The Brigadier in England

The Adventures of Etienne Gerard: VI. - The Brigadier in England is a short story written by Arthur Conan Doyle first published in The Strand Magazine in march 1903. 15th story of the Gerard saga.

Editions

- in The Strand Magazine (march 1903 [UK]) as The Brigadier in England, 8 ill. by William B. Wollen

- in The Strand Magazine (april 1903 [US])

- in (The) Adventures of Gerard (1903) as How the Brigadier Triumphed in England

- in The Seattle Star (17-21 august 1903 [US]) 2 ill. by Charles N. Landon

- in Les Aventures du brigadier Gérard (september 1922, Albin Michel Collection des maîtres de la littérature étrangère [FR]) as Comment le Brigadier triompha en Angleterre

- in Les Aventures du brigadier Gérard (april 1932, Albin Michel Super Collection [FR]) as Comment le Brigadier triompha en Angleterre

- in Les Aventures du brigadier Gérard (july 1932, Albin Michel à 6 fr. [FR]) as Comment le Brigadier triompha en Angleterre

Illustrations

- Illustrations by William B. Wollen in The Strand Magazine (march 1903)

-

"Holding me with one hand he struck me with the other."

-

"He did it a-purpose! Again and again he said it."

-

"'Time!' said he."

-

"The next instant I saw the pursuer."

-

"'Halloa! It's the frenchman, is it?' said he."

-

"His bullet would have blown out my brains had I been erect."

-

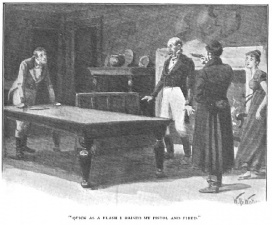

"Quick as a flash I raised my pistol and fired."

-

"Lord Dacre stepped forward and wrung me by the hand."

- Illustrations by Charles N. Landon in The Seattle Star (17 & 21 august 1903)

-

-

"His bullet would have blown out my brains had I been erect."

The Brigadier in England

I have told you, my friends, how I triumphed over the English at the fox- hunt when I pursued the animal so fiercely that even the herd of trained dogs was unable to keep up, and alone with my own hand I put him to the sword. Perhaps I have said too much of the matter, but there is a thrill in the triumphs of sport which even warfare cannot give, for in warfare you share your successes with your regiment and your army, but in sport it is you yourself unaided who have won the laurels. It is an advantage which the English have over us that in all classes they take great interest in every form of sport. It may be that they are richer than we, or it may be that they are more idle: but I was surprised when I was a prisoner in that country to observe how widespread was this feeling, and how much it filled the minds and the lives of the people. A horse that will run, a cock that will fight, a dog that will kill rats, a man that will box—they would turn away from the Emperor in all his glory in order to look upon any of these.

I could tell you many stories of English sport, for I saw much of it during the time that I was the guest of Lord Rufton, after the order for my exchange had come to England. There were months before I could be sent back to France, and during this time I stayed with this good Lord Rufton at his beautiful house of High Combe, which is at the northern end of Dartmoor. He had ridden with the police when they had pursued me from Princetown, and he had felt toward me when I was overtaken as I would myself have felt had I, in my own country, seen a brave and debonair soldier without a friend to help him. In a word, he took me to his house, clad me, fed me, and treated me as if he had been my brother. I will say this of the English, that they were always generous enemies, and very good people with whom to fight.

In the Peninsula the Spanish outposts would present their muskets at ours, but the British their brandy-flasks. And of all these generous men there was none who was the equal of this admirable milord, who held out so warm a hand to an enemy in distress.

