man who had very little fear of ever being detected, and not the fleeting shadow of a notion that such detection had already taken place.

This was the obvious and the only rôle; he had played it instinctively thus far, and need only go on as he had begun. The reward was at best precarious. It depended entirely upon the character and temperament of Captain Neilson. Skrimshire credited him with sufficient strength and sufficient humanity to do nothing and to tell nobody until the Australian detectives came aboard. But that remained to be proved. Neilson might leave him a free man all the voyage, and yet put him in irons before the very end; it would be kinder to do so at once. However, he should not do so at all if Skrimshire could help it; and he was not long in letting fall an oblique and delicate, though an excessively audacious, hint upon the responsibility of such a course in his own particular case.

It was at the midday meal, while the smoke of the accursed liner was still a dirty cloud on the horizon. Neilson remained morose and silent, while the offended passenger would not give him word or look, but, on the other hand, talked more than ever, and with invidious gaiety, to the first and second officers. The captain glowered at his plate, searching his transparent soul for the ideal course, and catching very little of the conversation; how the topic of suicide arose he never knew.

"An' I call it th' act of a coward," young McKendrick was declaring; "you can say what you like, but a man's no' a man that does the like o' that."

"Well, you think about it next time you're havin' a shave, old man," retorted Skrimshire, pleasantly. "Think o' buryin' a razor in your neck, and the pain, and the blood comin' over your fingers like as though you'd turned on the hot tap; and if you think long enough you'll know whether it's the act of a coward or whether it ain't."

"I'd blow my blessed head in," said the chief officer. "It'd be quicker."

"Oh, if it comes to that," said Skrimshire, "I'd take prussic acid, for choice. It would take a lot to make me, I admit; but I'd do it like a shot to escape a worse death. I've often thought, for instance, what a rum thing it is, in these days, that a man of any sense or education whatever should let himself live to be hung!"

The captain looked up at this; so far he had merely listened. But Skrimshire was addressing himself to the chief mate at the other end of the table; neither look nor tone were intended to include Captain Neilson, the one being averted, and the other lowered, to a nice degree of insolent disregard. On the other hand, the manner of this theoretical suicide was all audacity and nonchalance, combined with a certain underlying sincerity which gave it a peculiar value in the mind of one listener. In a word, it was the manner of a man so convinced of his own security as to afford the luxury of telling the truth about himself in jest.

"They don't give you a chance," said the mate. "They watch you night and day. You'd be a good man, once you'd got to dance the hornpipe on nothing, if you went out any other way."

"Nevertheless, I'd do it," said Skrimshire, with cheery confidence.

"I'd back myself to do it, and before their eyes."

"Poison?"

"Yes."

"In a ring, eh?"

"A ring! Do you suppose they'd leave you your rings? No; it might be in a hollow tooth, and it might not. All I say is that I'd back myself to cheat the hangman." Skrimshire said it through his black moustache. "And I'd do it, too," he added, after a pause.

Then, at last, the captain put in his word. "You would do well," said he, quietly. "I once saw a man swing, and I never want to see another. Ugh!"

His eyes met Skrimshire's, which fell deliberately; and the talkative tongue wagged no more that meal.

Thereafter Neilson was civility itself, only observant civility. He had made up his mind in the knotty matter of the suspected murderer, and the latter read his determination as he had read the difficulty which it solved, if only for the present.

"So he means to let me go loose, only keeping an eye on me; so far, so good. But how long—how long? If I thought he was going to put me in irons as soon as he sights the land—"

He looked over the side, and a slight shudder shook even his frame. It was very blue water now, the depth unfathomable. A shark had been seen that morning. And, sharks or no sharks, Skrimshire could not swim! But he had two months of steady thought before him.

Meanwhile the captain showed some cunning in his turn. He evidently wished to convince himself that Skrimshire had not suspected the signalling. One day, at any rate, the passenger was invited into the captain's cabin, in quite the old friendly fashion, for a pipe and a chat; in the middle of which Neilson left him for five minutes to speak to the officer of the watch. As the north-east trades blew as strong and true as ever, as the yards had not been touched for days, and as no sail was in sight, Skrimshire scented a trap, and presently beheld one set under his nose in the shape of the signalling-book. Skrimshire smiled. The captain found him buried in a magazine, and his little trap untouched. And the obvious deduction was also final to the sailor's mind.

Six weeks produced no change in the outward situation; but brought the voyage so near its end that every soul but one waxed merry with the thought of shore—and that one seemed the merriest of them all. They had come from the longitude of the Cape to that of Kangaroo Island in twenty days, and in all probability would enter Port Phillip Heads in two days more. In one week the Lochwinnoch had logged close upon two thousand miles; boy and man, her commander had never made such an "easting" in his seagoing life. His pleasure and his pride were alike enormous, and Skrimshire conceived that his general goodwill towards men could scarcely have suffered by the experience. He determined, at all events, to feel his way to such compassion as an honest man could be expected to extend towards an unhung murderer; and he felt it with that mixture of cautious craft and sheer impudence which made him the formidable criminal he was.

It was the night that might prove the last of the voyage, and the last night of freedom for the unhappy Skrimshire. Unhappy he undoubtedly was, for the strain of continuing as he had begun, "the life and soul of the ship," had told upon even his nerves in the end, though to the end it had been splendidly borne. To-night, however, as he paced the poop by the captain's side, he exhibited, for the first time, a despondency which exactly fitted in with Neilson's conception of his case.

"I shall never forget this voyage," said Skrimshire, sighing. "You may not believe me, captain, but I'm sorry it's over. I am, indeed; no doubt I'm the only man in the ship who is."

"And why are you?" asked Neilson, eyeing his passenger for once with the curiosity which had so long consumed him, as also with the sympathy which had grown upon him, despite, or on account of, those sinister signals' from the Castle liner. Skrimshire shrugged.

"Oh, that's a long story. I've had a rum life of it, and not what you would call the life of a saint. This voyage will stand out as one of its happiest chapters, that's all; and it may be one of the last."

"Why do you say that?"

"Oh, one can never tell."

"But what did you think of doing out there?"

"God knows!"

Neilson was miserable. There was a ring in the hoarse voice that went straight to his heart. He longed to tell this man what was in store for him—what he himself knew—but he conquered the longing as he had conquered it before. Time enough when the detectives came on board; dirty work and all responsibility would very well keep for them.

So the good captain thought to himself, as the pair took turns in silence; so the dominant brain at his side willed and intended that he should think.

