The Retirement of Signor Lambert

The Retirement of Signor Lambert is a short story written by Arthur Conan Doyle first published in Pearson's Magazine in december 1898.

Editions

- in Pearson's Magazine (december 1898 [UK]) 5 illustrations by Hana

- in The Cosmopolitan (december 1898 [US]) 5 ill. by B. West Clinedinst

- in La Merveilleuse découverte de Raffles Haw (ca. 1920-1923, L'Édition Française Illustrée [FR]) as Comment le signor Lambert quitta l'Opéra

Illustrations

- Illustrations by Hana in Pearson's Magazine (december 1898)

-

The Retirement of Signor Lambert

-

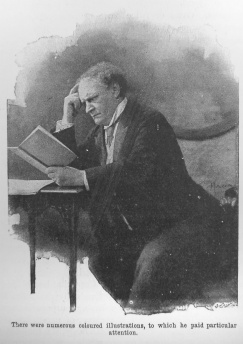

There were numerous illustrations, to which he paid particular aattention.

-

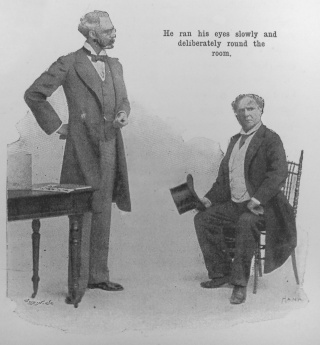

He ran his eyes slowly and deliberatly round the room.

-

He opened his bag, and began to take out all sorts of things.

-

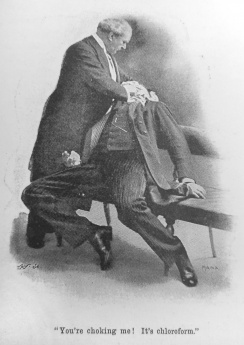

"You're choking me! It's cloroform."

- Illustrations by B. West Clinedinst in The Cosmopolitan (december 1898)

-

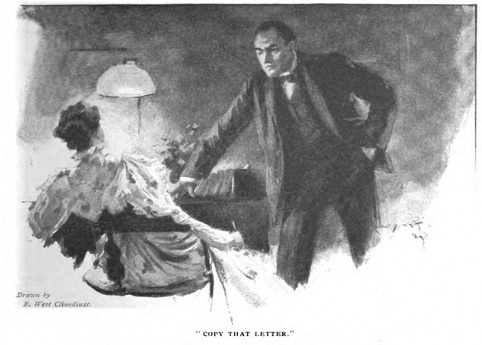

"Copy that letter."

-

"Sir William did not even answer him."

-

"Read and reread the text."

-

"'You, Holden!' he cried, 'You leave my service to-night'"

-

"His head had fallen back and he muttered into the inhaler."

Characters

- Sir William Sparter

- Lady Jacqueline Sparter aka Jacky

- Peterson

- Signor Cecil Lambert

- Mrs. McKay

- Dr. Manifold Ormonde

- Lord Marvin

- Mclntyre

- Holden

- Jean Caravatti

Locations

- Portsmouth Dockyard

- Lake Road, Landport

- Leinster Gardens, Taplow

- 138B, Half Moon street, W.

- Cavendish square

Towns

Regions

Plot summary (spoiler)

Sir William Sparter is a self-made man, a dockyard fitter who became a rich proprietor. He married a beautiful woman but he never succeeded too be loved by her. One day, he discovers that his wife had passion for another man, signor Cecil Lambert, an Opera tenor. He forces her to write a letter to Lambert asking him for a rendez-vous at a specific address. Before sending the letter, Sparter studies books of anatomy of the larynx. He also asks several questions to a doctor about cutting vocal cords. Then Sparter meets Lambert at the rendez-vous in an isolated artist studio. He tells him he wants to change his voice. He catches him, applies chloroform on his nose and does some surgery on the singer's throat. The voice of the singer has so changed that even his servant didn't recognized his master's voice. He had to definitively retire from Opera.

The Retirement of Signor Lambert

Sir William Sparter was a man who had raised himself in the course of a quarter of a century from earning four-and-twenty shillings a week as a fitter in Portsmouth Dockyard to being the owner of a yard and a fleet of his own. The little house in Lake Road, Landport, where he, an obscure mechanic, had first conceived the idea of the boilers which are associated with his name, is still pointed out to the curious. But now, at the age of fifty, he owned a mansion in Leinster Gardens, a country house at Taplow and a shooting in Argyleshire, with the best stable, the choicest cellars and the prettiest wife in town.