Ah! what thoughts of sport it brings back to me, the very name of High Combe! I can see it now, the long, low brick house, warm and ruddy, with white plaster pillars before the door. He was a great sportsman, this Lord Rufton, and all who were about him were of the same sort. But you will be pleased to hear that there were few things in which I could not hold my own, and in some I excelled. Behind the house was a wood in which pheasants were reared, and it was Lord Rufton's joy to kill these birds, which was done by sending in men to drive them out while he and his friends stood outside and shot them as they passed. For my part, I was more crafty, for I studied the habits of the bird, and stealing out in the evening I was able to kill a number of them as they roosted in the trees. Hardly a single shot was wasted, but the keeper was attracted by the sound of the firing, and he implored me in his rough English fashion to spare those that were left. That night I was able to place twelve birds as a surprise upon Lord Rufton's supper-table, and he laughed until he cried, so overjoyed was he to see them. "Gad, Gerard, you'll be the death of me yet!" he cried. Often he said the same thing, for at every turn I amazed him by the way in which I entered into the sports of the English.

There is a game called cricket which they play in the summer, and this also I learned. Rudd, the head gardener, was a famous player of cricket, and so was Lord Rufton himself. Before the house was a lawn, and here it was that Rudd taught me the game. It is a brave pastime, a game for soldiers, for each tries to strike the other with the ball, and it is but a small stick with which you may ward it off. Three sticks behind show the spot beyond which you may not retreat. I can tell you that it is no game for children, and I will confess that, in spite of my nine campaigns, I felt myself turn pale when first the ball flashed past me. So swift was it that I had not time to raise my stick to ward it off, but by good fortune it missed me and knocked down the wooden pins which marked the boundary. It was for Rudd then to defend himself and for me to attack. When I was a boy in Gascony I learned to throw both far and straight, so that I made sure that I could hit this gallant Englishman.

With a shout I rushed forward and hurled the ball at him. It flew as swift as a bullet toward his ribs, but without a word he swung his staff and the ball rose a surprising distance in the air. Lord Rufton clapped his hands and cheered. Again the ball was brought to me, and again it was for me to throw. This time it flew past his head, and it seemed to me that it was his turn to look pale.

But he was a brave man, this gardener, and again he faced me. Ah, my friends, the hour of my triumph had come! It was a red waistcoat that he wore, and at this I hurled the ball. You would have said that I was a gunner, not a hussar, for never was so straight an aim. With a despairing cry— the cry of the brave man who is beaten—he fell upon the wooden pegs behind him, and they all rolled upon the ground together. He was cruel, this English milord, and he laughed so that he could not come to the aid of his servant. It was for me, the victor, to rush forward to embrace this intrepid player, and to raise him to his feet with words of praise, and encouragement, and hope. He was in pain and could not stand erect, yet the honest fellow confessed that there was no accident in my victory. "He did it a-purpose! He did it a-purpose!"

Again and again he said it. Yes, it is a great game this cricket, and I would gladly have ventured upon it again but Lord Rufton and Rudd said that it was late in the season, and so they would play no more.

How foolish of me, the old, broken man, to dwell upon these successes, and yet I will confess that my age has been very much soothed and comforted by the memory of the women who have loved me and the men whom I have overcome. It is pleasant to think that five years afterward, when Lord Rufton came to Paris after the peace, he was able to assure me that my name was still a famous one in the north of Devonshire for the fine exploits that I had performed. Especially, he said, they still talked over my boxing match with the Honourable Baldock. It came about in this way. Of an evening many sportsmen would assemble at the house of Lord Rufton, where they would drink much wine, make wild bets, and talk of their horses and their foxes. How well I remember those strange creatures. Sir Barrington, Jack Lupton, of Barnstable, Colonel Addison, Johnny Miller, Lord Sadler, and my enemy, the Honourable Baldock. They were of the same stamp all of them, drinkers, madcaps, fighters, gamblers, full of strange caprices and extraordinary whims. Yet they were kindly fellows in their rough fashion, save only this Baldock, a fat man, who prided himself on his skill at the box-fight. It was he who, by his laughter against the French because they were ignorant of sport, caused me to challenge him in the very sport at which he excelled. You will say that it was foolish, my friends, but the decanter had passed many times, and the blood of youth ran hot in my veins. I would fight him, this boaster; I would show him that if we had not skill at least we had courage. Lord Rufton would not allow it. I insisted. The others cheered me on and slapped me on the back. "No, dash it, Baldock, he's our guest," said Rufton. "It's his own doing," the other answered. "Look here, Rufton, they can't hurt each other if they wear the mawleys," cried Lord Sadler. And so it was agreed.