"Whatever you hear of me," resumed Skrimshire, at last, "and however great a beast I may some day turn out, remember that I wasn't one aboard your ship. Will you, captain? Remember the best of me and I'll be grateful, wherever I am, and whatever happens."

"I will," said Neilson, hoarse in his turn; and he grasped the guilty hand. Skrimshire had some ado to keep from smiling, but there was another point upon which he required an assurance, and he sought it after a decent pause.

"So you expect to pass the Otway some time to-morrow?"

"By dinner time, if we're lucky."

"And there you signal?"

"Yes, they should hear of us in Melbourne early to-morrow afternoon."

"And what about the pilot?"

"Oh, he'll come aboard later—certainly not before evening. It's easy as mid-ocean till you come to the Heads, and we can't be there before nightfall, even if the wind holds fair."

"Well, let's hope it may. So long, captain, and a thousand thanks for all your kindness. Dark night, by the way?"

"Yes; let's hope to-morrow won't be like it."

But the next night was darker still; there was neither moon nor star, and Skrimshire was thankful to have had speech with the captain while he could, for now he would speak to nobody, and to-morrow—

There was no to-morrow in Skrimshire's mind, there was only to-night. There was the hour he had been living for these six long weeks. There was the plan that had come to him with the south-east trades, and rolled in his mind through the Southern Ocean, only to reach perfection within the last few hours. But it was perfect now. And all beyond lay dark.

"Isn't that their boat, sir?"

It was the chief steward who wanted to know; he was dallying on the poop in the excitement of the occasion. The captain stood farther aft: an anxious face, a red cigar-end, and a blue Tam-o'-Shanter were all of him that showed in the intense darkness. The main-yard had just been backed, and the chief officer was now on the quarter-deck, seeing the rope-ladder over the side. It was through his glasses that Skrimshire was watching the pilot's cutter, or rather her lights, and as well as he could, by their meagre rays, the little boat that now bobbed against the cutter's side.

"It is the boat, ain't it, sir?" persisted the steward.

"Yes, I think so," said Skrimshire. "How many men come with the pilot, as a rule?"

"Only himself and a chap to row him."

"Ah! You might give these to the chief officer, steward. I'm going to my cabin for a minute. Don't forget to thank the mate for lending me his glasses: they've been exceedingly useful to me."

And Skrimshire disappeared down the ladder; his tone had been strange, but the steward only remembered this afterwards: at the time he was too excited himself, and too glad of a glass to level at the boat, to note any such nicety as a mere tone.

"Four of them, by Jingo," mused the steward. "I wonder what that's for?"

But he did not wonder long: in a very few minutes the four were on board, and ascending the same ladder by which Skrimshire had gone below, the pilot at their head. Neilson received them at the break of the poop.

"I congratulate you, captain," was the pilot's greeting; "we didn't expect you before next week. Now, first allow me," and he lowered his voice, "to introduce Inspector Robins, of the Melbourne police; this gentleman is an officer he has brought with him; and my man has come aboard for a message for the shore. Mr. Robins would like a word with you before we let him go. There is no hurry, for I'm very much afraid I can't take you in till daylight."

Neilson took the inspector to the weather-rail.

"I know what's coming," he said. "The Garth Castle signaled—"

"I know, I know. Have you got him? Have you got him?" rapped out Robins.

"Safe and sound," whispered the captain; "and thinks himself as right as the bank, poor devil!"

"Then you didn't put him in irons?"

"No; I thought it better not to. He'd have committed suicide. I spotted that; sounded him without his knowing," said the crafty captain. "I happened to read the signals myself, and I never let on to a soul in the ship."

The good fellow looked delighted with himself behind his red cigar, but the acute face of the detective scarcely reflected his satisfaction.

"Well, that's all right if he's all right" said Robins. "If you don't mind, captain, I'd like to be introduced to him. One or both of us will spend the night with him, by your leave."

"As you like," said Neilson; "but I can't help feeling sorry for him. He's no more idea of this than the man in the moon. That you, steward? Where's Mr. Bennett? He was here a minute ago."

"Yes, sir; only just gone below, sir."

"Well, go and ask him to come up and drink with the pilot. I'll introduce him to the pilot, and you can do what you like," continued the captain, only wishing he could shirk a detestable duty altogether. "But I give you fair warning, this is a desperate man, or I'm much mistaken in him."

"Desperate!" chuckled the inspector; "don't we know it? It seems to have been as bad a murder as you've had in the old country for a long time. In a train. All planned. Victim in one carriage, our friend in the next; got along footboard in tunnel, shot him dead through window, and got back. Case of revenge, and other fellow no beauty, but this one's got to swing. On his way to join your ship, too; passage booked beforehand. The most cold blooded plant—"

It was the chief steward, breathless and panic-stricken.

"His door's locked—"

"He always does lock it," exclaimed the captain, as Robins darted to the ladder with an oath.

"But now he won't answer!" cried the steward.

And even with his words the answer came, in the terrific report of a revolver fired in a confined space. Next instant the inspector had hurled himself into the little saloon, the others at his heels, and half the ship's company at theirs. There was no need to point out the culprit's cabin. White smoke was streaming through the ventilated panels; all stood watching it, but for a time none spoke. Then Robins turned upon the captain.

"We have you to thank for this, Captain Neilson," said he. "It is you who will have to answer for it."

Neilson turned white, but it was white heat with him.

"And so I will," he thundered, "but not to you! I don't answer to any confounded Colonial policemen, and I don't take cheek from one, either. By Heaven, sir, I'm master of this ship, and for two pins I'll have you over the side again, detective or no detective. Do your business and break in that door, and you leave me to mind mine at the proper time and in the proper place."

He was furious with the fury of a masterful mariner, whose word is law aboard his own vessel, and yet beneath this virile passion there lurked a certain secret satisfaction in the thought that the companion of so many weeks was at all events not to hang. But the tragedy which had occurred was the greater unpleasantness for himself; indeed it might well lead to something more, and Neilson stood in the grip of grim considerations; in his own doorway, while Robins sent for the carpenter without addressing another syllable to the captain.

The saloon had been invaded by steerage passengers, and even by members of the crew, but discipline was for once a secondary matter in the eyes of Captain Neilson, and their fire was all for the insolent intruder who had dared to blame him aboard his own ship. The carpenter had to fight his way through a small, but exceedingly dense, crowd, beginning on the quarter-deck outside, and at its thickest in the narrow passage terminating in the saloon. On his arrival, however, the lock was soon forced, and the door swung inwards in a sudden silence, broken as suddenly by the detective's voice.