As untiring and inflexible as one of his own engines, his life had been directed to the one purpose of attaining the very best which the world had to give. Square-headed and round-shouldered, with massive, clean-shaven face and slow, deep-set eyes, he was the very embodiment of persistency and strength. Never once from the beginning of his career had public failure of any sort tarnished its brilliancy.

And yet he had failed in one thing, and that the most important of all. He had never succeeded in gaining the affection of his wife. She was the daughter of a surgeon, and the belle of a northern town when he married her. Even then he was rich and powerful, which made her overlook the twenty years which divided them. But he had come on a long way since then. His great Brazilian contract, his conversion into a company, his baronetcy — all these had been since his marriage. Only in the one thing he had never progressed. He could frighten his wife, he could dominate her, he could make her admire his strength and respect his consistency, he could mold her to his will in every other direction, but, do what he would, he could not make her love him.

But it was not for want of trying. With the unrelaxing patience which made him great in business, he had striven, year in and year out, to win her affection. But the very qualities which had helped him in his public life had made him unbearable in private. He was tactless, unsympathetic, overbearing, almost brutal sometimes, and utterly unable to think out those small attentions in word and deed which women value far more than the larger material benefits. The hundred-pound check tossed across a breakfast table is a much smaller thing to a woman than the five-shilling charm which represents some thought and some trouble upon the part of the giver.

Sparter failed to understand this. With his mind full of the affairs of his firm, he had little time for the delicacies of life, and he endeavored to atone by periodical munificence. At the end of five years he found that he had lost rather than gained in the lady's affections. Then, at this unwonted sense of failure, the evil side of the man's nature began to stir, and he became dangerous. But he was more dangerous still when a letter of his wife's came, through the treachery of a servant, into his hands, and he realized that if she was cold to him she had passion enough for another. His firm, his ironclads, his patents, everything was dropped, and he turned his huge energies to the undoing of the man.

He had been cold and silent during dinner that evening, and she had wondered vaguely what had occurred to change him. He had said nothing while they sat together over their coffee in the drawing-room. Once or twice she had glanced at him in surprise, and had found those deep-set gray eyes fixed upon her with an expression that was new to her. Her mind had been full of some one else, but gradually her husband's silence and the inscrutable expression of his face forced themselves upon her attention.

"You don't seem yourself, to-night, William. What is the matter?" she asked. "I hope there has been nothing to trouble you."

He was still silent and leaned back in his arm-chair, watching her beautiful face, which had turned pale with the sense of some impending catastrophe.

"Can I do anything for you, William?"

"Yes, you can write a letter."

"What is the letter?"

"I will tell you presently."

The last murmur died away in the house, and they heard the discreet step of Peterson, the butler, and the snick of the lock as he made all secure for the night. Sir William Sparter sat listening for a while. Then he rose.

"Come into my study," said he.

The room was dark, but he switched on the green-shaded electric lamp which stood upon the writing-table.

"Sit there at the table," said he. He closed the door and seated himself beside her. "I only wanted to tell you, Jacky, that I know about Lambert."

She gasped and shivered, flinching away from him with her hands out as if she feared a blow.

"Yes, I know everything," said he, and his quiet tone carried such conviction with it that she could not question what he said. She made no reply, but sat with her eyes fixed upon his grave, massive face. A clock ticked loudly upon the mantelpiece, but everything else was silent in the house. She had never noticed that ticking before, but now it was like the hammering of a nail into her head. He rose and put a sheet of paper before her. Then he drew one from his own pocket and flattened it out upon the corner of the table.

"I have a rough draft here of the letter which I wish you to copy," said he. "I will read it to you if you like. 'My own dearest Cecil: I will be at No. 29 at half-past six, and I particularly wish you to come before you go down to the opera. Don't fail me, for I have the very strongest reasons for wishing to see you. Ever yours, Jacqueline.' Take up a pen and copy that letter."

"William, you are plotting some revenge. Oh, William, if I have wronged you, I am so sorry—"

"Copy that letter!"

"But what is it that you wish to do? Why should you desire him to come at that hour?"

"Copy that letter!"

"How can you be so harsh, William? You know very well—"

"Copy that letter!"

"I begin to hate you, William. I believe that it is a fiend, not a man, that I have married."

"Copy that letter!"

Gradually the inflexible will and the unfaltering purpose began to prevail over the creature of nerves and moods. Reluctantly, mutinously, she took the pen in her hand.

"You wouldn't harm him, William!"

"Copy that letter!"

"Will you promise to forgive me, if I do?"

"Copy that letter!"