What the mawleys were I did not know, but presently they brought out four great puddings of leather, not unlike a fencing glove, but larger. With these our hands were covered after we had stripped ourselves of our coats and our waistcoats. Then the table, with the glasses and decanters, was pushed into the corner of the room, and behold us; face to face! Lord Sadler sat in the arm-chair with a watch in his open hand. "Time!" said he.

I will confess to you, my friends, that I felt at that moment a tremor such as none of my many duels have ever given me. With sword or pistol I am at home, but here I only understood that I must struggle with this fat Englishman and do what I could, in spite of these great puddings upon my hands, to overcome him. And at the very outset I was disarmed of the best weapon that was left to me. "Mind, Gerard, no kicking!" said Lord Rufton in my ear. I had only a pair of thin dancing slippers, and yet the man was fat, and a few well-directed kicks might have left me the victor. But there is an etiquette just as there is in fencing, and I refrained. I looked at this Englishman and I wondered how I should attack him. His ears were large and prominent. Could I seize them I might drag him to the ground. I rushed in, but I was betrayed by this flabby glove, and twice I lost my hold. He struck me, but I cared little for his blows, and again I seized him by the ear. He fell, and I rolled upon him and thumped his head upon the ground.

How they cheered and laughed, these gallant Englishmen, and how they clapped me on the back!

"Even money on the Frenchman," cried Lord Sadler.

"He fights foul," cried my enemy, rubbing his crimson ears. "He savaged me on the ground."

"You must take your chance of that," said Lord Rufton, coldly.

"Time!" cried Lord Sadler, and once again we advanced to the assault.

He was flushed, and his small eyes were as vicious as those of a bull- dog. There was hatred on his face. For my part I carried myself lightly and gaily. A French gentleman fights but he does not hate. I drew myself up before him, and I bowed as I have done in the duello.

There can be grace and courtesy as well as defiance in a bow; I put all three into this one, with a touch of ridicule in the shrug which accompanied it. It was at this moment that he struck me. The room spun round me. I fell upon my back. But in an instant I was on my feet again and had rushed to a close combat. His ear, his hair, his nose, I seized them each in turn. Once again the mad joy of the battle was in my veins. The old cry of triumph rose to my lips. "Vive l'Empereur!" I yelled as I drove my head into his stomach. He threw his arm round my neck, and holding me with one hand he struck me with the other. I buried my teeth in his arm, and he shouted with pain. "Call him off, Rufton!" he screamed.

"Call him off, man! He's worrying me!" They dragged me away from him. Can I ever forget it?—the laughter, the cheering, the congratulations! Even my enemy bore me no ill-will, for he shook me by the hand. For my part I embraced him on each cheek. Five years afterward I learned from Lord Rufton that my noble bearing upon that evening was still fresh in the memory of my English friends.

It is not, however, of my own exploits in sport that I wish to speak to you to-night, but it is of the Lady Jane Dacre and the strange adventure of which she was the cause. Lady Jane Dacre was Lord Rufton's sister and the lady of his household. I fear that until I came it was lonely for her, since she was a beautiful and refined woman with nothing in common with those who were about her. Indeed, this might be said of many women in the England of those days, for the men were rude and rough and coarse, with boorish habits and few accomplishments, while the women were the most lovely and tender that I have ever known. We became great friends, the Lady Jane and I, for it was not possible for me to drink three bottles of port after dinner like those Devonshire gentlemen, and so I would seek refuge in her drawing-room, where evening after evening she would play the harpsichord and I would sing the songs of my own land. In those peaceful moments I would find a refuge from the misery which filled me, when I reflected that my regiment was left in the front of the enemy without the chief whom they had learned to love and to follow.

Indeed, I could have torn my hair when I read in the English papers of the fine fighting which was going on in Portugal and on the frontiers of Spain, all of which I had missed through my misfortune in falling into the hands of Milord Wellington.