"Empty, by Heaven!" he shrieked. "Hunt him—he's given us the slip!"

And the saloon emptied only less rapidly than it had filled, till Neilson had it to himself; he stepped over to the passenger's cabin, half expecting to find him hiding in some corner after all. There he was wrong; nor did he at once grasp the full significance of what he did find.

A revolver was dangling from a peg on one side of the cabin—dangling by a yard of twine secured to the trigger. A few more inches of the twine, tied to the butt, had been severed by burning, as had another yard dangling from another peg at the opposite side of the cabin. An inch of candle lay upon the floor.

The twine had been passed through it: there was its mark in the wax. The whole had been strung across the cabin and the candle lighted before Skrimshire left; the revolver, hung by the trigger as a man is hanged by the neck, had been given a three-foot drop, and gone off duly as the flame burnt down to the string.

Such was the plan which an ingenious (if perverted) mind had taken several weeks to perfect.

Neilson rushed on deck, to find all hands at the rail, and a fresh sensation in the air.

The pilot met him on the poop.

"My boat's gone!" he cried. "And the night like pitch!"

Neilson stood thunderstruck.

"Did you leave a man aboard?"

"No; he came up for a telegram for the police in town."

"Then you can't blame me there."

And the captain leapt upon the rail at the break of the poop.

"Silence!" he roared. "Silence — every man of you! If we can't see we must listen... that's it... not a whisper... now..." At first there was nothing to be heard but the quick-drawn breath from half-a-hundred throats; then, out of the impenetrable darkness, came the thud, thud, thud of an oar in a rowlock, already some distance away; but in which direction it was impossible to tell on such a night.

The Lady Of The Lift

It was the Man from Winchester who gave her that name: the Man who was Swiss godfather and godmother to half the hotel. Whiskers and the Suffragite, the Meenister and the Limit, were a few more of his baptismal efforts; but it is only fair to state that he called us these things behind our respective backs, whereas we called him Man to his impudent little laughing face. The one exception to a redeeming rule was the Lady of the Lift, who delighted in her nom d'hotel and made much of its inventor. The Man was in fact a sufficiently healthy and hearty specimen of the young barbarian; but though doubtless a very small molecule at Winchester, where he had but finished his first term, it must be confessed that there was a good deal of him at the Alpine haunt to which his people had brought him for the Christmas holidays.

It was one of those spots to which half one's friends flock nowadays in the latter part of December, to return with the complexions of Choctaws all too early in the New Year. A group of gay hotels, with as many balconies as a pagoda, and an unpopular annex in the background, had broken out upon a plateau among the dazzling peaks. Snow of an almost incandescent purity and brilliance rose in huge uncouth chunks against a tropically blue sky; the softened shapes of mountains lay buried underneath; and snow clung in great gouts to the fir-trees, that bristled upon the lower slopes like darts from the blue. You had to freeze for hours on a sledge, skimming dizzy ledges, climbing all the time, to reach this fairy fastness from the nearest railway. But it was worth the freezing, even before the journey's end, if you made it by moonlight, as just before Christmas one did. And the hotels when you reached them (if only they really had reserved those rooms) were quite wonderfully managed and equipped: surely there are volumes in the fact that there was a lift in even one of them, a lift with a crimson velvet seat, where a poor lady could sit and watch the fun at nights, of it but not in it, and so not in the way at all, though accessible to chivalry not otherwise engaged.

The poor lady! That was her life in the hotel; and everybody was sorry for her except herself. It seemed such a sad-case. The exact trouble was unknown—she never spoke of herself—but its outward sign was a crutch. And her face was so young, and her hair so gray! But younger than her face was the whole spirit of the Lady of the Lift: her humor, her courage, her breezy outlook on life, her keen interest in everybody and everything. And the cruel part of it was that nature had cast her in athletic mould, that in fact she had excelled at those very sports which she was now constrained to watch at a distance from the bedroom balcony where she took her modicum of open air.

Madame Faivre she was called to her face; and her English was just a little broken. But who she had been formerly, who or what her husband, or any other detail of her sad life, nobody knew or even pretended to know, with the possible exception of old Whiskers, and he was both vague in his ideas and chary of expressing them.

Old Whiskers, so dubbed by young Winchester on account of a somewhat feline or Teutonic moustache, was an Alpine veteran who climbed in summer and curled in winter. He was understood to improve the equinoxes in some scholastic capacity at Oxford. The personality of Madame Faivre quite worried Whiskers for a day or two after his arrival; he could have sworn that he had met her somewhere, and so he told her with the easy modest sociability which made him another favorite himself.

"It was before I gave up skating," said Whiskers. "I can't help feeling that we've skated together, somewhere or other."

"It must have been many years ago," said madame. "I also have given it up quite young. I have had a weak ankle. I have to thank that ankle also for this crutch."

Whiskers felt embarrassed. He was in fact the first to be informed that the lady's infirmity was originally due to an accident; but he kept the information to himself, and discussed Madame Faivre no more with his hotel acquaintances. He felt he had already committed a minor breach of tact and taste; he made amends with many little deferential attentions; but still the vague memory, the elusive association, would cause him a certain amount of mental exasperation whenever they met, as a riddle of no consequence that yet refused to be given up.

Then an old skating friend turned up, and was turned away, without so much as seeing the rooms he had engaged seven weeks before; but he did insist on having his lunch, and parenthetically he solved the mystery for Whiskers at a glance.

"Remember her! Why, of course I remember her; don't you?" And he whispered the maiden name for which Whiskers had racked his brain in vain.

But Whiskers was getting to the age at which memory begins to fail; he was not immediately the wiser.

"I seem to remember the name at Davos one year," he said. "Or was it St. Moritz?"

"Davos. I should think you did remember it!"

"Why?"

"Well, for one reason you used to skate with her every day; you were about the best pair there."

"So I told her!" cried Whiskers.

"You don't mean to say she denied it?"

"Certainly; no recollection whatever, so she said."

The old skating friend came up to Whiskers's good ear. They were waiting in the hall for lunch, and the lady as usual was waiting in the lift, had indeed gone up and down in it more than once rather than relinquish her favorite seat. But now she hung at anchor a few inches above the level of the hall, exchanging the sprightliest and kindest glances with all the hungry, bright red faces, just in from sun and snow.

"Of course you know why she denies it?" whispered the old skating friend.

"I suppose she's forgotten me too."

"Not she!"

"How long is it ago?"

"Seven or eight years, I suppose."

"That's it, then; we've both aged."