She looked at him with the intention of defying him, but those masterful gray eyes dominated her. She was like a half-hypnotized creature, resentful, and yet obedient.

"There, will that satisfy you?"

He took the note from her hand and placed it in an envelope.

"Now address it to him!"

She wrote "Cecil Lambert, Esq., 138B, Half Moon street, W." in a straggling, agitated hand. Her husband very deliberately blotted it and placed it carefully in his pocket-book.

"I hope that you are satisfied now." said she with weak petulance.

"Quite," said he gravely. "You can go to your room. Mrs. McKay has my orders to sleep with you, and to see that you write no letters."

"Mrs. McKay! Do you expose me to the humiliation of being watched by my own servants?"

"Go to your room!"

"If you imagine that I am going to be under the orders of the housekeeper—"

"Go to your room!"

"Oh. William, who would have thought in the old days that you could ever have treated me like this? If my mother had ever dreamed—"

He took her by the arm, and led her to the door.

"Go to your room!" said he, and she passed out into the darkened hall. He closed the door and returned to the writing table. Out of a drawer he took two things which he had purchased that day, the one a paper and the other a book. The former was a recent number of the "Musical Record," and it contained a biography and picture of the famous Signor Lambert, whose wonderful tenor voice had been the delight of the public and the despair of his rivals. The picture was that of a good-natured, self-satisfied creature, young and handsome, with a full eye, a curling mustache and a bull neck. The biography explained that he was only in his twenty-seventh year, that his career had been one continued triumph, that he was devoted to his art, and that his voice was worth to him, at a very moderate computation, some twenty thousand pounds a year. All this Sir William Sparter read very carefully, with his great brows drawn down, and a furrow like a gash between them, as his way was when his attention was concentrated. Then he folded the paper up again, and he opened the book.

It was a curious work for such a man to select for his reading—a technical treatise upon the organs of speech and voice-production. There were numerous colored illustrations, to which he paid particular attention. Most of them were of the internal anatomy of the larynx, with the silvery vocal cords shining from under the pink arytenoid cartilage. Far into the night Sir William Sparter, with those great virile eyebrows still bunched together, pored over these irrelevant pictures, and read and reread the text in which they were explained.

- * * * *

Dr. Manifold Ormonde, the famous throat specialist, of Cavendish square, was surprised next morning when his butler brought the card of Sir William Sparter into his consulting-room. He had met him at dinner at the table of Lord Marvin a few nights before, and it struck him at that time that he had seldom seen a man who looked such a type of rude, physical health. So he thought again, as the square, thick-set figure of the shipbuilder was ushered in to him.

"Glad to see you again. Sir William," said the specialist. "I hope there is nothing wrong with your health."

"Nothing, thank you."

He sat down in the chair which the doctor had indicated, and he ran his eyes slowly and deliberately round the room. Dr. Ormonde watched him with some curiosity, for he had the air of a man who looks for something which he had expected to see.

"No, I didn't come about my health." said he at last. "I came for information."

"Whatever I can give you is entirely at your disposal."

"I have been studying the throat a little of late. I read Mclntyre's book about it. I suppose that is all right."

"An elementary treatise, but accurate as far as it goes."

"I had an idea that you would be likely to have a model or something of that kind."

For answer the doctor unclasped the lid of a yellow, shining box upon his consulting-room table, and turned it back upon the hinge. Within was a complete model of the human vocal organs.

"You are right, you see," said he.

Sir William Sparter stood up, and bent over the model.

"It's a neat little bit of work," said he, looking at it with the critical eyes of an engineer. "This is the glottis, is it not? And here is the epiglottis."

"Precisely. And here are the cords."

"What would happen if you cut them?"

"Cut what?"

"These things—the vocal cords."

"But you could not cut them. They are out of the reach of accident."

"But if such a thing did happen?"

"There is no such case upon record, but, of course, the person would become dumb—for a time, at any rate."

"You have a large practice among singers, have you not?"

"The largest in London."

"I suppose you agree with what this man Mclntyre says, that a fine voice depends partly upon the cords."

"The volume of sound would depend upon the lung capacity, but the clearness of the note would correspond with the complete control which the singer exercised over the cords.

"Any roughness or notching of the cords would ruin the voice?"

"For singing purposes, undoubtedly—but your researches seem to be taking a very curious direction."

"Yes," said Sir William, as he picked up his hat, and laid a fee upon the corner of the table. "They are a little out of the common, are they not?"