From what I have told you of the Lady Jane you will have guessed what occurred, my friends. Etienne Gerard is thrown into the company of a young and beautiful woman. What must it mean for him? What must it mean for her? It was not for me, the guest, the captive, to make love to the sister of my host. But I was reserved.

I was discreet. I tried to curb my own emotions and to discourage hers. For my own part I fear that I betrayed myself, for the eye becomes more eloquent when the tongue is silent. Every quiver of my fingers as I turned over her music-sheets told her my secret. But she—she was admirable. It is in these matters that women have a genius for deception. If I had not penetrated her secret I should often have thought that she forgot even that I was in the house. For hours she would sit lost in a sweet melancholy, while I admired her pale face and her curls in the lamp-light, and thrilled within me to think that I had moved her so deeply. Then at last I would speak, and she would start in her chair and stare at me with the most admirable pretence of being surprised to find me in the room. Ah! how I longed to hurl myself suddenly at her feet, to kiss her white hand, to assure her that I had surprised her secret and that I would not abuse her confidence.

But no, I was not her equal, and I was under her roof as a castaway enemy. My lips were sealed. I endeavoured to imitate her own wonderful affectation of indifference, but, as you may think? I was eagerly alert for any opportunity of serving her.

One morning Lady Jane had driven in her phaeton to Okehampton, and I strolled along the road which led to that place in the hope that I might meet her on her return.

It was the early winter, and banks of fading fern sloped down to the winding road. It is a bleak place this Dartmoor, wild and rocky—a country of wind and mist.

I felt as I walked that it is no wonder Englishmen should suffer from the spleen. My own heart was heavy within me, and I sat upon a rock by the wayside looking out on the dreary view with my thoughts full of trouble and foreboding. Suddenly, however, as I glanced down the road, I saw a sight which drove everything else from my mind, and caused me to leap to my feet with a cry of astonishment and anger.

Down the curve of the road a phaeton was coming, the pony tearing along at full gallop. Within was the very lady whom I had come to meet. She lashed at the pony like one who endeavours to escape from some pressing danger, glancing ever backward over her shoulder. The bend of the road concealed from me what it was that had alarmed her, and I ran forward not knowing what to expect.

The next instant I saw the pursuer, and my amazement was increased at the sight. It was a gentleman in the red coat of an English fox-hunter, mounted on a great grey horse. He was galloping as if in a race, and the long stride of the splendid creature beneath him soon brought him up to the lady's flying carriage. I saw him stoop and seize the reins of the pony, so as to bring it to a halt. The next instant he was deep in talk with the lady, he bending forward in his saddle and speaking eagerly, she shrinking away from him as if she feared and loathed him.

You may think, my dear friends, that this was not a sight at which I could calmly gaze. How my heart thrilled within me to think that a chance should have been given to me to serve the Lady Jane! I ran—oh, good Lord, how I ran! At last, breathless, speechless, I reached the phaeton. The man glanced up at me with his blue English eyes, but so deep was he in his talk that he paid no heed to me, nor did the lady say a word. She still leaned back, her beautiful pale face gazing up at him. He was a good-looking fellow —tall, and strong, and brown; a pang of jealousy seized me as I looked at him. He was talking low and fast, as the English do when they are in earnest.

"I tell you, Jinny, it's you and only you that I love," said he. "Don't bear malice, Jinny. Let by-gones be by-gones. Come now, say it's all over."

"No, never, George, never!" she cried.

A dusky red suffused his handsome face. The man was furious.

"Why can't you forgive me, Jinny?"

"I can't forget the past."

"By George, you must! I've asked enough. It's time to order now. I'll have my rights, d'ye hear?" His hand closed upon her wrist.

At last my breath had returned to me.

"Madame," I said, as I raised my hat, "do I intrude, or is there any possible way in which I can be of service to you?"

But neither of them minded me any more than if I had been a fly who buzzed between them. Their eyes were locked together.

"I'll have my rights, I tell you. I've waited long enough."

"There's no use bullying, George."

"Do you give in?"

"No, never!"

"Is that your final answer?"