"She has, if you like!" said the skating friend. "She looks twenty years older—might be another woman altogether—but she isn't, by Jove! Don't look, but she's got her eye on us now."

She had, though she was rallying her young Man at the same time, and he her with perfectly unintelligible Winchester repartee. Whiskers begged his friend to refresh a treacherous memory.

"Well," began the other, "it was such a terrific scandal at the time..."

Whiskers did remember the whole thing. It made him grave. His friend, about to be turned back through the snow, vowing an Englishman's vengeance in the Times, and really only distracted from his grievance by seeing and hearing about the Lady of the Lift, now took a mordant satisfaction in pouring vitriolic comments on the forgotten scandal into the good ear that Whiskers was lending him perforce. That ripe gray scholar listened grudgingly; more than once he begged for a lower whisper; and it was through him that the pair stayed behind in the hall when all the rest had trooped off to luncheon.

"It's a good many years ago," the old boy said. "She must have married and settled down since then, and had a hard time of it at that, I'm afraid; it's most awfully bad luck our crossing her path like this. She shall never know I spotted her. Women should always have another chance. And this one has been smashed up into the bargain: an accident, I gather: probably one of those infernal motors. I must look after her a bit more. Remember her? Do you remember her rocking turns and three-change-threes?"

Old Whiskers was as good as his word; at least he was as good to the poor lady as she would allow him to be. Now he remembered her better every time he saw her, and marvelled more and more at the change which a few short years had wrought in her. At sixty he himself looked to all intents and purposes as good a man as he had been at fifty-three; the salt had gained upon the pepper in his hair and moustache; his mirror advised him of no graver change. Yet here was a fine athletic girl transformed into a decrepit elderly lady in little more than a lustrum. Nemesis had handled her very roughly; her present case was sufficient punishment for any past, even for that which seemed incredible when one looked upon the bright young smile under the beautiful silver hair. Old Whiskers was not sure but that it was an improvement, that hair!

It was about all he saw of Madame Faivre for a day or two; she held her nightly court in the lift when the young people were dancing in the hall, but the next time her elderly admirer approached she seized the lever herself and shot straight into the upper stories. He was waiting for the lift, however, if not for her, when she came floating down again with a book, and by means of an adroit compliment he got her to take him up again for his pipe. Nor did he immediately desert the lift in favor of younger blood on their return to the hall level.

"My waltzing days are over," said he, with a cunning sigh, as they looked out over the dancers, he loading his pipe particle by particle with pauses in between.

"So are mine," said she, falling into the trap set for her sympathy.

He looked at her with a kindling eye.

"Ever waltz on the ice, Madame?"

"Very badly, half a century ago!"

He laughed politely. "Ah! that's dancing," he said; "it makes all this sort of thing look silly."

The pipe got itself slowly, very slowly, loaded while he bragged about his own skating without asking any more questions about hers; until just as he was going, match in hand.

"Ever try a rocking turn?" he said.

"Never," she smiled, confidently.

"Or a three-change-three?"

"No."

"No more have I," he said, "for about a century by your reckoning, and I suppose I never shall again."

It was all very wanton, and at first he could not think why he had done it; but a little intellectual probing transfixed the reason in due time. It was not the romance which the knowing Man detected with such glee, and reported with strange epithets to his particular friends.

Whiskers was not that kind of old fool; neither was he a crabbed bachelor with "no use for" the average woman. He could talk to her, on the contrary, with extreme cleverness and vivacity if she had any brains at all, with a hard sparkle in the worst of cases. He would even reason with the Suffragite. He liked talking to Madame Faivre; he would have loved madame to talk to him. He might have helped her. He heard himself sympathizing, advising, bracing her with advice. There was no woman in his life who had any need of his advice or sympathy. He had broad ideas, a generous judgment of all but intellectual shortcomings; he would have been glad to show himself in those colors, for they were his true ones, though he had seldom had a chance of running them up on the high seas of life.

That was all; it was a fairly frequent thought, never an obsession. Whiskers was out to enjoy himself, and he did that daily and hourly on the rink. He had given up skating, as he said, but he had taken to curling, and he loved the game; it appealed to his intellect and humor; he would caper like a boy, would "soop up" like a good Galloway Scot. His daily foe was the Meenister; the Meenister cur-r-r-r-r-led. Watching them in twinkling skates and grubby sweater, the volatile figure of the small Wykehamist might be seen a mile off; it was worth skating that way to note his impudent little nose creased up in delight at dialogue and antics alike; luckily the little devil wasn't there on the dreadful day when the Meenister used a much worse word!

The one to spread that scandal was the Limit, a swarthy plutocrat blessed with the most olive of olive-branches, whom the Man nevertheless described as "a hectic crowd." The Limit wore rings on his fingers and diamonds in the rings. The Limit had the most extensive wardrobe in the hotel, and Mrs. Limit glittered all over like a jeweller's window at table-d'hote. These statements seem due to a natural talent for nomenclature which was usually apposite and often inoffensive.

The whole party, despite a capacity for internecine strife latent in several of the tithe who have now been mentioned, got on admirably together until the second week in January, when the weather played them false. It had been ideal up to then: hard blue skies, hard black frosts, and no more snow. Everybody slid everywhere on a luge, or dragged it cheerfully up the hill; bob-sleighs were in favor, but the place had not risen to the perilous luxury of an ice-run for true tobogganing. There was dancing every evening in all the hotels; there was even a combined fancy-dress ball, at which the Man—but enough of that valued contributor to the general gaiety. The thing was a success. The Lady of the Lift, who never left it all night, provided the only memorable instance of plain clothes; she made no change from the black crepon skirt which she wore day and night, with now one upper garment, now another; to-night it was merely the jet bodice of most nights, and yet Mrs. Limit in all her diamonds was often a lonely figure, but there was always a bevy about the lift.

That night the snow began. The next day it never stopped. The rink was covered, swept, covered deeper than ever, and finally deserted by disconsolate meenisters, scholars, and skating tag-rag. Because the London papers had never been so keenly desired, the afternoon sledge never came up with them; luckily there was a telephone to allay anxiety; luckily, indeed, for every reason. It was already the one remaining line of communication with the outer world. The mountain road was practically obliterated by the snow. The very contour of the mountains seemed more generous, less angular. The snow fell straight and thick as rain from a windless sky, in tiny flakes. It stuck everywhere, followed the minutest shape of everything, bent the slenderest twig under a coating three times its own thickness. It turned the telephone wires into thick white ropes that you lost against the roof from which they sprouted, but followed for miles against the darkling pines. The Limits played bridge, the Man was sadly spoiling for Winchester, the admirable Whiskers set about organizing an afternoon entertainment, and the Lady of the Lift told fortunes there for a local charity.