Warburton street is one of the network of thoroughfares which connects Chelsea with Kensington, and it is chiefly remarkable for the number of studios it contains. Signor Lambert, the famous tenor, owned an apartment here, and his neat little dark-green brougham might have been seen several times a week waiting at the head of the long passage which led down to the chambers in question.

When Sir William Sparter, muffled in his overcoat, and carrying a small black leather bag in his hand, turned the corner, he saw the lamps of the carriage against the curb, and knew that the man whom he had come to see was already in the place of assignation. He passed the empty brougham, and walked up the tile-paved passage with the yellow gas lamp shining at the far end of it.

The door was open, and led into a large empty hall, laid down with coconut matting and stained with many footmarks. The place was a rabbit warren by daylight, but now, when the working hours were over, it was deserted. A housekeeper in the basement was the only permanent resident. Sir William paused, but everything was silent, and everything was dark save for one door which was outlined in thin yellow slashes. He pushed it open and entered. Then he locked it upon the inside and put the key in his pocket.

It was a large room, scantily furnished, and lit by a single oil lamp upon a center-table. On a chair at the farther side of the table a man had been sitting, who had sprung to his feet with an exclamation of joy, which had changed into one of surprise, and culminated in an oath.

"What the devil do you mean by locking that door? Unlock it again, sir, this instant!"

Sir William did not even answer him. He advanced to the table, opened the bag, and began to take out all sorts of things—a green bottle, a dentist's gag, an inhaler, a forceps, a curved bistoury, a curious pair of scissors. Signor Lambert stood staring at him in a paralysis of rage and astonishment.

"You infernal scoundrel—who are you, and what do you want?"

Sir William had emptied his bag, and now he took off his overcoat and laid it over the back of a chair. Then for the first time he turned his eyes upon the singer. He was a taller man than himself, but far slighter and weaker. The engineer, though short, was exceedingly powerful, with muscles which had been toughened by hard physical work. His broad shoulders, arching chest and great gnarled hands gave him the outline of a gorilla. Lambert shrunk away from him, frightened by his sinister figure and by his cold, inexorable eyes.

"Have you come to rob me?" he gasped.

"I have come to speak to you. My name is Sparter."

Lambert tried to retain his grasp upon the self-possession which was rapidly slipping away from him.

"Sparter!" said he. with an attempt at jauntiness. "Sir William Sparter, I presume? I have had the pleasure of meeting Lady Sparter, and I have heard her mention you. May I ask the object of this visit?" He buttoned up his coat with twitching fingers, and tried to look rierce over his collar.

"I've come," said Sparter. jerking some fluid from the green bottle into the inhaler, "to change your voice."

"To change my voice?"

"Precisely."

"You are a madman! What do you mean?"

"Kindly lie back upon the settee."

"You are raving! I see it all. You wish to bully me. You have some motive in this. You imagine that there are relations between Lady Sparter and me. I do assure you that your wife—"

"My wife has nothing to do with the matter either now or hereafter. Her name does not appear at all. My motives are musical—purely musical, you understand. I don't like your voice. It wants treatment. Lie back upon the settee!",

"Sir William, I give you my word of honor—"

"Lie back."

"You're choking me! It's chloroform! Help, help, help! You brute! Let me go! Let me go, I say! Oh, please! Lemme—Lemme—Lem—!" His head had fallen back, and he muttered into the inhaler. Sir William pulled up the table which held the lamp and the instrument.

It was some minutes after the gentleman with the overcoat and the bag had emerged that the coachman outside heard a voice shouting, and shouting very hoarsely and angrily, within the building. Presently came the sounds of unsteady steps, and his master, crimson with rage, stumbled out into the yellow circle thrown by the carriage lamps.

"You, Holden!" he cried, "you leave my service to-night. Did you not hear me calling? Why did you not come?"

The man looked at him in bewilderment, and shuddered at the color of his shirt-front.

"Yes. sir, I heard some one calling," he answered, "but it wasn't you, sir. It was a voice that I had never heard before."

"Considerable disappointment was caused at the opera last week," said one of the best-informed musical critics, "by the fact that Signor Cecil Lambert was unable to appear in the various roles which had been announced. On Tuesday night it was only, at the very last instant that the management learned of the grave indisposition which had overtaken him, and had it not been for the presence of Jean Caravatti. who had understudied the part, the piece must have been abandoned. Since then we regret to hear that Signor Lambert's seizure was even more severe than was originally thought, and that it consists of an acute form of laryngitis, spreading to the vocal cords, and involving changes which may permanently affect the quality of his voice. All lovers of music will hope that these reports may prove to be pessimistic, and that we may soon be charmed once more by the finest tenor which we have heard for many a year upon the London operatic stage."