"Yes, it is."

He gave a bitter curse and threw down her hand.

"All right, my lady, we'll see about this."

"Excuse me, sir!" said I, with dignity.

"Oh, go to blazes!" he cried, turning on me with his furious face. The next instant he had spurred his horse and was galloping down the road once more.

Lady Jane gazed after him until he was out of sight, and I was surprised to see that her face wore a smile and not a frown. Then she turned to me and held out her hand.

"You are very kind, Colonel Gerard. You meant well, I am sure."

"Madame," said I, "if you can oblige me with the gentleman's name and address I will arrange that he shall never trouble you again."

"No scandal, I beg of you," she cried.

"Madame, I could not so far forget myself. Rest assured that no lady's name would ever be mentioned by me in the course of such an incident. In bidding me to go to blazes this gentleman has relieved me from the embarrassment of having to invent a cause of quarrel."

"Colonel Gerard," said the lady, earnestly, "you must give me your word as a soldier and a gentleman that this matter goes no farther, and also that you will say nothing to my brother about what you have seen. Promise me!"

"If I must."

"I hold you to your word. Now drive with me to High Combe, and I will explain as we go."

The first words of her explanation went into me like a sabre-point.

"That gentleman," said she, "is my husband."

"Your husband!"

"You must have known that I was married." She seemed surprised at my agitation.

"I did not know."

"This is Lord George Dacre. We have been married two years. There is no need to tell you how he wronged me. I left him and sought a refuge under my brother's roof. Up till to-day he has left me there unmolested.

What I must above all things avoid is the chance of a duel betwixt my husband and my brother. It is horrible to think of. For this reason Lord Rufton must know nothing of this chance meeting of to-day."

"If my pistol could free you from this annoyance—"

"No, no, it is not to be thought of. Remember your promise, Colonel Gerard. And not a word at High Combe of what you have seen!"

Her husband! I had pictured in my mind that she was a young widow. This brown-faced brute with his "go to blazes" was the husband of this tender dove of a woman. Oh, if she would but allow me to free her from so odious an encumbrance! There is no divorce so quick and certain as that which I could give her. But a promise is a promise, and I kept it to the letter. My mouth was sealed.

In a week I was to be sent back from Plymouth to St. Malo, and it seemed to me that I might never hear the sequel of the story. And yet it was destined that it should have a sequel and that I should play a very pleasing and honourable part in it.

It was only three days after the event which I have described when Lord Rufton burst hurriedly into my room.

His face was pale and his manner that of a man in extreme agitation.

"Gerard," he cried, "have you seen Lady Jane Dacre?"

I had seen her after breakfast and it was now mid-day.

"By Heaven, there's villainy here!" cried my poor friend, rushing about like a madman. "The bailiff has been up to say that a chaise and pair were seen driving full split down the Tavistock Road. The blacksmith heard a woman scream as it passed his forge. Jane has disappeared. By the Lord, I believe that she has been kidnapped by this villain Dacre." He rang the bell furiously. "Two horses, this instant!" he cried. "Colonel Gerard, your pistols! Jane comes back with me this night from Gravel Hanger or there will be a new master in High Combe Hall."

Behold us then within half an hour, like two knight-errants of old, riding forth to the rescue of this lady in distress. It was near Tavistock that Lord Dacre lived, and at every house and toll-gate along the road we heard the news of the flying post-chaise in front of us, so there could be no doubt whither they were bound. As we rode Lord Rufton told me of the man whom we were pursuing.

His name, it seems, was a household word throughout all England for every sort of mischief. Wine, women, dice, cards, racing—in all forms of debauchery he had earned for himself a terrible name. He was of an old and noble family, and it had been hoped that he had sowed his wild oats when he married the beautiful Lady Jane Rufton.

For some months he had indeed behaved well, and then he had wounded her feelings in their most tender part by some unworthy liaison. She had fled from his house and taken refuge with her brother, from whose care she had now been dragged once more, against her will. I ask you if two men could have had a fairer errand than that upon which Lord Rufton and myself were riding.