She was the life and soul of the place while things were at their worst, the witch who drew her children round her like the Pied Piper, only without piping, by just being herself and making play with a pack of cards and her own simple ready wit. Her hands, it was noted in this connection, were as smooth as her face; and the cruelty of the affliction that so aged her was more than ever emphasized by the splendid spirits which she not only maintained herself but infused into many of the most dejected sportsmen of both sexes.

But she grew paler under the strain; she had her very meals in the lift, despite draughts and cold; and after luncheon on the second day they found her there fast asleep.

"Why persevere in this extraordinary eccentricity?" asked old Whiskers in quite a fatherly fashion. "To sit in a chilly lift by the hour together! Where can the fun come in?"

"I do it not for fun," she said.

"Then why do you do it?"

"Cannot you guess?"

"You used to say it was to see what was going on."

"It was true."

"But nothing has been going on to-day, except your own most philanthropic sideshow."

"I know."

"Then why conduct it here? Why not transfer your court to a warm room?"

She smiled faintly.

"Could you keep it to yourself if I told you?"

"I won't give you away, Madame!" he exclaimed with some cordiality.

"It's because—by remaining in the lift—I—I have only one walk—to and from my room!"

He was horrified; she saw that he was, and signalled to the lift-boy.

"I will take your advice," she said, "and go to my room perhaps for the rest of the afternoon, if it has also finished to snow. Thank you very much for all your kindness." And up she went out of his ken, smiling down upon his blank upturned face.

It really had "finished to snow"—for the time being. That was why poor old Whiskers had come to have the Lady of the Lift to himself even for five minutes. The young people had all trooped out to see what could be done. It was just thawing. The Man shot a snowball with deadly aim at a young Limit, who ran off yelping to papa over his cigar and cognac in their private sitting-room.

The missile had travelled like a cricket-ball till it went asunder on the nape of little Limit's neck, which it ran down like a waterfall.

The snow was declared to be "absolutely plumb" by the expert author of this dastardly attack; but the sky was black with more snow that might begin falling any minute. If an attack was to be made upon any or all of the other hotels, or a pitched battle fought with them in the open ("an' what for no?" cries the worthy Meenister), there's no time to be lost in manufacturing a casus belli (as Whiskers puts it), but a bloodthirsty challenge must be despatched at once. Budding Winchester takes it on his skis; he is not a Man any longer, but a boy of boys, his face flushed and his eyes shining for the fray.

It comes on in incredibly few minutes. All are eager after it. A combat of the true Homeric type is soon raging in the snow; the aggressors become the defenders before they know where they are, or rather why they are back upon their hotel terrace. It is because the smaller hotels have converged upon them from three points of the compass. Hurrah! Three cheers for the Beau Site and Winchester! A bas Kurhaus—Belvedere—all the rotten lot!

Grand how the young boy hurls taunt and insult with his explosive cricket-balls; grander still to see "the old birds," "the old pets," "the stone-age gang," as he has called them behind their backs, shying, shouting, ducking, dodging with the best. Old Whiskers has not loosened some muscles so freely since cricket gave him up.

The Suffragite is naturally to the front, and "Votes for Women!" becomes the bad boy's cry. He may say what he likes to anybody now. He has wiped out all his sins by bringing about this glorious battle, by his own heroic bearing in the van.

"Good shot, Daddy!"

"Look out, Mummy!"

That's the little dog both times; they will make something of him at Winchester yet. This is his show, remember! "I began it," he may boast all his days; for the least likely, the meekest, the quietest, the most stay-at-home-by-the-fire, all were in it before the end. O that Meenister! There were those who vowed they heard him railing to himself against "you deevil," a prominent opponent, as he squeezed the snow from his beard. Even the unworthy Limit gathered great handfuls on his sitting-room balcony, where he and his were impregnably ensconced, and hurled them down like rocks upon the foe....

And the whole thing has nothing whatever to do with the Lady of the Lift!

But the immediate sequel had.

In the first place they were asked not to make more noise than they could help, when they came in tramping and shouting, and some of the invaders with them for a drink. Madame Faivre had taken to her bed. She only begged not to be disturbed. But the good maître d'hotel would have taken upon himself to telephone down for a doctor; but there, what could you expect in such cold weather? The telephone had broken down. No; it was no use trying the other hotels; his was the main wire, of which they were mere extensions. The whole humming, glittering plateau was cut off from the world. As well cross the mountains on skis, and drop down into Innsbruck, as risk an avalanche on the precipitous pass down to the railway miles below; for the first exploit infinite knowledge and experience of the country would be requisite, for the second an infinity of good luck.

The entire crowd were in the fine big hall or lounge, their tanned and burnt faces glowing like lamps in the dusk, their voices hushed with one consent. It was sad to see the lift standing empty. None entered it, though many must have wished to sit down aloof, and more to be spirited upstairs. There was a consensus of vague feeling about it, and a well-known voice could be heard piping quite respectfully: "Poor old girl! She had her agony duck on all the morning!" Those who want to know what he meant had better apply to his alma mater.

Suddenly a bombshell burst on the assembly.

"Herr Breitstein! Herr Breitstein!" It was the Limit flying down the stairs. "We've been robbed, sir, robbed of everything in your confounded hotel, confound you!"

" 'Sh! 'sh! 'sh!" went Herr Breitstein, as sharply as the sound allowed. "There's a lady ill upstairs."

"Confound the lady!"

"Shame! Shame!" And a treble voice: "Didn't I tell you he was the Limit?"

"Well, she's probably been robbed as well," said the Limit, finding himself an unpopular figure on the stairs. "I advise everybody with valuables to go and see to them; we've lost all ours, and they were worth something, as you know."

This took three or four ladies upstairs apace, including the Winchester mamma.

A mechanic appeared with a little bag while they were gone, and began talking German to mine host.

"Herr Je!" cries the good man, excitedly. "Do you know what he tell me, shentlemen? Our telephone wires have been cut, mit some sharbp imblement, on ziss side of ze inzulador outside ze top bad-room vindow!"

Imagine the twin wires, thickened into ropes of snow, vanishing and reappearing against snow and trees for miles and miles, looking like live rails back to the world, yet being dead all the time!

The three or four anxious ladies were back upon the stairs behind the Limit before useful comment had emerged from the general consternation. They also had each lost something—a watch—a bracelet—a garnet necklace—whatever of any value they had left behind them in their rooms.

"But my little lot are worth about fifteen 'undred quid," cried the Limit, loudly.

Nobody bid against him; but the good landlord again very properly checked the vociferous tone employed, repeating his reason on poor Madame Faivre's behalf. The name struck the lift-boy, struck a spark of memory that lit him up like a lamp. He struggled toward Herr Breitstein with roseate cheeks, and had his ears boxed for his pains the moment he ceased gabbling.

"Do you know what he tell me, ziss wretched poy? He zee a voman come out of ze room of Madame Faivre—fine young voman—ze tief, shentlemen, ze tief if she haf not also murdered madame!"

Up they rushed in a breathless bevy. There was no answer to their knocks, their hammering, their united shouts. The mechanic was called up to pick the lock; mine host was not going to send good money after bad blood. But no blood had been shed; no madame was there; but her crutch was, and her crepon skirt, and the jet bodice among others...

It was the Suffragite who put the whole case beyond doubt. She disappeared suddenly, was back in a minute, and broke in breathless:

"I know what else has gone—my skis—and she always told me they were the best in the hotel!"

There was a shocked pause, hardly broken by a really carefully whispered: "Votes for Women!" It was poor Whiskers who spoke the first word aloud.

"Good God!" said he. "And I'd quite forgotten she was as good on skis as on skates!"

They turned on him like one man.

"Did you know her before?"

"Where did you know her?"

"What do you know about her?"

"I met her once at Davos years ago."

"Davos!" cried mine host. "Zey had such a case zere in 'ninety-nine, shoost such a case, shentlemen!"

"Oh, did they?" says Whiskers without a blush; and that was all he ever did say on the subject.

But the Man from Winchester is fairly entitled to the last word; it took him some time to think it out, and his hearers come to see his point.

"On the whole," said he, "I wasn't so far wrong, was I, when I called her the lady of the lift?"

The Man At The Wheel

Oswald Alfred Smart had been christened, (by permission) after the suburban magnate to whom his father was coachman at the time of the urchin's birth; and the two names went so well in double harness, as the coachman said, that they were never heard singly about the stables, although Mrs. Smart was very particular to say "our" Oswald Alfred, even when employing: the vocative case, in respectful contradistinction to the master. Both Mr and Mrs. Smart seem to have had their work cut out with the boy, who often had a stick about his back for his hot yet sullen temper, which was not cured by the treatment. He had, however, from his earliest years, when his better side was uppermost, a smile so sunny and so sudden as to transmute his leaden look to radiant gold. And it was largely this smile which got Oswald Alfred his engagements when, as a son of the house remarked, he "put the lid on" a consistently unfilial attitude by turning chauffeur at the first opportunity.

The old coachman, who knew the lad's temperament, though his knowledge of motor-cars was confined to keeping his carriage out of their way, enjoyed a gloomy view of the venture from the first. His confident misgivings were amply realized. Oswald Alfred's hot head lost him more than one situation in the first year, but not before he had cost successive employers large sums in fines and repairs, because they liked him for his eager alacrity and always hoped he would improve. His smile never failed to secure him a fresh start elsewhere; and as his sins were not due to lack of skill, but were purely a matter of nervous temperament, he went on better than he deserved until a really bad accident got into all the papers and ought clearly to have closed a dangerous career.

Old Smart was sanguine that it had, and made dogmatic computations as to what was not worth fifty bob a week; his attitude was one of chastened superiority on half that preposterous wage. But Oswald Alfred had not gone home after his other vicissitudes, and he was not going now to afford an object-lesson in accurate parental prophecy. He preferred to eat his heart out in his Shepherd's Bush lodgings—as long as his savings lasted, and sometimes even to squander them in defiant jaunts involving a very high collar and a rakish cigarette. But his luck held good, by returning before his pockets were quite empty, in the shape of a promising reply to his own reply to an advertisement for a chauffeur who "must be young man."

The young man invested in a higher collar than any in his now shabby stock, and slept on his best trousers before betaking himself to a Bloomsbury hotel to meet the gentleman with the funny name who had written to make the appointment. The gentleman had rather a funny face as well, dark and sallow, with eyes like chocolates; but there is never much light in Bloomsbury, at any rate in the month of February, and Oswald Alfred was not going to belie his stable upbringing in the matter of a gift-horse; for he had a shrewd suspicion that it was "all right," from the first funny accents in keeping with the whole personality of the advertiser, and of a piece with the curious locution (which the applicant had not noticed) in his advertisement.

"So Smart is your name, young man! Smart of name and smart of nature, is it not? Mine, as you know, is Ghum; by Ghum it is, like you say in the classic! I am very glad of you to swear by me, young man."

Oswald Alfred was merely embarrassed by these familiarities, for he had the instincts of a British servant in every vein, and had no desire to be treated otherwise in his new employ. His skin turned a dusky red, which deepened when Mr. Ghum displayed a startling knowledge of the accident which had cost him his last place.

"We spot it in the morning rag," the dark gentleman explained, with a show of teeth and an increasing air of idiomatic mastery; "we remember your name, and have wonder if we might hear of you. How have come you to meet such serious accident, young man?"

Oswald Alfred leaned forward from the edge of his chair, and stated his case to the lining of his cap as even he had never stated it before.

"It was like this, sir: I'd been to meet my lady and gentleman at Victoria Station (London, Chatham and Dover, sir); and the boat was very late, you see, and they'd brought over a new French maid who'd never been in a car before; an' that's 'ow the 'ole affair come to 'appen, sir. It was a limousine, sir, forty-'orse Feeut, an' that piled up with luggage we was absolutely top-'eavy; but my gentleman, 'e was always saying 'is car cost 'im quite enough without cab-fares over and above. I used to tell 'im 'ow it'd be some skiddy night, but he wouldn't take a word, though he'd a rough enough side to 'is own tongue, and I'd decided to give 'im notice when it 'appened in Sloane Street on the way 'ome that night. I was coming along at a good pace, but not exceeding, an' the only other thing in the street was a tradesman's van same way; 'im on the near side, sir, and me coming up on the crown, and blowing my horn. Suddenly he pulls right across me without ever 'olding out 'is 'and; right across me into Pont Street, without showing a finger! There was only one thing to be done, and I done it; took the corner myself, instead o' crashing into 'im, an' beat 'im round it, too! But with all the grease on the road and all that luggage on top we skidded somethink cruel, and took the pavement and smashed our near door against one o' them posts that are there to smash you. My lady and gentleman weren't hurt, they can't say they were, nor yet the worse off anyhow, being insured. But the girl, she'd never been in a car before, an' there she set beside me in front; it wasn't 'ardly right, sir; she didn't know enough even to 'old on. Out she went an' got concussion, and I lost my place for that!"