"That's Gravel Hanger," he cried at last, pointing with his crop, and there on the green side of a hill was an old brick and timber building as beautiful as only an English country-house can be. "There's an inn by the park-gate, and there we shall leave our horses," he added.

For my own part it seemed to me that with so just a cause we should have done best to ride boldly up to his door and summon him to surrender the lady. But there I was wrong. For the one thing which every Englishman fears is the law. He makes it himself, and when he has once made it it becomes a terrible tyrant before whom the bravest quails. He will smile at breaking his neck, but he will turn pale at breaking the law. It seems, then, from what Lord Rufton told me as we walked through the park, that we were on the wrong side of the law in this matter. Lord Dacre was in the right in carrying off his wife, since she did indeed belong to him, and our own position now was nothing better than that of burglars and trespassers. It was not for burglars to openly approach the front door. We could take the lady by force or by craft, but we could not take her by right, for the law was against us. This was what my friend explained to me as we crept up toward the shelter of a shrubbery which was close to the windows of the house. Thence we could examine this fortress, see whether we could effect a lodgment in it, and, above all, try to establish some communication with the beautiful prisoner inside.

There we were, then, in the shrubbery, Lord Rufton and I, each with a pistol in the pockets of our riding coats, and with the most resolute determination in our hearts that we should not return without the lady.

Eagerly we scanned every window of the wide-spread house.

Not a sign could we see of the prisoner or of anyone else; but on the gravel drive outside the door were the deep-sunk marks of the wheels of the chaise. There was no doubt that they had arrived. Crouching among the laurel bushes we held a whispered council of wary but a singular interruption brought it to an end.

Out of the door of the house there stepped a tall, flaxen-haired man, such a figure as one would choose for the flank of a Grenadier company. As he turned his brown face and his blue eyes toward us I recognised Lord Dacre.

With long strides he came down the gravel path straight for the spot where we lay.

"Come out, Ned!" he shouted; "you'll have the game-keeper putting a charge of shot into you. Come out, man, and don't skulk behind the bushes."

It was not a very heroic situation for us. My poor friend rose with a crimson face. I sprang to my feet also and bowed with such dignity as I could muster.

"Halloa! it's the Frenchman, is it?" said he, without returning my bow. "I've got a crow to pluck with him already. As to you, Ned, I knew you would be hot on our scent, and so I was looking out for you. I saw you cross the park and go to ground in the shrubbery. Come in, man, and let us have all the cards on the table."

He seemed master of the situation, this handsome giant of a man, standing at his ease on his own ground while we slunk out of our hiding-place. Lord Rufton had said not a word, but I saw by his darkened brow and his sombre eyes that the storm was gathering. Lord Dacre led the way into the house, and we followed close at his heels.

He ushered us himself into an oak-panelled sitting-room, closing the door behind us. Then he looked me up and down with insolent eyes.

"Look here, Ned," said he, "time was when an English family could settle their own affairs in their own way.

What has this foreign fellow got to do with your sister and my wife?"

"Sir," said I, "permit me to point out to you that this is not a case merely of a sister or a wife, but that I am the friend of the lady in question, and that I have the privilege which every gentleman possesses of protecting a woman against brutality. It is only by a gesture that I can show you what I think of you." I had my riding glove in my hand, and I flicked him across the face with it. He drew back with a bitter smile and his eyes were as hard as flint.

"So you've brought your bully with you, Ned?" said he. "You might at least have done your fighting yourself, if it must come to a fight."

"So I will," cried Lord Rufton. "Here and now."

"When I've killed this swaggering Frenchman," said Lord Dacre. He stepped to a side table and opened a brass-bound case. "By Gad," said he, "either that man or I go out of this room feet foremost. I meant well by you, Ned; I did, by George, but I'll shoot this led-captain of yours as sure as my name's George Dacre.

Take your choice of pistols, sir, and shoot across this table. The barkers are loaded. Aim straight and kill me if you can, for by the Lord if you don't, you're done."