"A thing you could not help?"

"A thing I could no more help," declared Oswald Alfred, "than the babe unborn." The chocolate eyes regarded him with sleepy benevolence. "It was hard on as young a man like you," said Mr. Ghum.

"It was very 'ard, sir."

"You deserve another opportunity."

"I should be very grateful if you could give me one, sir."

"And you would not find awful traffic our way," Mr. Ghum added, as though the statement contained a joke; but the subject was no joke to Oswald Alfred.

"I'm not afraid of traffic," he boasted with perfect truth; "but when 'orse-van drivers don't 'old out their 'ands they ought to be put in prison."

"On the other end of the equation," continued Ghum, soaring high over his hearer's head, "you would have a very invaluable life committed to your keeping. I would not be your master, but your master would be mine. I am not interviewing with you on my own account, but as the representative of one of the native big-bugs of my country, who is spending a little holidays in your old one."

Oswald Alfred had pricked up the ears of a keen and catholic sportsman; in fact, the newspaper of that name was even then folded carefully away in the pocket in which it was least likely to spoil the cut of a coat.

"Kind of Jam, or something?" he inquired with interest.

"Exactly! Quite! You hit it on the nail! His Highness the Jam Sahib of Boavista—my royal master and yours who is to be!"

An ill-concealed levity rather spoilt the effect of this descriptive mouthful on Oswald Alfred, but was soon forgotten in his joy over the terms that he succeeded in making for himself. It was wonderful how amenable Mr. Ghum proved to reason and Oswald Alfred's best smile. The lad had been getting fifty shillings in his last place, but of course keeping himself; in the new one he was promised forty and all found. It was not perhaps quite the kind of arrangement that a more independent chauffeur would have been so ready to entertain, but the financial improvement was such that he would soon be in a position to pick and choose again, unless he went and got into fresh trouble through the criminal negligence of others on the road. He was determined it should be through no fault of his own; and the old coachman himself could not have excelled his son in distrust of other drivers on the day that Mr. Ghum called for him with the car in Shepherd's Bush.

The car, a sound second-hand Cleland-Talboys, had been driven thus far by a chauffeur from the works in Notting Dale, where it had been some days undergoing repairs. Oswald Alfred very properly sought particulars, and the works' chauffeur was saying that so far as he knew there had been nothing at all the matter with her, when Mr. Ghum closed a promising discussion by inquiring if Smart could find his way to the Portsmouth Road.

"Then the sooner the better we are on it," he said curtly on getting an affirmative reply. "The car has been tune up for you, like they say in the classic; let me hear her melody without delay. Straight along the Portsmouth Road—but mind you traps—and when we arrive near Guildford I will give you direction."

It was one of those bitter afternoons which make the early spring for, days together as cold as the depths of winter, and even colder to the eye. There was no sun in the bleak sky, and no rain in the clouds that flew there, but the trees looked black and brittle against both, and ploughed fields cold as new graves behind the trees. Telegraph posts stood along the side-strips of bleached grass, like sentinels frozen at attention, but here and there a live scout saluted with his reassuring grin. Mr. Ghum sat and shivered behind the windscreen in a coat like a dancing bear's; and the warm young blood at his side did dance with the delight of rattling along an open road again, and that without interference or complaint. Mr. Ghum raised no objection to thirty-five miles on the speedometer, nor yet to taking a corner on the wrong side or bucketing over patches of new metal, all of which were old tricks of the new chauffeur. If the Jam himself was as sensible it might be a pleasant place both on and off the car.

And a pleasant place it proved, at all events in the way of creature comforts and letting a man alone at his job; but Oswald Alfred did speedily find himself lonelier at other times than suited his habit as he liked to live. This again was a mere effect of causes in themselves both strange and disagreeable. There wasn't a female in the house, for instance; dusky heathen shuffled about the kitchen, and the newcomer's was the one white skin on the premises. Dusky heathen jabbered and guzzled in drawing-room and dining-room, and fresh relays were always being taken to the station or met there by the car. So it all seemed to Oswald Alfred. There was room for any number of the savages, as he himself was savage enough to call them in his heart; for the house had been formerly a preparatory school, and there were beds still in the dormitories, whither and whence the chauffeur was too often prevailed upon to carry weird bits of baggage. There were empty class-rooms, too, that gave him a chill when he passed their neglected windows. Yet it was a pretty house when the sun shone on its red brick and tiles, and its modern leaded casements, all so racy of the Surrey soil that surrounded it with sombre cedars and with yew hedges no longer of rectangular cut. The chief drawback was that it was a long way down a lane, which was a longer way down another lane; in fact, a more precious-spoken Oswald Alfred might have characterized the place as an oasis of bricks and timber in a wilderness of bracken and gorse..

Our Oswald Alfred confined himself to phrases like "the back of beyond," except on the subject of his never being allowed out anywhere alone, which moved him to the ruder eloquence of his old stable days. He never knew when his car might not be wanted, and was always expected to be on the spot himself in case of emergency. Of course he would never have stood it, had it not meant a steady saving of two pounds a week, and a "chit" (which was Mr. Ghum's synonym for a "character") whensoever he elected to leave of his own accord. But the youth was so well boarded and lodged (in what had been the sick-house of the departed school), and such was the consideration shown him in smaller matters, that he wisely resisted any inclination to make another change before the summer.

His Highness the Jam Sahib of Boa vista (a name painted, curiously enough, on the garden gate) was the only member of the strange establishment to whom the new chauffeur took a real dislike; and it was not justifiable, inasmuch as the Jam never vouchsafed a word to him in praise or blame. He had a lean, mean face and figure, in striking contrast to his courtier Ghum, who was gross and genial; but it was the subdued ferocity with which his Highness would let his followers have it, in their own lingo, that made Oswald Alfred bustle before the ruthless lips had time to open fire on him. He gathered from Ghum that the potentate was leading his present quiet and modest life under doctor's orders and the sympathetic ægis of the Imperial Government.

Motoring was stated to be part of the treatment, and yet they did not motor daily, nor on the likeliest days, nor yet always when the chosen day was at its best. Often it would be the latter part of a dismal afternoon before Oswald Alfred went skidding through the muddy lanes with the burly Ghum beside him, his Highness and minor satellites abreast behind, and the acetylene head-lamps duly primed by order; for the Jam and his suite, did not dissemble a natural kindness for dusk and darkness. Neither did the white youth object to either, or even to the crew, he drove, when he was driving them; for they none of them interfered with him any more than Mr. Ghum had done, but let him go like the wind in the shortest of clear spaces, and cram on the brakes to his heart's content at the corner; so refreshing was their freedom from the little knowledge which is the abominable thing from a chauffeur's point of view. Ghum, however, was by way of acquiring some, but only from Oswald Alfred, who gave him indifferent driving lessons with little method and less regularity.

The party usually drove one way; but it was the most obvious way in the geographical circumstances. Guildford and Godalming ought to have been able to pick out the second-hand Cleland-Talboys even from the band of cars that flows over the flywheels of their main streets from dawn to dark; it was never quite dark when they clattered through to fly Hindhead like a hurdle; but they always lit up about the same place, just off the Portsmouth Road in the neighbourhood of Liphook. Here may be found, one of those impressively extravagant, because solid and interminable walls, which are by no means such a feature of the home counties as of the shires. Yet there was a point of this noble circle which was no great distance from the worthy pile within; the drive was not a long one; and a side gate, which came first, afforded a still shorter cut to the house.

It was through this gate that the motorists, on foot for the purpose, were peeping, one lighting-up-time at the beginning of March; and Oswald Alfred, attending to his own business with a box of matches, was taking as little interest as usual in theirs. He had gathered, from remarks dropped in Ghum's English, that H.H. had his royal eye on the place as a more fitting English seat than the deserted school; but he had no idea to whom it belonged. Suddenly a bicycle bell rang out between him and the peeping gentry at the gate, startling them more than himself, and causing an obsequious pantomime on their part in honor of the elderly gentleman who had jumped off the bicycle. Oswald Alfred was particularly impressed to see the Jam Sahib-making as deep an obeisance as the youngest of his followers; he could only suppose they had been surprised by some very great personage indeed.

"Good evening, my friends!" cried the cyclist in a rich, kind voice. "Come to have another look at my kangaroo, have you?"

"Sir," replied the Jam, bowing lower than before, "some of these gentlemen had not the felicity of being present on the occasion to which you graciously refer. I was therefore taking the audacious liberty—"

"Nonsense!" interposed the cyclist, heartily. "You take 'em in and show 'em anything you can by this light, and I'll trundle on to the lodge and join you at the sub-tropical kennels with the keeper. My poor beasts have felt the winter as much as you and I have, I'm afraid; but we shall go back to the sun refreshed, and they never will, poor devils! Hurry up, or I'll be there before you!"

This in a genial crescendo as the four forms debouched through the gate and melted fast into the gloaming. Meanwhile Oswald Alfred was marvelling to find that after all his Highness could speak better English, when it suited him, than any of his retinue, and yet that his tone did not sweeten with his words. His tone had been bitter and truculent in some curiously subtle degree, which incurred no snub yet could penetrate the patriotic hide of a British coachman's son, and inject the virus of a vague resentment. Next moment the cyclist was giving his natural enemy the chauffeur a kindly word as well, and in the twin cones of acetylene gaslight the chauffeur recognized his great man at a glance.

"Good evening, my lord!" returned Oswald Alfred, with ready salute and the smile which had lain fallow at Boavista.

"Have we met before?" inquired the other in a tone both puzzled and amused.

"No, my lord, but I see it was Lord Amyott as soon as ever you come in front of, the lamps. I seen your lordship's portrait many a time when you was out at the war."

There was genuine enthusiasm in this speech, for Oswald Alfred had a nice capacity for discriminating respect, inherited from the parent who had insisted on so christening him after the master. Lord Amyott, however, did not seem particularly flattered, and his wiry white moustache looked closer-cropped than before on its granite pedestal of chin.

"Ah, well, I'm in another part of the empire now," said he, "and only home for a few weeks, like our friends from the same place." He jerked his head toward the gate through which they had gone, and then stared harder at Oswald Alfred. "You ain't the chauffeur they had the other day?" he added.

"I've been in my situation a fortnight, my lord," was the considered reply.

"Do you know what happened to the other fellow?"

"I never 'eard, my lord."

"No more did I, and I should like to know. Nice-lad, I thought him." Lord Amyott stepped up nearer to the bonnet, and lowered his voice. "Do they ever let you out of their sight?" he asked, grimly, but as though it were rather a joke as well.

"Never off the premises, my lord,"

"They never let him! I suppose he couldn't stand it. But I should like to know."

Oswald Alfred was not to be outdone in dramatic undertones. "It's all the Jam!" said he sepulchrally.

"All the what?"

" 'Im that spoke to your lordship; his Royal Highness the Jam Sahib," explained Oswald Alfred, feeling that he was indeed moving in exalted circles, and unconsciously adding to the altitude. But Lord Amyott only burst out laughing under his breath, after catching it in sheer surprise.

"Does he really call himself that?"

"Only in fun, my lordship, only in fun!" urged a silky voice; and the oleaginous Ghum stood fawning between the speakers in the acetylene rays; how he had returned without a sound, or whether he had ever gone off with the rest, neither knew.

He was the man, however, for an awkward moment, with his sleek and supple tact, and his engaging idiosyncrasies of speech. Oswald Alfred, for one, was easily convinced that the whole concoction of the title, unwittingly suggested by himself, as he was bound to admit, had been all along an elaborate joke at his own expense. Perhaps, however, it was Lord Amyott's laughter that carried most conviction, despite a grim note of its own; but when he really had mounted his bicycle, and disappeared round the bend in the direction of the main gates and the keeper's lodge, the unhappy young man was quickly and quietly informed of the enormity he had committed in speaking of the Jam as such.

"Did you not know," cried Ghum, "that he was in this country incogs? If I should tell him how you have given away, you go same way as last chauffeur without moment's hesitation."

"And what way was that?" asked Oswald Alfred, remembering Lord Amyott's inquiries; but the question made Ghum angrier than anything else.

"Never mind you!" said he. "You know what happens to servants who do not take satisfaction; let him be a warning to you. I will not tell his Highness what you have done. I dare not. It is more than I am worth."

"But is he 'is 'ighness?" demanded the young man. "First you say it's all a cod, and then you talk as if it wasn't."

"Of course it isn't!" the other declared in all solemnity. "He is exactly what I said him; the title is not invention or beastly lie. It is the whole truth, and nothing but the whole, only his Highness want it kept up the sleeve."