In vain Lord Rufton tried to take the quarrel upon himself. Two things were clear in my mind—one that the Lady Jane had feared above all things that her husband and brother should fight, the other that if I could but kill this big milord, then the whole question would be settled forever in the best way. Lord Rufton did not want him. Lady Jane did not want him. Therefore, I, Etienne Gerard, their friend, would pay the debt of gratitude which I owed them by freeing them of this encumbrance. But, indeed, there was no choice in the matter, for Lord Dacre was as eager to put a bullet into me as I could be to do the same service to him. In vain Lord Rufton argued and scolded. The affair must continue.

"Well, if you must fight my guest instead of myself, let it be to-morrow morning with two witnesses," he cried, at last; "this is sheer murder across the table."

"But it suits my humour, Ned," said Lord Dacre.

"And mine, sir," said I.

"Then I'll have nothing to do with it," cried Lord Rufton. "I tell you, George, if you shoot Colonel Gerard under these circumstances you'll find yourself in the dock instead of on the bench. I won't act as second, and that's flat."

"Sir," said I, "I am perfectly prepared to proceed without a second."

"That won't do. It's against the law," cried Lord Dacre. "Come, Ned, don't be a fool. You see we mean to fight. Hang it, man, all I want you to do is to drop a handkerchief."

"I'll take no part in it."

"Then I must find someone who will," said Lord Dacre.

He threw a cloth over the pistols which lay upon the table, and he rang the bell. A footman entered. "Ask Colonel Berkeley if he will step this way. You will find him in the billiard-room."

A moment later there entered a tall thin Englishman with a great moustache, which was a rare thing amid that clean-shaven race. I have heard since that they were worn only by the Guards and the Hussars. This Colonel Berkeley was a guardsman. He seemed a strange, tired, languid, drawling creature with a long black cigar thrusting out, like a pole from a bush, amidst that immense moustache. He looked from one to the other of us with true English phlegm, and he betrayed not the slightest surprise when he was told our intention.

"Quite so," said he; "quite so."

"I refuse to act, Colonel Berkeley," cried Lord Rufton.

"Remember, this duel cannot proceed without you, and I hold you personally responsible for anything that happens."

This Colonel Berkeley appeared to be an authority upon the question, for he removed the cigar from his mouth and he laid down the law in his strange, drawling voice.

"The circumstances are unusual but not irregular, Lord Rufton," said he. "This gentleman has given a blow and this other gentleman has received it. That is a clear issue. Time and conditions depend upon the person who demands satisfaction. Very good. He claims it here and now, across the table. He is acting within his rights. I am prepared to accept the responsibility."

There was nothing more to be said. Lord Rufton sat moodily in the corner with his brows drawn down and his hands thrust deep into the pockets of his riding-breeches.

Colonel Berkeley examined the two pistols and laid them both in the centre of the table. Lord Dacre was at one end and I at the other, with eight feet of shining mahogany between us. On the hearth-rug with his back to the fire, stood the tall colonel, his handkerchief in his left hand, his cigar between two fingers of his right.

"When I drop the handkerchief," said he, "you will pick up your pistols and you will fire at your own convenience.

Are you ready?"

"Yes," we cried.

His hand opened and the handkerchief fell. I bent swiftly forward and seized a pistol, but the table, as I have said, was eight feet across, and it was easier for this long-armed milord to reach the pistols than it was for me.

I had not yet drawn myself straight before he fired, and to this it was that I owe my life. His bullet would have blown out my brains had I been erect. As it was it whistled through my curls. At the same instant, just as I threw up my own pistol to fire, the door flew open and a pair of arms were thrown round me. It was the beautiful, flushed, frantic face of Lady Jane which looked up into mine.

"You sha'n't fire! Colonel Gerard, for my sake don't fire," she cried. "It is a mistake, I tell you, a mistake, a mistake! He is the best and dearest of husbands. Never again shall I leave his side." Her hands slid down my arm and closed upon my pistol.

"Jane, Jane," cried Lord Rufton; "come with me.

You should not be here. Come away."

"It is all confoundedly irregular," said Colonel Berkeley.

"Colonel Gerard, you won't fire, will you? My heart would break if he were hurt."

"Hang it all, Jinny, give the fellow fair play," cried Lord Dacre. "He stood my fire like a man, and I won't see him interfered with. Whatever happens I can't get worse than I deserve."

But already there had passed between me and the lady a quick glance of the eyes which told her everything.

Her hands slipped from my arm. "I leave my husband's life and my own happiness to Colonel Gerard," said she.

How well she knew me, this admirable woman! I stood for an instant irresolute, with the pistol cocked in my hand. My antagonist faced me bravely, with no blenching of his sunburnt face and no flinching of his bold, blue eyes.

"Come, come, sir, take your shot!" cried the colonel from the mat.

"Let us have it, then," said Lord Dacre.

I would, at least, show them how completely his life was at the mercy of my skill. So much I owed to my own self-respect. I glanced round for a mark. The colonel was looking toward my antagonist, expecting to see him drop. His face was sideways to me, his long cigar projecting from his lips with an inch of ash at the end of it.

Quick as a flash I raised my pistol and fired.

"Permit me to trim your ash, sir," said I, and I bowed with a grace which is unknown among these islanders.

I am convinced that the fault lay with the pistol and not with my aim. I could hardly believe my own eyes when I saw that I had snapped off the cigar within half an inch of his lips. He stood staring at me with the ragged stub of the cigar-end sticking out from his singed mustache. I can see him now with his foolish, angry eyes and his long, thin, puzzled face. Then he began to talk. I have always said that the English are not really a phlegmatic or a taciturn nation if you stir them out of their groove. No one could have talked in a more animated way than this colonel. Lady Jane put her hands over her ears.

"Come, come, Colonel Berkeley," said Lord Dacre, sternly, "you forget yourself. There is a lady in the room."

The colonel gave a stiff bow.

"If Lady Dacre will kindly leave the room," said he,

"I will be able to tell this infernal little Frenchman what I think of him and his monkey tricks."

I was splendid at that moment, for I ignored the words that he had said and remembered only the extreme provocation.

"Sir," said I, "I freely offer you my apologies for this unhappy incident. I felt that if I did not discharge my pistol Lord Dacre's honour might feel hurt, and yet it was quite impossible for me, after hearing what this lady has said, to aim it at her husband. I looked round for a mark, therefore, and I had the extreme misfortune to blow your cigar out of your mouth when my intention had merely been to snuff the ash. I was betrayed by my pistol. This is my explanation, sir, and if after listening to my apologies you still feel that I owe you satisfaction, I need not say that it is a request which I am unable to refuse."

It was certainly a charming attitude which I had assumed, and it won the hearts of all of them. Lord Dacre stepped forward and wrung me by the hand. "By George, sir," said he, "I never thought to feel toward a Frenchman as I do to you. You're a man and a gentleman, and I can't say more." Lord Rufton said nothing, but his hand-grip told me all that he thought. Even Colonel Berkeley paid me a compliment, and declared that he would think no more about the unfortunate cigar.

And she — ah, if you could have seen the look she gave me, the flushed cheek, the moist eye, the tremulous lip!

When I think of my beautiful Lady Jane it is at that moment that I recall her. They would have had me stay to dinner, but you will understand, my friends, that this was no time for either Lord Rufton or myself to remain at Gravel Hanger. This reconciled couple desired only to be alone. In the chaise he had persuaded her of his sincere repentance, and once again they were a loving husband and wife. If they were to remain so it was best perhaps that I should go. Why should I unsettle this domestic peace? Even against my own will my mere presence and appearance might have their effect upon the lady. No, no, I must tear myself away—even her persuasions were unable to make me stop. Years afterward I heard that the household of the Dacres was among the happiest in the whole country, and that no cloud had ever come again to darken their lives. Yet I dare say if he could have seen into his wife's mind—but there, I say no more! A lady's secret is her own, and I fear that she and it are buried long years ago in some Devonshire churchyard. Perhaps all that gay circle are gone and the Lady Jane only lives now in the memory of an old half-pay French brigadier. He at least can never forget.